Chaotic suffering, blame, and moral outrage

By Lucas Keefer

University of Southern Mississippi. May 7, 2021

As the coronavirus spread, in early 2020, the world began to grapple with an invisible, diffuse, and poorly understood hazard. In the earliest days of the pandemic, some, such as US President Donald Trump (Keith, 2020), initially assured the public it was completely under control. Then, as concern grew, he denied it as a political hoax that warranted neither concern nor action. But when the chaos and suffering ultimately became overwhelming, and undeniable, Trump and other similar public figures had no other choice but to join the rest of the world in trying to make sense of it: What caused the virus? What should be done about it? Was that cough just a cough or something more? What, or who, was safe anymore—and what, or who, wasn’t?

Rather than an invisible, diffuse, and poorly understood viral threat, Trump and his allies began to reinterpret the pandemic’s chaos and suffering in terms of orderly and controllable political problems. Additionally, as critics began to blame the President and his administration for failure to safely manage the crisis, he began to portray himself and his allies as morally virtuous victims of evil forces. Indeed, Trump began to blame China for the outbreak (Griffiths, 2020; Mason & Spetalnick, 2020) and began referring to COVID-19 as the “China Virus” or the “Wuhan Virus” (Marlow, 2020; Marquart & Hansler, 2020). In expressions of moral outrage in interviews, at rallies, and in formal policy positions he painted himself as the righteous victim of malicious forces at home and abroad—accusing the Chinese government, the World Health Organization (W.H.O.), and the Democratic Party of each working to worsen the situation (McNeil & Jacobs, 2020). As experts feared (Chiu, 2020; Rogers, 2020), that sort of discourse led to a rise in harassment, violence, and other hate crimes against Asian-Americans (Hart, 2020; Tavernise & Oppel, 2021).

To better understand reactions like these, my colleagues and I have spent years researching reactions to uncertainty. That work has revealed systematic mental processes oriented toward quickly understanding a world that might otherwise seem absurd and uncontrollable, taking meaningful action in it, and navigating it in ways that allow people to see themselves and their choices as morally righteous.

Compensatory control theory

Theory and research (e.g., Landau, Kay, Whitson, 2015) suggests that people are indeed motivated to perceive that the world is a systematic and predictable place that can be meaningfully controlled either by their own personal actions or the actors and agencies inherent in their broader cultural systems (e.g., God, government). When people’s sense of personal control is undermined, they compensate by turning to external systems to maintain order and control; and, vice versa, when those broader cultural systems appear to lack sufficient control, people compensate by bolstering faith in their own personal abilities.

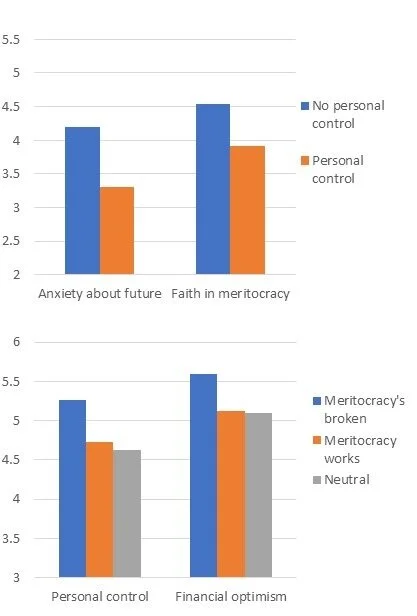

Data patterns reproduced from Study 2 of Goode, Keefer, & Molina (2014) shown in the upper graph and data from Goode & Keefer (2015) in the lower graph.

External control. Data are consistent with these ideas (Kay et al., 2008). When research participants recalled a time in their life when they felt powerless, they subsequently reported an increased belief that events in our lives are effectively controlled by God, or, in other studies, by overarching systems of government. Other research (Kay et al., 2010) has similarly found that when circumstances undermine faith in one external force (e.g., God), people increase faith in another (government). In my own experiments on the topic (Goode, Keefer, & Molina, 2014), my colleagues and I found that although a diminished sense of personal control caused participants in a control group to feel pessimistic about the future, such anxieties were eliminated when people read information suggesting the American economic system is fair and rewards hard work (meritocracy). Thus, it appears people can render their own powerlessness less terrifying by reassuring themselves that someone or something out there in the world is effectively looking after their best interests.

Personal control. On the flip side, when such external forces seem ineffective, individuals can compensate by subjectively inflating a sense of their own sense of personal control. For example, in one early experiment (Kay et al., 2008), participants were randomly assigned to watch either a video on a control topic or a video suggesting society is sometimes incapable of effectively achieving justice. When participants were shown the video suggesting the system was broken, they subsequently reported greater confidence that they personally could control the things happening in their environment. In one of our own studies (Goode & Keefer, 2015), we found that when participants were shown information suggesting the American economic system was not a fair meritocracy that distributed resources on the basis of hard work, they too subsequently increased their confidence in their personal sense of control—which then sustained their reported sense of optimism about their future economic prosperity. When people don’t feel like they can rely on their broader systems to exert sensible control, they compensate by putting their faith in their own ability to weather the storm.

Uncontrollable chaos and suffering? People prefer a tractable villain

That theory and research is important because, sure enough, we humans are regularly faced with situations where it seems like the world is full of uncontrollable chaos and suffering, and that our broader systems aren’t able to exert sensible control. We grapple with questions like: Why do we get cancer, why do we go hungry, and why must we endure the widespread suffering of deadly pandemics?

Most of us, however, don’t know. We’re not experts in biology, economics, or public health, and even if we were it’s not clear that any of these fields are advanced enough (yet) to provide satisfying answers. Yet, because chaos and suffering are both a psychological conundrum and an existential threat, people are of course motivated to try to come up with meaningful answers to questions like these so that we can do something about them. On that point, cultural anthropologist and existentialist Ernest Becker, in his 1969 book Angel in Armor, noted that encountering chaos and suffering in the world is a psychological problem, and argued that we resolve it by looking for ways to localize that threat in terms of people, objects, or situations that can be more easily controlled—and then trying to take steps to control those things.

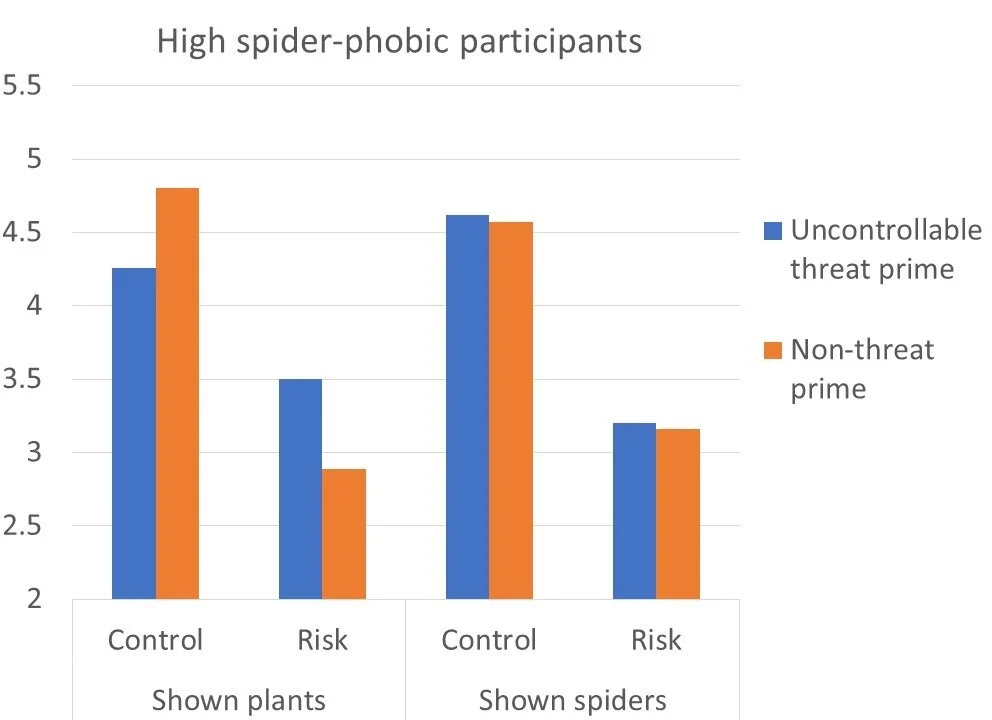

Data patterns reproduced from Study 2 of Rothschild, Hauri, & Keefer (2020).

Some of our own research confirmed that idea (Rothschild, Hauri, & Keefer, 2020). We measured participants’ level of arachnophobia (fear of spiders), then we randomly assigned them to be reminded of either predictable suffering (e.g., lung cancer from smoking) or chaotic suffering (e.g., randomly developing cancer), and then we showed them pictures of either plants or spiders. Reminders of chaotic suffering (vs. predictable suffering) led participants with fear of spiders to report feeling lower personal control and greater risk of experiencing a set of 10 life-threatening events (e.g., heart attacks). However, when they were shown pictures of spiders (vs. plants), that effect was eliminated—they regained their sense of personal control and no longer felt any elevated risk of life-threatening harm. Although these participants were reminded of chaotic suffering, they could now localize the fear—one might not be able to do much about chaos, but at least one can take meaningful steps to avoid spiders.

Of course, most people don’t tend to blame spiders for the chaos and suffering in the world. For that, people tend to blame each other—other agents capable of malevolent influence. Indeed, multiple experiments have found that when participants low in personal control were exposed to reminders of diffuse and chaotic hazards (e.g., food poisoning, natural disasters), compared to controllable hazards (e.g., alcohol consumption), they attribute greater influence to villainous—yet more tractable—social forces (Sullivan et al., 2010). For example, one study found people reminded of chaotic suffering attribute greater influence to their personal enemies, and another found they more strongly believe their political enemies were manipulating elections through mail-in-ballot fraud, voter intimidation, or blatantly tampering with election machines. Importantly, this research found that individuals (ironically) felt more in control of their lives when they read about a villain conspiring to cause them harm.

When people encounter situations that remind them the world can be an unpredictable and dangerous place, they tend to feel powerless and unable to do anything about it. Although it may sound odd, the data show that people can actually feel empowered and safer when they focus their fear onto a more tractable villain that they can do something about (Landau…& Keefer, 2012; Sullivan…& Keefer, 2014).

Righteous indignation: Existential function of moral outrage

In addition to greater epistemic certainty facilitating a sense of meaningful action and control, outrage against tractable villains may also help facilitate people’s sense that they’re morally righteous and that their actions are not only significant but also—in the grand scheme of things—admirable. Indeed, existentialist Carlo Strenger pointed out, in The fear of insignificance (2011), that when societal dynamics highlight the possibility they may have failed to live up to cultural values and expectations, people are drawn toward conflicts—however seemingly trite—that can provide even a fleeting sense that there is a clear sense of true good and evil in the world and that they’re on the side of good.

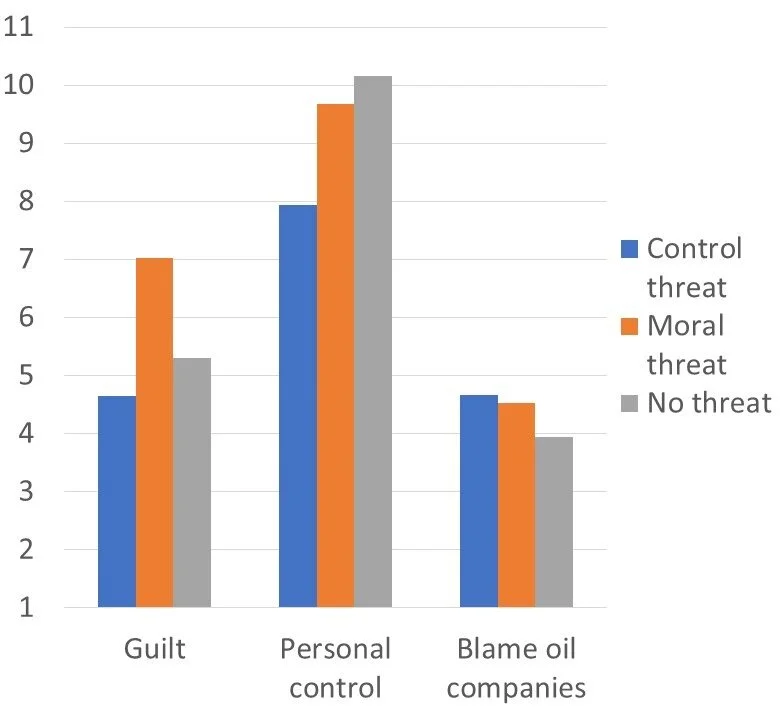

Data patterns reproduced from Study 1 of Rothschild… & Keefer, (2012), showing the effect of control threats and moral threats on guilt (1-13), personal control (1-13), and desire to blame and punish the oil companies (1-6).

My colleagues and I investigated this possibility in a series of experiments (Rothschild… & Keefer, 2012). We had participants consider the often amorphous and seemingly intractable problems of environmental destruction and climate change. We framed these problems either in neutral terms (no threat condition), as chaotic suffering caused by unknown sources (a control threat), or as caused by their own harmful personal lifestyle choices and actions (a moral value threat). Then we asked participants to rate how much they (a) felt guilty for the environmental harm, (b) felt like they had no personal control over it, and (c) felt like a tractable villain was to blame: Oil companies. Compared to the neutral no-threat condition, when we framed the problems as caused by their own actions they felt more guilt and when we framed the problems as chaotic they felt reduced personal control—and both led them to more strongly blame the oil companies.

In related studies (Rothschild & Keefer, 2017), we either gave participants an opportunity to express moral outrage at corrupt corporations who profit from sweatshop laborers, or did not give them that opportunity, before we measured their sense of guilt. When we framed sweatshop labor as caused, in part, by their own actions (a value threat) they reported feeling guilty—but not if they were able to first express their righteous indignation about the unethical corporations. In a follow-up study, we had people reflect on a past virtuous act they did and found diminished moral outrage afterward.

These data patterns suggest that one main reason people scapegoat or blame others, beyond restoring a sense of personal control, is to absolve themselves of moral culpability by laying greater blame elsewhere and by portraying themselves as innocent, virtuous, and admirable.

Pandemic politics: Chaos, guilt, and scapegoats

This research helps to better understand why, at least in the American context, events such as the COVID-19 pandemic seem to have elicited so much political finger-pointing from those in power. Certainly, President Donald Trump faced a difficult situation, with infections spreading out of control. Amid such a cloud of confusion, chaos, and suffering, the present research suggests, existential motivations would lead him to look for ways to reconstrue the problem in ways that seemed to involve a greater sense of systemic and personal control, opportunity for meaningful action, and one’s moral virtue.

Such existential motivations (Palitsky et al., 2020; Rothschild, Keefer et al., 2021) help explain why he and others began to blame China for the outbreak, accuse the W.H.O. of trying to help them cover it up, and accuse the Democratic Party of working to make him look guilty for the widespread sickness and death. If it were the result of nefarious actors elsewhere, the problem would no longer be an intractable source of despair and one would no longer be guilty for such massive loss of lives and livelihoods. With righteous indignation, pundits and politicians could simply point the finger at enemies to neutralize the psychological threat of a chaotic and dangerous world and paint themselves as virtuous heroes “fighting the good fight” against those evil forces. The tragedy, of course, is that finger pointing by Trump and others did nothing to relieve the pandemic, and racialized scapegoating led to a rise in hate crimes and other physical abuses against Asian-Americans.

Thus, research studies like these show that existential concerns about chaotic suffering may fuel scapegoating, because it can function to restore a sense of control and preserve confidence that one is morally righteous and culturally valued. Although these are not the only motivations behind social conflict, existential psychology further raises new questions about how the search for meaning, in a chaotic and dangerous world, can sometimes spill over into socially disastrous consequences.

Lucas Keefer is an Assistant Professor at the University of Southern Mississippi. He earned his PhD in social psychology from the University of Kansas, and minored in quantitative psychology. His research has focused on the practical significance of conceptual metaphor and the existential psychology of enemyship and scapegoating, with implications for a number of basic areas in social and personality psychology, including attitudes and persuasion, political psychology, and social cognition.