Muireann O'Dea on boredom, self-compassion, and meaning

Muireann O’Dea is a PhD Researcher in Psychology at the University of Limerick, working under the supervision of Dr Eric R. Igou, Dr Wijnand van Tilburg, and Dr Elaine L. Kinsella. Muireann also completed her BSc in Psychology at the University of Limerick. Her research is centred around boredom and meaning in life. Specifically, she is interested in how positive psychological phenomena, like self-compassion, can increase perceptions of meaning in life to hinder boredom experiences. She has earned multiple scholarships and awards for her research, including an award for research presented at the 2022 Existential Psychology Preconference.

Muireann on the web: Twitter | LinkedIn | Research Gate | Google Scholar

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University. October 28, 2022.

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and existential psychology?

Muireann O’Dea: I’ve always been interested in very practical, logical ways to help make the world a little easier to navigate; I just love to look for solutions to problems. So, originally, I thought I would go into law or some field like that. But then I started taking psychology courses and started to see psychology as the key to better understanding our problems and to developing effective solutions to those problems.

In my third year, I studied abroad at McMaster University in Canada, where I took a module in positive psychology. It was there that I became interested in gratitude, compassion, and forgiveness. Then in my final year, when I returned to University of Limerick in Ireland, I did my undergraduate thesis with Dr. Eric Igou, who does research in the science of existential psychology. It was through reading with him that I became interested in boredom, regret, and disillusionment, and their effects on meaning in life. I became really interested in putting the two together – thinking about how boredom is an unpleasant experience that involves impaired meaning in life, and wondering whether positive psych experiences, like gratitude, might mitigate those negative effects of boredom. That was my first project, then we developed more research studies together, and now I’m doing my PhD on the topic.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great work studying boredom, self-compassion, and meaning in life. Can you tell us more about that research?

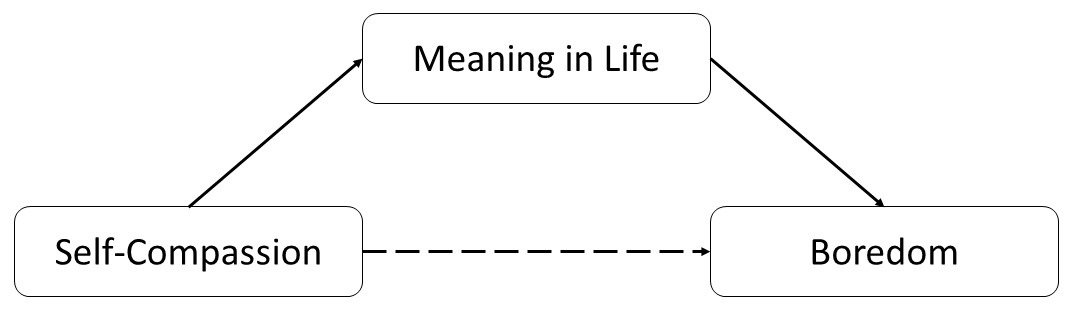

Muireann O’Dea: Absolutely! A lot of prior research has found that boredom is more than just a lack of interesting activity, but is actually linked to a variety of negative psychological and societal outcomes. So, I wanted to explore whether an important positive and existential psychological experience—self-compassion and meaning in life—might help mitigate boredom experiences. Here’s what we mean when we talk about self-compassion, meaning, and boredom:

Self-compassion involves three key experiences: mindfulness, self-kindness, and common humanity.

Meaning in life involves feeling that the world makes sense (coherence), that you are here for important reasons (purpose), and that you’re successfully achieving those goals and impacting others (significance/mattering).

Boredom is the experience of wanting to, but being unable to, engage in interesting activity.

First, self-compassion should be associated with meaning in life because it promotes a sense of coherence, purpose, and significance. It involves a sense of coherence by recognizing the connection between yourself and other people—you’re not isolated in your experiences, you experience joys and suffering just as others do. It involves a sense of purpose and significance, as you maintain an intentional conscious acceptance of yourself—acknowledging that although you may or may not be meeting external contingencies of worth, you are nevertheless a person of intrinsic value who is doing things that matter.

Second, if you have difficulty making sense of the world (low coherence), don’t see your actions as oriented toward a worthwhile goal (low purpose), and don’t think that what you’re doing ultimately matters much (low significance), you probably won’t find whatever it is you’re doing very interesting—and you’ll be bored. But life is much more interesting when it’s easy to understand and when one’s actions feel purposeful and significant. So, greater perceived meaning in life should be associated with reduced boredom.

Data patterns showed that self-compassion was associated with greater meaning in life, which was in turn associated with reduced boredom.

Our theoretical model suggested self-compassion would facilitate a sense of meaning in life, which should then ward off any sense of boredom. To test that idea, we used quantitative survey items (1 = Disagree, 10 = Agree) to measure self-compassion, meaning in life, and boredom (O’Dea, Igou, Tilburg, & Kinsella, 2022). We used structural equation modeling to analyze the results. Indeed, the data showed a mediation pattern, such that self-compassion was associated with greater meaning in life which was itself associated with reduced boredom. We also controlled for positive emotions (e.g., happiness) and negative emotions (e.g., anxiety), so we know these effects were not simply due to positive or negative emotional confounds.

ISSEP: In what ways can your work help us make sense of important recent events?

Muireann O’Dea: Well, the recent pandemic provided a good example of this. Once the pandemic hit, a lot of places went into lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. So, a lot of us suddenly found ourselves at home and without good ways to stay engaged with our typically meaningful activities—for many people it was difficult or impossible to work remotely, to see family, to play team sports, attend school, go on dates, and so on. For many people, that became so painfully boring!

In the USA (left) and Canada (right), some protested to “reopen” society so they could continue doing activities that were meaningful to them, like getting haircuts, massages, teeth cleanings, playing golf, and doing jobs like farming and trucking.

That withdrawal of meaningful activity, and its attendant boredom, is perhaps what motivated some people to want to “reopen” society, to return to a previous way of life they understood—one that made sense—where they could fill their days doing things with interesting purpose and significance. That motivation may have been at work, in the USA, in the protests demanding the reopening of schools and businesses so kids could get back to learning, adults could get back to work, and even take care of meaningful day-to-day activities like going to get their hair cut. In Canada, after a bit more patience, eventually there were similar protests where truckers demanded the reopening so they could return to work as well.

But not everyone responded that way. Many of us practiced self-compassion. For many of us, we recognized our common humanity in that we were all in this together—we were vulnerable just like everyone else, frustrated just like everyone else, and patiently hoping the pandemic would end just like everyone else. We were mindful of the situation, unpleasant as it was, and accepted it and adjusted accordingly. And we exercised self-kindness, recognizing that even though the pandemic may have disrupted our ability to meet our previously-held external contingencies of worth (e.g., reduced work productivity, slower pace of learning at school, wearing sweat pants all day) we still had inherent value and we still were able to do things that mattered.

The result, perhaps, was that simple mindset shifts like practicing self-compassion were beneficial for maintaining a sense of meaning in life during this time and likely buffered against chronic boredom.

ISSEP: Do you see any interesting connections between your research and other material in pop culture?

Muireann O’Dea: Yes! I have this funny routine, where I try to read nonfiction in the morning and then fiction in the evening, and my morning readings often have a sort of pop culture self-help feel to them. For example, I’ve been reading the Dalai Lama’s autobiography (1990), and Eckhart Tolle’s books The Power of Now (1997) and A New Earth (2005). A common theme in those books is mindfulness and being present, of course. But the Dalai Lama also spends a fair bit of time talking about the power of compassion, and how self-compassion is key to meaning in life, which in turn is key for remaining satisfyingly engaged with all that life has to offer. Obviously, their stuff is working with broad concepts, and using broad strokes, but I think it’s cool to see how these sorts of ideas can be tangibly addressed in psychological science—and how some of these claims, at least, might well turn out to be substantiated.

ISSEP: What do you see as the most important next steps in studying boredom?

Muireann O’Dea: I see two interesting next steps. First, I hope to see researchers explore the possible silver linings of boredom, perhaps as a sort of motivational alarm bell. Because boredom is unpleasant, it’s tempting to regard it simply as a nuisance with little or no adaptive merit. But I think, in many ways, it’s completely natural and healthy to occasionally feel bored. It can be a healthy red flag to let us know certain situations or activities are not in line with our values and/or are not what we would otherwise consider worthwhile, and it can motivate us to change course and seek meaningful engagement elsewhere. No doubt such a warning system would be adaptive and could stimulate healthy personal growth.

One possible silver lining is that boredom might, under the right circumstances, stimulate healthy personal growth.

Second, however, prior research suggests boredom’s motivation to seek meaning elsewhere can also sometimes motivate maladaptive and/or anti-social activities. The slightest sign of boredom might motivate people to whip out their smartphones or watch TV shows, which may be a maladaptive use of time. It could motivate aggressive polarization, because outraged defense of one’s moral values can affirm one’s sense of meaning in life—advocating a particular way of understanding the world (coherence) can give people a strong sense of purpose (purpose) and a feeling that they’re having an impact on the lives of others (significance/mattering)—but it might also fuel conflict. Or it could motivate efforts to escape boredom in potentially misguided ways, perhaps by bullying others, overeating, or using or abusing harmful substances. I’d like to see researchers make a more concerted effort to better understand the conditions under which boredom might motivate these sorts of activities, toward the goal of being able to develop interventions that can channel the motivation to seek meaning into more adaptive and prosocial directions.

ISSEP: You’ve attended, and presented research at, our Existential Psychology preconference; how has your experience been with that?

Muireann O’Dea: It was great! I really enjoyed the conference (2022) because even though it was virtual it still felt like an in-person conference. We’d see research talks, interact with the speakers, and take coffee breaks together; the breakout rooms for the poster sessions were great because people would stop by and chat, just like a traditional session; and the social mixer at the end was a fun way to make friends, network, and get to know people further.

I also had some interesting conversations with other researchers who were also interested in self-compassion. We got to chat about our shared interests, swapped papers and feedback about each other’s work, and we’ve been in touch frequently since then so that was a pleasant surprise. And I really enjoyed Laura King’s talk about meaning. I’ve read so much of her work, so it was really cool to see her discuss it. All the other talks were riveting too. The awards ceremony was cool as well, because it helped us know about some of the more important contributions in the field. For example, my lab read the paper that won the Best Paper Award, and it turns out it overlapped with our own work a great deal – it was really a useful way to learn about the field! I just really enjoyed it, all around, and can’t wait to join again!

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

“Look before you leap... First, search out your own interests before you pursue a career in the field. Second, spend the time and effort to scout out a supportive advisor, mentor, or supervisory team. ”

Muireann O’Dea: I’ve got two bits of advice and each of them are about how it’s definitely to your advantage to look before you leap. First, spend the extra time and effort to really search out your own interests and make sure you truly like your topic before you pursue a career in the field, because any one given project can go on for month and months or years and years. You’ll be a lot more successful, and you’ll enjoy the job a whole lot more, if you’re genuinely interested in the topic. Second, spend the time and effort to scout out your advisor, mentor, or supervisory team. It’s such a huge advantage to have supervisors who know your area well, who have the knowledge to help you with your research questions, and who can help translate your ideas into tangible research projects. Additionally, nearly everyone will have moments of doubt (impostor syndrome is real!), but you’ll be so much more likely to find strength in those moments if you have at least one or two established folks who believe in you and are there to support you on things.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the research context?

Muireann O’Dea: I like to keep busy with loads of other things aside from research. I really enjoy traveling and have been trying to get away for city breaks now that the pandemic restrictions are easing up a bit. I just love seeing new places and meeting people from different countries. Actually, one of the things that got me really excited about doing a PhD was the opportunity to travel and meet really interesting people; for example, recently I went to a conference in Chicago and then a training program in Warsaw and had a lovely time at each.

I’m also just a pretty active person, in general. I like CrossFit and yoga and try to do those a couple times a week. I like to go hiking outside, go for sea swims, and most days I’ll make time to meditate as well. I’m here at Limerick on the inlet, but my family’s house is on the Western coast of Kilkee. It’s cold and rainy a lot, here in Ireland, but when the weather’s nice the beach is lovely.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music in the lab; what are you listening to lately?

Muireann O’Dea: I know some people can't stand to listen to music while they work, but I love it. If I’m doing something that takes a lot of attention to do, like cleaning a data file or doing some reading, I'll probably be listening to some type of instrumental lists on Spotify. There's one called “Deep Focus,” which is sort of like Classical and Instrumental Music, so I’ll have that on in the background.

When I don’t need to have such focused attention on work, I look for music with lyrics instead. I love listening to music with lyrics when I'm not working. I’m a rabid Taylor Swift fan, since I was about 12. I love Taylor Swift, so I listen to her a lot; her Folklore and Evermore albums are my faves. But I also listen to a lot of other stuff across a variety of other genres. For example, I really like female singer songwriters, like Maggie Rogers or Phoebe Bridgers. I’m listening to Inhaler a bit recently, which is an Irish band. And I like Del Water Gap; his debut album just came out and it’s pretty chill. I like the singer-songwriter stuff because I feel like I get to know them.