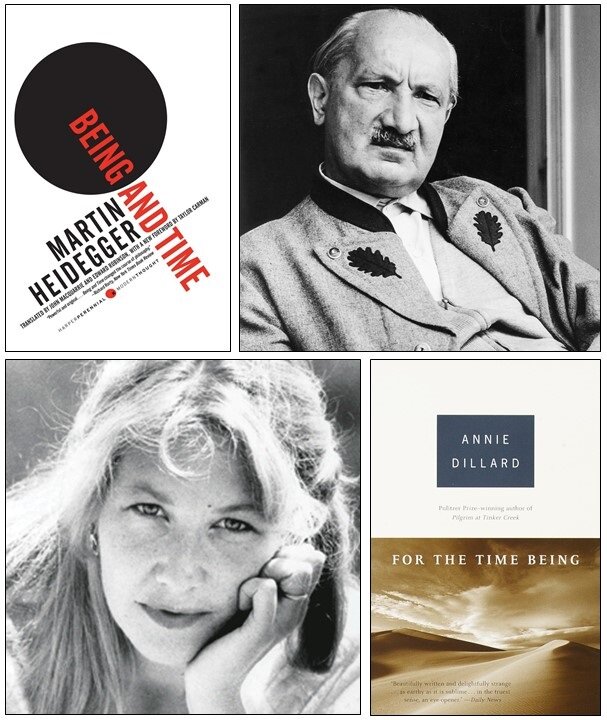

Being and time… for the time being

Clockwise from top left: Being and Time (1927); Martin Heidegger; For the Time Being (1999); and Annie Dillard.

Skidmore College. June 23, 2021

“There were no formerly heroic times, and there was no formerly pure generation. There is no one here but us chickens, and so it has always been: a people busy and powerful, knowledgeable, ambivalent, important, fearful, and self-aware; a people who scheme, promote, deceive, and conquer; who pray for their loved ones, and long to flee misery and skip death. It is a weakening and discoloring idea, that rustic people knew God personally once upon a time—or even knew selflessness or courage or literature—but that it is too late for us. In fact, the absolute is available to everyone in every age. There never was a more holy age than ours, and never a less.”

- Annie Dillard, For the Time Being (1999)

In the early 1980’s, my colleagues and I (Jeff Greenberg, Tom Pyszczynski, and myself) read Ernest Becker’s The Birth and Death of Meaning (1971) and The Denial of Death (1973), which inspired the development of terror management theory. Two years ago, I read Martin Heidegger’s Being and Time (1927) for the first time. I had heard of the overlap between Heidegger’s views and the ideas of American transcendentalists (especially Emerson), pragmatists (especially William James), and J.J. Gibson’s ecological and Gestalt approaches to perception, but I had been avoiding the book since the last millennium because of its daunting length, seemingly impenetrable prose, and my personal antipathy toward Heidegger in light of his Nazi sympathies. When I finally got around to reading it, and thinking about it, I was pleasantly surprised to find it intriguing, provocative, and potentially fertile ground for future theoretical and empirical experimental existential psychological inquiry.

Accordingly, my goal in this missive is to provide a “classic comic book” overview of Being and Time with a few dangling afterthoughts in hope of encouraging others to get acquainted with Heidegger (and exchange ideas with those already familiar with this discourse).

Human beings vs. humans’ being

At the outset of Being and Time, Heidegger contends that Western philosophy made a colossal mistake that persists to this day. To illustrate, he points to Plato’s Theaetetus, which includes a dialogue concerning the nature of knowledge and serves as an allegorical account of the origins of philosophy. The tale consists of a philosopher, a well, and a servant girl. The philosopher is so absorbed in his celestial contemplations that he is oblivious to his terrestrial surroundings and tumbles into the well. The servant observing the spectacle bursts out in hearty laughter.

Clockwise from left: Plato’s Theaetetus; Frans Hals’ portrait of René Descartes; and Caspar D. Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818), which contemplates the meaning of humankind’s expanding mastery over nature.

Traditional philosophy developed by following the philosopher’s perspective in Theaetetus—head in the clouds and trafficking in abstractions, viewing humans as beings (noun) in intellectual pursuit of pure theory, culminating in Descartes’ famous declaration: “I think therefore I am.” Humans, from this perspective, are depicted as disembodied, detached, acultural, ahistorical, solitary monads in a mathematically precise universe devoid of meaning or purpose. This, Heidegger notes, is not to discount the value of this approach for practical purposes—it led to the science that got humans to the moon. It cannot, however, provide any insight about why we might want to go there or what we should do there once we arrive.

Humans are the only form of life for whom the question of meaning arises; accordingly, Heidegger insists that What is the meaning of being? is (or should be) the superordinate question for philosophical and psychological inquiry; study humans’ being rather than human beings. This requires that one go back and start philosophizing from the servant’s perspective in Theaetetus by examining the everydayness of living, in pursuit of what philosopher Silvia Benso describes as “embodied wisdom.”

Each of us is “thrown” into the world at a specific time, place, and culture: a body of beliefs, values, practices, and artifacts. We immediately “fall” into this humanized “world” and are absorbed in, engaged with, concerned about, and affected by, that world. We are assimilated into a culture and adopt the language, rituals, practices and preferences, and social roles afforded by it in our particular place and time. From this perspective then, we are not, nor were we ever, disembodied spectators dispassionately perusing the world from an exalted vantage point. Rather, we are culturally-saturated dynamically-engaged entities who care deeply about ourselves and our surroundings; this is manifested, according to Heidegger, in terms of understanding, mood, and discourse.

Understanding consists of implicit familiarity with, and comprehension of, one’s physical and cultural surroundings, without which any subsequent explicit intelligibility would be, as William James might describe it, “as one great blooming, buzzing, confusion.” By the time, for example, you “wake up” one day and realize that you are in America you are already an ambulatory cultural artifact: your name is a social introjection; you recognize the McDonald’s Golden Arches (Happy Meal) and the Nike Swoosh (“Just Do It”) before you can walk or talk; you know that Santa is a good guy and Satan is evil.

Mood is explicit and implicit affect based on one’s own mood, the mood of those in one’s immediate surroundings (e.g. a graduation versus a funeral), and the tenor of the times (e.g. The Roaring 20’s versus The Great Depression).

Discourse is the use of language as a means of discovery and communion, above and beyond its communicative function; as Julian Jaynes put it: “Language is an organ of perception, not simply a means of communication.”

Back to the future—now!

Heidegger extends his analysis of humans' being by declaring that “…time [is] the horizon for any understanding whatsoever of being…”, making a distinction between linear and existential time. Linear time is how most of us understand and generally experience time: an orderly progression of standardized humanly-constructed units—seconds, minutes, hours, days, years, centuries, etc.—that unfold in an ongoing succession of “nows,” bookended by the past (“nevermore”) and the future (“not yet”). Concurrently, one lives in existential time: non-linear, recursive, and varying in subjective duration, like an undulating pulsating mobius-strip as opposed to a straight line as a depiction of linear time. One is always oriented toward the future as a being that cares about… well… something! But what one cares about is always a reflection of the past, which also informs our understanding about how to proceed in the present moment. This is in part why William Faulkner famously declared that “The past is never dead. It's not even past."

Angst

Being a being in time inevitably, Heidegger asserts, gives rise to, in varying quantities and degrees of awareness, angst, or anxiety, a uniquely human and foundationally existential affectation. Angst is more than general worry or apprehension; it also connotes a sense of the uncanny and being unsettled or not-at-home. Angst results from the awareness (which need not be explicit) of the inevitability of one’s death: a uniquely personal event that cannot be overcome and marks one’s complete and utter obliteration.

Most people, indeed everyone from time to time, “flee” from angst by taking refuge in their cultural scheme of things and their social role in the context of their culture as the primary basis for deriving a sense of meaning and value. They become anxious meat puppets tranquilized by culturally constructed trivialities in a frenetic flight from death. (This is, of course, a central tenet of Ernest Becker’s work and terror management theory.)

We do not, however, inevitably flee from angst. Rather, (and here Heidegger is following Kierkegaard) angst can also serve as a calling, summoning us to find our own real selves. Angst reveals the fictitious and ultimately groundless nature of the cultural scheme of things and one’s role in it as arbitrary and intrinsically meaningless. I realize, for example, that although I am a psychology professor from New York in the 21st century, I could just as easily be an illiterate goat herder in 3rd century Mongolia; or, a goat.

While this realization is unsettling, it is also potentially liberating. We can, in such a “moment of vision,” which may take considerably longer than a minute and occur without explicit awareness, come to terms with our mortality: not as the eventual culmination of our life at some vaguely unspecified future moment; but rather, as an ever-present possibility. Moreover, we can accept responsibility for our life choices despite them being limited by determinative factors over which we have no control and assuage existential guilt by accepting, as Henry Miller declared, that “We are all guilty of crime: the great crime of not living life to the fullest.”

What would someone be like in the aftermath of this kind of existentially authenticating transformation? Echoing the Buddha’s insistence that “enlightenment is quite ordinary,” Heidegger proposes that although the world would look the same, for the most part, and one would still be a historically situated cultural artifact, to a certain degree, one is returned “to its particular place in its world, to its specific concernful relations with entities and solicitous relations with others in order to discover what its possibilities in that situation really are and to seize upon them in whatever way is most genuinely its own.” After this roar of awakening, being is characterized by “anticipatory resoluteness” (i.e. looking forward with admirable determination and purpose) where life is experienced as an ongoing adventure perfused with “unshakeable joy.”

“Although we are here today, tomorrow cannot be guaranteed. Keep this in mind! Keep this in mind!”

Living authentically does not eliminate suffering or angst. Rather, it fosters a general state of psychological well-being conducive to managing existential terror with humility and grace, instead of malignant manifestations of a frenetic flight from death that yields demoralized, hateful, warmongering, proto-fascists plundering the planet in an insatiable quest for dollars and dross in a Facebook, Netflix, Amazon, TikTok, Twittering, alcohol, Xanax stupor. In his later work, Heidegger viewed humankind’s increasing reliance on technology as an ominous form of death-denial, suggesting this reflected a thinly-veiled effort to create an “infinite standing reserve” of power and energy rather than accepting, and working within the confines of nature.

As I mentioned at the outset, I found Heidegger’s ideas interesting and potentially generative. His phenomenological account of finding one’s own-self in a moment of vision strikes me as, like gratitude and humility and nostalgia, a potent existential anxiety buffer that is personally uplifting with potentially prosocial downstream effects (“concernful relations with entities and solicitous relations with others”). I also find myself curious about why Ernest Becker devoted so little attention to Heidegger in The Denial of Death as a secular alternative to Kierkegaard (a leap of faith in life rather than in God), as well as why, outside of a few rare and notable exceptions (Reuther, 2014), Heidegger’s work has garnered so little attention in contemporary psychological scientific discourse.

Sheldon Solomon is Professor of Psychology at Skidmore College. His studies of the effects of the uniquely human awareness of death on behavior have been supported by the National Science Foundation and Ernest Becker Foundation, and were featured in the award winning documentary film Flight from Death: The Quest for Immortality. He is co-author of In the Wake of 9/11: The Psychology of Terror and The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. Sheldon is an American Psychological Society Fellow, and a recipient of an American Psychological Association Presidential Citation (2007), a Lifetime Career Award by the International Society for Self and Identity (2009), and the Association of Graduate Liberal Studies Programs Annual Faculty Award (2011).