Place Attachment Impacts Meaning in Life

University of Florida. August 09, 2023.

In The Lion King, after the young lion Simba is banished by his evil uncle Scar, he eventually feels compelled to return to a place that offered him comfort and safety—Pride Rock. In The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Walter is constantly “zoning out” to take mental adventures to places where he can explore new experiences, grow, and become interesting and successful. What connects each of these characters is the way their attachment to places seem to drive their sense of meaning in life. For each character, being in certain places sure seems like it fosters a sense that everything is connected, a feeling that life has significance, and a sense that life has a purpose or goal—a greater meaning.

But is place attachment really related to meaning in life? My colleagues and I designed two studies with the support of an ISSEP Seed Grant to learn more, which has now developed into a package of several studies exploring the relationship between place attachment and meaning in life.

The power of place attachment: Safe havens, secure bases… and meaning in life?

First, we considered why people develop attachments to places. Like Simba and Walter Mitty, people naturally gravitate toward places that hold personal significance. But it’s interesting to think about what that really means. It turns out that people become attached to particular places that facilitate a sense of security and give people the courage to explore the world (Scannell & Gifford, 2017b). For example, many of us become attached to our homes, largely because our homes function as safe havens that offer solace and protection from the challenges of everyday life and as secure bases from which we can prepare to go out into the world (Manzo, 2003; Gustafson, 2001).

Second, we considered whether place attachment might reasonably facilitate a sense of meaning in life. Obviously, the physical world is made up of a myriad of places, but not all places are the same. Sociologists typically consider that our home is our “first place,” our workplace is our “second place,” and everything beyond that (e.g., coffee shops, hair salons, city parks) are so-called "third places." Heideggerian philosophy has given rise to a phenomenological approach which assumes that each place has—for each individual—an essence that gives each place a unique character (Lewicka, 2019; Seamon, 1980; Tuan, 1977).

Clockwise from top left: Home, work, and a cafe/bar—examples of what sociologists consider our first, second, and third places.

Of course, most places in the world hardly feature prominently, if at all, in our lives. But when we do become attached to a place’s unique character, it seems to be places that facilitate or reflect our cultures and morals (Cohen, Nisbett, Bowdle, & Schwarz, 1996) such that they become “centers of meaning constructed out of lived experience” (Tuan, 1977). Thus, the places we become attached to also seem to contribute to a sense of community and significance, identity and self-exploration, and meaning (Oldenburg, 1989). Indeed, some prior research suggests that a sense of rootedness and belonging to a place can be associated with a profound feeling that the world makes sense, that one has purpose, and that one is significant—in other words, a profound sense of meaning in life (Baldwin & Keefer, 2020; Wójcik & Tobiasz-Lis, 2021).

Thus, we hypothesized that when people go to, or even simply think about, the places to which they’re attached they’ll feel a heightened sense of meaning in life. To test that hypothesis, we conducted a trio of empirical studies using a variety of methods. Our first study used an experimental design, the second study employed an experience sampling longitudinal design, and the third study used a rigorous pre-post experimental design.

Our research on place attachment and meaning in life

In our first study, using experimental design, 200 participants were randomly assigned to either a “Control place” group or a “Attachment place” group. Participants in the Control place group were asked to think about and describe a place in their current life that was familiar to them but evoked neutral feelings. Participants in the Attachment place group were asked to think about and describe a place they were strongly attached to.

Figure 1. The data patterns from the meta-analysis across Study 1 and its replication study.

Participants in both groups then completed a set of questionnaires measuring a variety of aspects of meaning in life: coherence, purpose, and significance/mattering, as well as the overall presence-of and search-for meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006; Costin & Vignoles, 2020). Some example questions are “I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful” and “I am searching for meaning in my life,” and each question was measured using a numeric scale (e.g., 1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree).

The data patterns revealed that, compared to thinking about neutral places, thinking about places of attachment led people to feel like the world made sense (coherence), to feel like they had goals in their life (purpose), and to feel a greater presence of meaning in life in those places. It was not associated with a more active sense of significance, whereas those participants did more often report desiring or searching for meaning in life.

In a replication study, with 274 university students, most of the effects were replicated. However, we found that participants who thought about a place of attachment led to higher feelings of significance, coherence, and meaning in life (presence and search), but not purpose. To investigate whether the conflicting results of significance and purpose might have reflected relatively lower power to detect their relatively smaller effect sizes (compared to those on meaning in life and coherence), we conducted an internal meta-analysis across both studies to generate a more precise estimate of the effect of experimental condition on each dependent variable. When both studies were aggregated, all dependent variables were significantly higher in the Attachment condition.

In our second study, we used an experience sampling longitudinal design to study whether being physically present in vs. absent from their attachment places is associated with participants’ sense of meaning in life. Every day for 1 week, 348 participants reported their current location, rated their attachment to that place, and rated their perceived level of meaning in life. The results indicated a similar data pattern as the prior studies: when participants were in places they felt attached to, they reported feeling like the world made sense (coherence), like they mattered (significance), and they felt a greater presence of meaning in life. However, they didn’t feel an elevated sense of purpose.

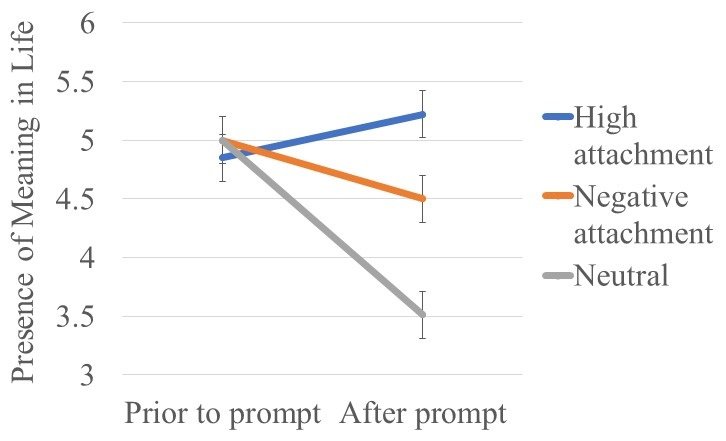

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means of presence of meaning across timepoints for participants in the High Attachment, Neutral, and Negative Attachment conditions.

In a third study, we recruited 472 undergraduate participants in a pre-post design. Participants first answered pre-measures regarding their current meaning in life. Then, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: those in the Neutral condition were asked to choose a place that they have neutral feelings about; those in the High Attachment condition were asked to choose a place they have a strong attachment to; and those in the Negative Attachment condition were asked to choose a place they have a negative attachment to. After the manipulation, participants rated the presence of meaning in life, in the context of the place they wrote about (e.g., “When I am in this place, I understand my life's meaning”). We found that, when accounting for pre-manipulation meaning levels, thinking about High Attachment places increased meaning compared to the Neutral and Negative Attachment conditions.

Place Attachment and Meaning: Different effects on coherence, significance, and purpose

Across these three studies, my colleagues and I found that when participants thought about and were actually present in the places to which they were attached they reported a stronger sense of meaning in life in those places—in particular, a stronger sense of coherence and significance. However, some discrepancies were present regarding whether or not place attachment was associated with a stronger sense of purpose.

Given that pattern, it may be worth noting that Study 1 asked participants to think about a place of attachment, and Study 2 most often collected data while participants were in their homes (53.5% of the time). Thus, these data patterns may suggest that attachment to our “first place” (our home) might primarily serve as a comforting safe-haven/secure-base, where the world makes sense and one feels like one matters, rather than serving as an active arena where one engages in purpose-filled goal pursuit. Thus, one interesting area for future research would be to investigate whether people feel a sense of purpose when they leave their special places to go “out” into the world.

Place attachments bolster meaning—and even broader well-being

People can experience meaning and broader well-being when in their special places, such as (clockwise from top left) the backyard BBQ patio, the home living room or den, the school classroom, and/or the basketball court at the park.

In addition to bolstering meaning, people’s attachment to significant places can facilitate their overall well-being. Experimental evidence found participants who visualized a place they were attached to reported increased feelings of meaning as well as belonging and self-esteem (Scannell & Gifford, 2017a), which is consistent with our finding that it facilitated a meaningful sense of coherent interconnections and personal significance.

Numerous other studies have also found that feeling rooted in particular neighborhoods and rural communities is associated with greater life satisfaction, stronger social ties, and increased trust in others (Cattell et al., 2008; Lewicka, 2011). Indeed, people often identify their neighborhoods and a strong sense of community as sources of solace and rejuvenation (Riger & Lavrakas, 1981; Thurber, 2019) and a source of social capital (Kasarda & Janowitz, 1974). Perhaps as a result, such attachments are correlated with better health and lower depression and anxiety among community samples (Theodori, 2009).

Your special place: A den of coherence and significance, a platform for purpose

Are people’s special places a source of meaning in their lives? Our research, using a variety of methods, suggests they are. People become attached to special places, like one’s home, because such places are safe havens that offer comfort and refuge from the challenges of everyday life, and—as our work illustrates—a place where people can feel a meaningful sense of coherence and a sense of personal significance. Such special places might also serve as secure bases, where one is not necessarily actively engaging in purpose-filled goal pursuit but from which one can prepare to go out into the world. This mixture of places fostering both a sense of being safe havens and secure bases seems to serve existential functions and may be an important component in better understanding how people unlock their immense potential for both well-being and personal growth!

Ashley Krause is a doctoral student researcher at the Florida Social Cognition and Emotion Lab. She received her undergraduate degree in Psychology from Francis Marion University in 2020. Her research interests are mainly regarding the psychology of place and well-being. She takes a socioecological approach to this by understanding how people feel connected to their physical surroundings and, in turn, how those physical surroundings impact people. Her research thus far has studied how places of attachment afford meaning in life.