Ethan Trieu, undergraduate research on meaning and self-efficacy

Ethan Trieu recently completed his Bachelor’s in Psychology at Rutgers University Camden, in 2023, and has since matriculated into the psychology department’s accelerated Master’s degree program to continue studying with Dr. Andrew Abeyta. Ethan’s research interests focus on meaning in life as a proactive resource that might be leveraged to enable college students to overcome challenges and move closer to achieving their academic and professional goals. Through this research, he hopes that effective interventions can be developed. Ethan won the 2023 ISSEP Undergraduate Student Research Award for his presentation at the 2023 Existential Psychology SPSP Preconference event.

Ethan on the web: LinkedIn | Research Gate

By Kenneth Vail, Cleveland State University. October 11, 2023.

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and existential psychology?

Top-down from left: Soren Kierkegaard and his statue in the Royal Library Garden in Copenhagen; Jean-Paul Sartre and his Being and Nothingness (1943).

Ethan Trieu: My first encounter with existentialism came after my eighth grade graduation. I had this moment where I thought, “Okay, what’s next? Who do I want to be?” That led me to become deeply interested in learning more about how people develop meaningful goals and then craft their lives to successfully achieve those goals. I got really into watching YouTube video essays that would apply existentialist ideas, from Kierkegaard to Sartre, to understanding why people do the things they do—becoming dentists, going to Disneyland, or donating to Goodwill. Eventually, in my Junior year of high school, I was able to take a psychology course for a semester, but it was just a broad survey course so it didn’t really get into anything like existential psychology.

When I got to college, at University of Rutgers, I took a campus job as a student success coach. In that role, I made some videos emphasizing how higher education and the college experience can be relevant to students’ broader sense of meaning and purpose in life. That video went over really well on campus, and it also led me to learn about and meet Dr. Andrew Abeyta—an existential psychology researcher on campus.

Dr. Abeyta and I started to talk about whether I might be interested in helping to craft some video interventions for some of the studies in his lab, and whether academic meaning might promote efficacy and lead to better academic and professional outcomes. That was really cool, so I followed-up with him and asked if I could help with any of those or other studies in his lab. He accepted me into the lab and, honestly, really leaned into the mentorship—gave me a sort of researcher bootcamp and opened doors to a lot of different intellectual opportunities and experiences that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. At the same time, I really leaned into existential psychological science and took theory and method courses, enrolled in Dr. Abeyta’s lab, and eagerly sought out every learning experience I could get my hands on. I worked on projects that were completed and needed data analyses, projects that were still in progress, and even helped develop some new projects. After a year of two of that, by my Senior year, we started presenting some of our data at conferences and publishing them in scientific journals.

I’ve just recently graduated my Bachelor’s degree in spring 2023, and this fall I’ve begun the Master’s program at Rutgers to continue to do existential psych research with Dr. Abeyta. I was also able to get a graduate fellowship, to help with tuition, so that’s great news as well. My goal is to get some solid training in existential psych science research experience, and then build on that to also get training in therapy and counseling. I’m super excited to put those things together; all of these experiences have snowballed in just the best possible way!

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research on the relationship between college meaning and self-efficacy. Can you tell us more about that work?

Ethan Trieu: Yes. That research (Trieu & Abeyta, 2023) grew out of my collaboration with Dr. Abeyta. Prior research had found that meaning in life promotes self-regulation and self-efficacy. So, we wanted to know whether finding meaning and purpose in college would help students rise to the challenge of successfully navigating college life and accomplishing their academic goals.

In our first study, we recruited 378 college students into a correlational survey. Participants first made quantitative ratings of how much they felt their college educational experiences contributed to their sense of meaning and purpose in life (Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012). Items included statements such as, “I understand how my education contributes to my meaning in life” with scores ranging from 1 (Not true at all) to 5 (Completely true). Then, they completed two quantitative surveys of academic self-efficacy. The first was a nine item measure of self-efficacy for coping with college-related stress (adapted from Benight et al., 2015), with items such as “How capable am I to manage distressing thoughts about challenges in my classes?” with scores ranging from 1 (Not very capable) to 7 (Very capable). The second was a three item measure of self-efficacy for academic achievement (based on Bandura, 2006), with items such as “I feel confident that I can master the course content” with scores ranging from 1 (Cannot do at all) to 10 (Highly certain can do). Even when controlling for GPA and other demographics, results indicated that college meaning was positively associated with students’ self-efficacy for college-related coping and academic achievement.

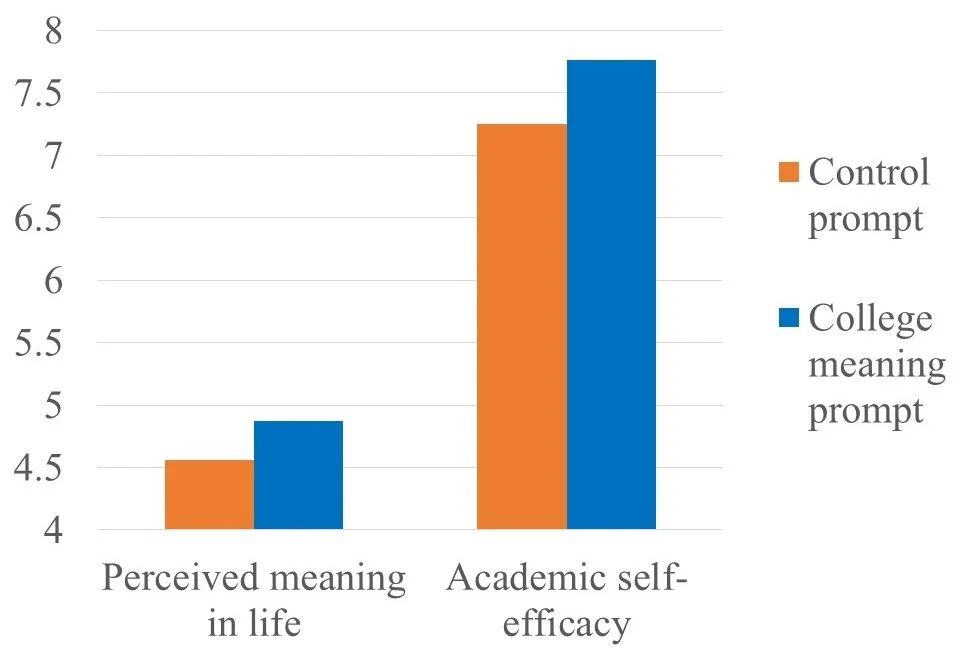

Study 2 found that, compared to the control condition, the college meaning prompt was associated with a stronger sense of meaning in life and a stronger self-efficacy for academic achievement.

In our second study, we recruited 305 students into an experimental design. First, we manipulated college meaning by randomly assigning participants to complete one of two possible writing prompts (adapted from Yeager at al., 2014). In the control condition, participants responded to the following two prompts:

How is college different than high school?

How is your life different now, compared to when you were in high school?

But the college meaning condition, participants responded to the following two prompts:

How does your education contribute to your sense of personal importance?

How will learning in school help you to be the person you want to be or help you make the kind of impact you want to on the people around you or in society in general?

Then, participants completed several quantitative measures of positive affect, meaning in life (Steger et al., 2006), and self-efficacy for academic achievement (same 3-item measure mentioned above). The data patterns revealed that, compared to the control condition, the college meaning prompt was associated with not only a stronger sense of meaning in life but also—importantly—a stronger self-efficacy for academic achievement!

ISSEP: Do you see any interesting connections between your research and changing social trends?

Ethan Trieu: Yes. I think in previous generations, higher education was not yet considered a default life path; people really only went to college if they had the privilege and felt higher education was a meaningful step toward their life’s goals. But in recent generations, higher education has become more widely accessible, is associated with higher income and social status, and so for many people the question of attending college is given little thought—it’s simply the next step after high school. As a result, I think students can sometimes have difficulty seeing how their higher education experiences might be relevant to their broader meaning and purpose in life.

John Green, author of The Fault in Our Stars and one half of the Green brothers, discussing the economic value of education (worth it) compared to its existential value (very worth it).

Instead, they might ask whether college is “worth it,” in terms of whether the money spent on a college degree will produce a suitable return on investment in the form of more dollars earned over the course of one’s subsequent career. If they anticipate a sufficient return on investment, they might grudgingly attend (and not necessarily study well!), collect the degree, and move on to their careers; but if they don’t see much money in it (e.g., English Lit or Philosophy degrees), they might struggle to get the most out of the experience or might even choose to skip it entirely.

That’s exactly the sort of process we’re hoping to better understand and address with our research. Our findings show that seeing college as relevant to one’s broader meaning and purpose in life—such as seeing it as contributing to one’s personal growth and the betterment of society in general—is important for fueling one’s self-efficacy to cope with the stresses of college and achieve one’s academic goals. The experiment we ran, in Study 2, even suggests that simple interventions can help amplify college meaning and self-efficacy. Perhaps campus student success coaches, and/or educational agencies and institutions, could leverage meaning and purpose based interventions to promote student success in higher education for the general improvement of self and society.

ISSEP: Do you see any interesting examples of your research topic in the arts and culture?

Ethan Trieu: Yes, there are a lot of good examples in film. From Animal House (1978) to Slackers (2002), there’s an entire genre of “college disaster comedies” depicting students who are, to put it mildly, not exactly having the best student success experiences. In these films, there’s usually at least one scene that touches on why, and either subtly or overtly suggests that the characters don’t really see the point of studying, learning their course material, or having productive college experiences. They just don’t see it as relevant to their broader sense of meaning and purpose in life. Instead, they’re typically just going through the motions, and having fun along the way, such that once they graduate (or flunk out) they’ll move on to pursue more important things in their lives.

Left to right from top: Animal House (1978); Slackers (2002); Good Will Hunting (1997); and Hidden Figures (2016).

Even films that do take higher education and intellectual achievement seriously, such as Good Will Hunting (1997), grapple with questions about whether and how people see their educational activities as part of their broader meaning and purpose in life. Will Hunting (Matt Damon) developed his prodigious abilities in math, presumably, because he felt it was intrinsically enjoyable. But, spending his time drinking with friends and having run-ins with the law, he clearly never connected his broader sense of purpose in life to the development of his mathematical skills or the application of his abilities to the improvement of society. Professor Gerald Lambeau (Stellan Skarsgard) and Dr. Sean Maguire (Robin Williams) intervened to try to help Will find meaning and purpose in developing his abilities and making intellectual contributions, but too little too late. Will resisted and eventually left math, mentors, and friends behind to go “see about a girl” (Skylar, played by Minnie Driver) in California.

At the opposite end of the spectrum are films that highlight the success stories of people who recognized that education and academic achievements are critical to their broader meaning and purpose in life. One great example is the film Hidden Figures (2016). The film follows mathematicians Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), Dorothy Vaughan (Octavia Spencer) and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monae) as they perform endless calculations as human “computers.” However, in contrast with the above films, each of these women construe their intellectual abilities as meaningful tools for pursuing their purpose in life—to elevate themselves and their communities, and contribute to the successful exploration of space.

When Mary gets assigned to the heat shield team, she excels, and is encouraged to apply for an engineer position. The position, however, requires additional courses. With the goal squarely positioned within her sense of meaning and purpose in life, she is filled with a sense of self-efficacy and rises to challenge after challenge to successfully accomplish her goal. She overcomes her husband’s protests, petitions a judge for permission to attend classes at the local all-White high school, attends night courses and diligently studies the relevant math, and ultimately became NASA’s first Black female engineer. Her advances and contributions have been recognized in countless awards, a satellite was named after her in 2020, and in 2021 the Washington D.C. headquarters building was even renamed the Mary W. Jackson NASA Headquarters.

Each of these examples illustrate the importance of meaning and purpose in helping people to stay motivated, believe in their own ability to meet challenges, and ultimately to successfully accomplish one’s goals in a particular academic area.

ISSEP: You’ve attended, and presented research at, our Existential Psychology Preconferences; how has your experience been with those?

Ethan Trieu: The 2023 Existential Psychology SPSP Preconference was my first conference presenting research, so I was incredibly nervous. I’m not sure exactly what I expected, but I was sure it would feel like an interrogation and that people would be trying to “find something” that I didn’t know about or didn’t do correctly. Obviously, that’s not how it works. Instead, I was happy to find that all the attendees were super friendly, asked excellent questions, and had helpful suggestions. People kept rotating through to my poster, I got great practice sharing about my research, and I met so many awesome researchers. Honestly, it was such a kind and supportive community, I didn’t want the poster session to end. I’m definitely looking forward to doing it again!

“First, find a good mentor.

Second, be flexible about your research interests.”

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Ethan Trieu: First, one of the most important things is to find a good mentor. You can probably do a lot of learning on your own, but once you reach a certain point you really need someone who can show you the ropes. You’ll want someone who can give you supportive, robust mentoring, and take you under their wing. So, I think finding a solid mentor is super important.

Second, be flexible about your research interests, especially while you’re in undergrad or graduate training. There are so many content areas to explore, so many methods to master, and a host of statistical techniques to learn. Look for a mentor and other researchers who have advanced research programs, join in on those, and learn to do what they’re doing. As an undergraduate that will help turbo-charge your training experiences, as a graduate student it will help broaden your horizons, and then once you’ve gained sufficient expertise and seniority you can begin to form and pursue your own mature research program.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the research context?

Ethan Trieu: I read a lot of manga and watch a lot of anime. I’m finally caught up on the notoriously long anime One Piece (if that means anything to anyone!), and I like to collect the memorabilia and merchandise from that and my other faves.

Outside of that, I play the guitar and love to write and play music. It was on the backburner a bit after I became involved in research but I’m getting back into it again. I write songs that are mostly just for myself—little things I sing in my head and then match up with the instrument. As a result, a lot of the songs are thoughtful and introspective, some of them express anguish, and some are metaphors about different aspects of life. The style is often similar to folk, sometimes pop, and always acoustic.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music in the lab; what are you listening to lately?

Ethan Trieu: Right now I’m listening to a song called “For Right Now” by my friend Albert Tang. It’s been on my playlist rotation and it’s got a killer guitar solo at the end. I also listen to a lot of Good Kid, which is pretty much the opposite of the sort of music I play and sing. It’s very fast paced and electric; super bouncy! My favorite of theirs is called Osmosis, which has some really interesting instrumentals.

I think the way I listen to music is it gets coded in my brain as the soundtrack for the “seasons” of my life. Not following the seasons, like the weather, but life episodes. For example, there might be a 4- or 5-week period of time where I’ve been “liking” songs and adding them to my playlist, just letting the list roll on repeat, and it gets so intertwined with whatever I was doing at that time. Sometimes really great stuff happens during that “season,” so when I hear one of those songs a few years later it’ll transport me back to that special time. But other times, a “season” of life gets tough, and that’ll just be a batch of songs that I might have enjoyed at the time but that I’ll never want to hear ever again because it would just tear me to pieces. Anyway, my musical interests seem to change from season to season in life.