The Working Self-Concept and Authenticity

By Serena Chen

University of California, Berkeley. April 30, 2024.

Be yourself. Always be true to yourself. The real me. Stay true to yourself. Phrases like these are heard frequently enough that we often don’t think about them too deeply. But when you do stop and think about it, they present a bit of a paradox. When we tell someone to be true to themselves, this implies they have a single, monolithic self, as if we are all more or less the same person across different settings, time, relationships, and so forth.

But when you ask people to describe who they are, say, at work with their supervisor versus on the pickleball court with their buddies, or who they are with a new romantic interest versus a childhood best friend, it becomes readily apparent that people have multiple selves.

Which one of these selves should people aim to be true or authentic to? My research tackles this question by examining the role of the working self-concept in the experience of authenticity.

The “Working” Self-Concept

When Markus and Wurf (1987) first introduced the notion of the working self-concept, they defined it as the subset of a person’s overall constellation of self-knowledge that is brought to mind in the current context (e.g., a classroom). When this happens, the person’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors shift to reflect the specific working self (e.g., one’s student self). The “working” part of the term refers to working or short-term memory. To use the language of a sub-field in psychology known as social cognition, the working self-concept is composed of the particular pieces of self-knowledge, typically stored in long-term memory, that have been temporarily recruited into short-term memory, shaping who the self is in the moment. The content of working memory, including whatever self-knowledge has been brought in, is ever-changing and depends on internal and external cues and circumstances (e.g., the situation a person is in, the people who are around).

Now, when the working self-concept shifts, so too does a person’s subjective experience of the self. This means that even as the overall universe of self-knowledge in a person’s long-term memory is relatively stable, which gives people a sense of stability and continuity in who they are, there is malleability in how people subjectively experience the self. In short, people have multiple, context-specific selves, with different selves at play at different times and in different contexts.

Viewing State Authenticity through the Lens of the Working Self-Concept

If the self is multifaceted and shifts across time and contexts, this implies that a full understanding of what it means to “be authentic” requires taking into account the current context and the particular “self” that is at play in it. In other words, the experience of authenticity, like the self-concept, should vary across time and contexts. Research shows that this is indeed the case and researchers have called this “state authenticity.”

State authenticity refers to people’s current, in-the-moment, feelings about how authentic they are. State authenticity can be understood in contrast to dispositional authenticity, which refers to relatively stable individual differences in authenticity across people (i.e., some people are higher or lower in their general level of authenticity). The past decade or so has seen a sharp jump in research on state authenticity (e.g., Fleeson & Wilt, 2010; Sedikides, Slabu, Lenton, & Thomaes, 2017; Wilt, 2023) – which reflects a growing recognition that the experience of authenticity varies within individuals across time and place just as much (if not more so) than feelings of authenticity differs across individuals at the dispositional level (e.g., Lenton, Bruder, Slabu, & Sedikides, 2013).

The working self-concept approach I have taken in my work provides a direct answer to the question of exactly what “self” one is being true or authentic to when they feel authentic – namely, the working self. Let me provide a few illustrative examples of how we have studied this scientifically.

Relational Selves and Authenticity

Relational selves refer to who we are in our relationships with significant others, be they romantic partners, friends, siblings, or work colleagues (Andersen & Chen, 2002; Chen, Boucher, & Kraus, 2011; Chen et al., 2006). So, a person might possess a distinct relational self with her dad, sister, and college bestie. The construct of relational selves adheres closely to the working self-concept, but focuses on the relational self-knowledge that is brought into working memory in a given context, such as when a person’s talking to their mother on the phone or having date night with their spouse.

Corresponding relational selves should get activated when we are actually interacting with significant others themselves (e.g., my “mother” relational self should be in play when I’m out shopping with my daughter), but relational self-knowledge can come to characterize the working self-concept whenever a significant other is brought to mind—even when the person is not right there in front of you. For example, just thinking about a significant other (e.g., shopping for a gift for the person) or interacting with someone who somehow reminds us of a significant other (e.g., has the same laugh, wears the same perfume) can activate the relevant relational self. However a significant other is brought to mind, research shows that the nature of the working self-concept shifts to reflect the relevant relational self (e.g., Hinkley & Andersen, 1996).

So, what are the implications of relational-self shifts in the working self-concept for authenticity? There are numerous possibilities—let’s take a look at a couple of examples. The first addresses a rather basic question: what relational self-conceptions contribute most to how authentic we feel in our relationships? More pointedly, do I feel more authentic in my relationship with, say, my romantic partner, when my relational self with this partner overlaps a lot with who I am in general (referred to as the “actual” self)? Or, perhaps, do I feel more authentic with my partner when my relational self with them resembles my “ideal” self—that is, the self that I’m hoping and striving to become?

Gan and Chen (2017) sought to answer this very question across a series of studies. In one of them, we first had participants identify a significant other in their lives. Then, we asked them to spend several minutes thinking about how the person they are in their relationship with the person (i.e., the relevant relational self) is either similar to or different from either their actual self (i.e., who they are in general) or their ideal self (i.e., who they aspire to be). In other words, we momentarily led participants to experience a little or a lot of overlap between their relational self and either their actual self or ideal self. Afterward, all participants reported on how authentic they felt in their relationship with their significant other. Which kind of overlap was linked to higher feelings of relational authenticity

Data from Gan and Chen (2017) show that participants felt higher relational authenticity when they thought about ways their relational self overlapped with their actual or ideal self.

Overall, as depicted in the graph, participants reported higher relational authenticity when they were nudged to think about ways in which their relational self overlapped with both their actual self or ideal self relative to when they were asked to think about how their relational self differed from either of these selves. But looking more closely, how much the relational self overlapped with the actual self – a little or a lot – didn’t really make much of a difference in relational authenticity (i.e., the two bars on the right are pretty similar). In contrast, how much the relational self overlapped with participants’ ideal selves did matter (i.e., the two bars on the left are quite different). Specifically, when participants thought about how their relational self overlapped very little with their ideal self, their reports of relational authenticity dropped substantially. In sum, findings like these suggest that feeling authentic in one’s relationships hinges particularly strongly on the degree to which the selves we experience in our relationships approximate our ideal self.

To give a second and very different example of potential implications of relational selves for authenticity, in recent work we have found that people’s perceptions of the state authenticity of their romantic partners during interactions with them are specific to the relational context, rather than being based on people’s perceptions of the dispositional level of authenticity of their partner (Castro, Chen, Ocampo, Gordon, Impett, & Weisbuch, under review). That is, these context-specific perceptions align more with partners’ own ratings of their state authenticity than with partners’ dispositional authenticity scores. The upshot here, then, is that people judge the state authenticity of their romantic partners’ relational selves in context, revealing that the subjective experience – as well as perceptions of others’ state authenticity – depend on the current context and the particular relational self that is activated.

High- and Low-Power Selves and Authenticity

One’s position in a social hierarchy – that is, a position of relatively high or low social power – is another kind of context that can elicit shifts in the working self-concept and therefore should have implications for state authenticity. Social power refers to having influence and control over others’ outcomes (Emerson, 1962; Fiske, 1993; Kipnis, 1972; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959). This control comes from one’s ability to grant or withhold valued resources as well as to dole out punishments (e.g., Keltner, Gruenfeld, & Anderson, 2003). Research has shown that experiencing high versus low power can affect how people think, feel, and act in systematically distinct ways (for reviews, see Galinsky, Rucker, & Magee, 2015; Guinote & Chen, 2018). In my work I’ve been interested in how power affects the working self-concept and, in turn, how authentic people feel.

First off, there’s quite a bit of research suggesting that experiencing high power, in comparison to low power, leads people to be more likely to outwardly express opinions and behaviors that are consistent with their inner traits, beliefs, emotions, and values. To give a few concrete examples, studies have shown that people are more inclined to outwardly express their true attitudes on social issues (e.g., Anderson & Berdhal, 2002), their chronic orientation toward interpersonal relationships (e.g., Chen, Lee-Chai, & Bargh, 2001), and their momentary emotional states (e.g., Hecht & LaFrance, 1998) when experiencing higher (vs. lower) power.

To put it more plainly, having power allows people to “be themselves” more than when lacking power—such as a boss being more likely to say what’s on her mind than her subordinate is. In the language of the working self-concept, the “high-power” self has relatively high internal-external consistency, whereas the “low-power” self has less so. The higher internal-external consistency that comes with higher versus lower power should have implications for how authentic people feel.

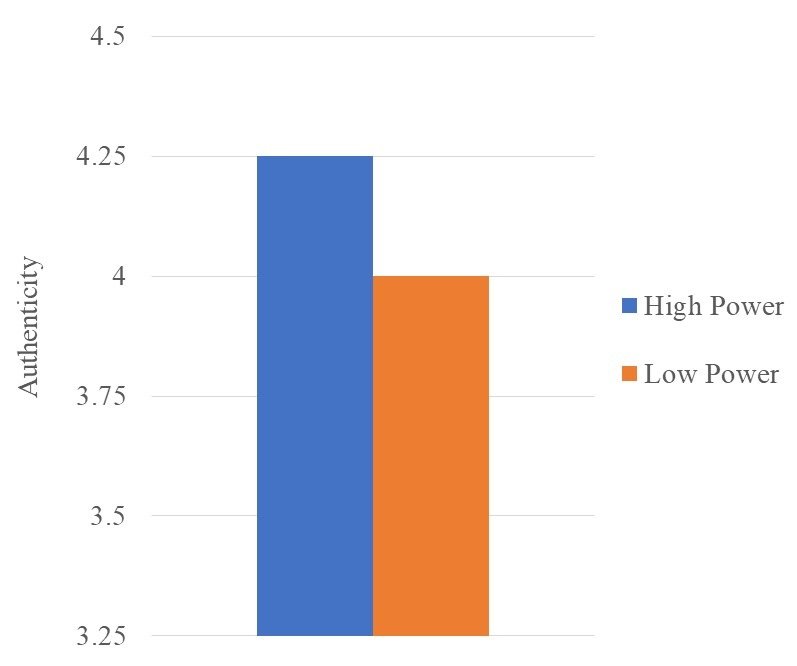

Indeed, numerous studies have shown that whereas low power is tied to inauthenticity (e.g., Wood, Linley, Maltby, Baliousis, & Joseph, 2008), high power tends to breed higher authenticity (e.g., Kifer, Heller, Perunovic, & Galinsky, 2013; see also Gan, Heller, & Chen, 2018; Kraus, Chen, & Keltner, 2011). For example, in one study participants were randomly assigned to spend a few minutes recalling and then writing about either a time they were in a high position of power over someone else, or a time when someone else had power over them. This writing task was meant to momentarily induce participants to feel a high or low sense of power, respectively. Participants then reported on how authentic they felt at the moment. Participants induced to feel higher power reported greater state authenticity relative to those induced to feel lower power (Kifer et al., 2013, Study 2a).

Data from Kifer et al., (2013, Study 2a) show that when participants induced to feel higher power reported greater state authenticity relative to those induced to feel lower power.

In sum, then, experiencing high or low power—such as when we are put in charge of others, or when someone else is put in charge of us, respectively—triggers shifts in the working self-concept. In turn, like any other shift in the working self-concept, this can influence people’s momentary experiences of authenticity.

What Do We Gain by a Working Self-Concept Approach to Authenticity?

So, what do we gain from viewing authenticity through the lens of the working self-concept? At the most basic level, as noted at the outset, such a perspective on authenticity provides a direct answer to the question about which self is being referred to when people are being admonished to be true to the “self” – namely, the particular self that is currently occupying working memory. The present approach also helps to explain apparent inconsistencies, such as when the same behavior—say, for example, being dominant—is experienced in one context to be true to the self (e.g., when giving instructions to a subordinate or when hanging out with one’s younger sibling), but in another context, it’s experienced as inauthentic (e.g., when disagreeing with a superior). The “resolution” is simply that different selves are at play in the two different contexts.

A particularly interesting implication of the present approach has to do with “possible” selves, or the selves that are not yet (or may never be) realized but that are nonetheless stored in memory and seen as genuine reflections of our hopes, fears, values, goals, and so on. Earlier we revealed how ideal selves – versions of the self that reflect who we hope and strive to be someday – are particularly influential in determining whether or not people feel authentic in their relationships with significant others. This means authenticity can spring even from aspects of the self that don’t technically reflect who a person actually is, at least in the present day.

So, for example, a person might have an “acclaimed author” as an ideal self that they are striving toward, and feel particularly authentic when they are thinking, feeling, and acting in ways consistent with their knowledge of what it means to be this self (e.g., making progress on a book manuscript), even if they have not actually become an renown author yet. This phenomenon allows for the possibility of experiencing authenticity even when not-yet-realized or relatively unestablished working selves are at the forefront.

Conclusion

Being authentic is widely thought to involve some version of “being true to the self.” But people possess multiple selves, with different selves at play across time and contexts. So which self does “being true to the self” refer to? From a working self-concept perspective, subjective experiences of authenticity arise from being true to the particular self that has come to occupy working memory and is thus at play in the current moment and context.

Dr. Serena Chen is Professor of Psychology and the Marian E. and Daniel E. Koshland, Jr. Distinguished Chair for Innovative Teaching and Research at the University of California, Berkeley. She is a Fellow of the Society of Personality and Social Psychology, American Psychological Association, and the Association of Psychological Science. Professor Chen was also the recipient of the Early Career Award from the International Society for Self and Identity, and the Distinguished Teaching Award from the Social Sciences Division of the University of California, Berkeley. She was also identified as a Rising Star by the Association for Psychological Science and received the 2022 Mentor Award from this association. Professor Chen is currently the Chair of the Psychology Department.