The Role of Shared Reality in Shaping Meaning

IESE Business School. July 30, 2025.

Clip from the 2007 film, Into the Wild, in which McCandless—facing his mortality alone in the Alaskan wilderness—realizes that “happiness is only real when shared.”

In Into the Wild (1996), Christopher McCandless abandons the trappings of modern life in search of meaning in the wilderness. Disillusioned by materialism and inspired by literary figures such as Thoreau and Tolstoy, he cuts ties with his past, renames himself "Alexander Supertramp," and ventures into the Alaskan wilderness, believing that true meaning is found in solitude and self-reliance. His story, immortalized first in a book and in later a film, struck a chord with audiences, reflecting our society’s enduring fascination—some might say obsession—with the search for meaning, or in other words, the desire to experience life as coherent and purposeful (Steger et al., 2006).

Yet, McCandless’s final journal entries reveal an ironic twist to his journey: after months of isolation, he arrives at a stark realization—"Happiness is only real when shared." His search for meaning, initially framed as a solitary pursuit, ultimately suggests that meaning may not be found in seclusion, but rather in connection. This message reflects a key element often overlooked in the search for meaning: the role of relationships. My research mirrors McCandless’ story, providing evidence that we cannot exclusively pursue meaning on our own.

Meaning as a fundamental need

We have long recognized the fundamental need for meaning as central to the human experience. One of the seminal pieces of literature on the topic was Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) where he describes his experiences as a prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp during World War II. This memoir tragically illustrates the deeply ingrained need to find meaning imbedded in all of us, which Frankl refers to as the “primary motivation in [man’s] life”. In the most horrifying circumstances, Frankl reflects on the importance of meaning beyond all else:

Victor Frankl and his book, Man’s Search for Meaning (1946).

“Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.”

This need is echoed in modern research: As humans, we have a fundamental need to experience meaning in our lives. Decades of research suggest that fulfilling this need is central to well-being. This includes psychological well-being, such as making us happier and more satisfied with our lives, as well as physical well-being, such as reducing our stress and morbidity. Given these benefits, it’s no wonder we are driven to seek meaning in our lives—but how do we find this sense of meaning?

Interpersonal approach to meaning

Meaning in life has long been considered a deeply personal pursuit—one shaped by individual goals, values, and existential reflection. But is it possible that our long-held view of meaning as a solitary pursuit is misguided?

Let’s look back at what Viktor Frankl has to say on the subject:

“By declaring that man is responsible and must actualize the potential meaning of his life, I wish to stress that the true meaning of life is to be discovered in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system.”

Beyond just looking to the world, as Frankl so beautifully urges us to do, in my work, my colleagues and I find data patterns to suggest that we look to those around us. Mirroring Christopher McCandless’ ultimate realization in Into the Wild, emerging research, including my own, suggests that meaning is not solely an individual endeavour. If you ask people to recall the most important and meaningful moments in their lives, they involve the people closest to them (Klinger, 1977). In fact, people overwhelmingly list personal relationships as their primary source of meaning (Fave & Coppa, 2009). In my research, my colleagues and I find that meaning is co-constructed through our relationships, particularly with our closest others, our romantic partners.

Consider a real-world example of a pressing and complex societal issue: racism, a central focus of one of my studies on meaning in life. Imagine you are a Black American living through the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd and the anti-Black racism protests that followed. You might find yourself wondering: What can I do? How can I help? How should I engage with the movement? And in grappling with these questions, you would likely turn to those closest to you—perhaps most notably, your romantic partner. Together, you attend protests and discuss your experience of racism. In doing so, you align on your understanding of the movement and how to engage with it, ultimately allowing you to experience a greater sense of meaning in your life.

As this example illustrates, there is something in our interactions with the people closest to us that shapes our sense of meaning. I argue that this something is the process of aligning our perspectives about the world around us. In my research, my colleagues and I demonstrate one key way romantic partners create meaning in their lives: by co-constructing shared inner states about the world around them with others, that is, by creating a sense of shared reality.

Shared Reality

Shared reality is defined as the perception of sharing inner states—such as attitudes, feelings, and beliefs—with another person about the world in general (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021).

Experiences of shared reality arise naturally in daily interactions, like when romantic partners share a laugh over an inside joke or colleagues align on how to approach a project. In my research, shared reality is defined as the perception of sharing inner states—such as attitudes, feelings, and beliefs—with another person about the world in general (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021).

For instance, when Janine perceives that her romantic partner, Mike, shares her feelings about a movie they just watched, she experiences a sense of shared reality with him. This momentary feeling of being “on the same wavelength” can be felt in many other areas, such as the memes they both enjoy or their opinions on political candidates. As Janine continues to experience these shared realities with Mike across different topics, she may start to feel a broader sense of shared reality with him about the world in general, which influences how she interprets the world, navigates uncertainties, and ultimately how she derives meaning from her life.

Shared Reality Theory suggests that humans are naturally driven to establish a sense of shared reality with others as this helps fulfill two core psychological needs: the need to connect with people and the need to make sense of our surroundings. When we experience shared reality with someone—whether it’s agreeing on a big life decision or simply laughing at the same joke—it makes us feel more connected to them and gives us a greater sense of certainty. Research, including my own, shows that these benefits go beyond just having a happy relationship or receiving high-quality support from our partner.

Experiencing a shared reality with another person is especially important for the process of meaning-making because it is a subjective perception about something–like a person, event or idea–outside of the relationship. This characteristic makes shared reality uniquely able to capture how two people converge on their views of the external world. This differs from typical ways researchers measure relationships, which tend to focus on how two people see their relationship or see one another (e.g., relationship satisfaction, perceived partner responsiveness: Rossignac-Milon & Higgins, 2018). Rather, shared reality captures a dynamic of a person’s relationship that influences their experiences beyond the relationship and about the world at large.

Examining the relationship between shared reality and meaning in life

Considering the role shared reality plays in helping us make sense of the world around us, my colleagues and I sought to test whether shared reality with a romantic partner, arguably our closest other, could influence our experience of meaning in life. In a series of studies, we explored how shared reality with a romantic partner reduces uncertainty and enhances our meaning in life and work (Enestrom et al., 2024). Participants completed measures of shared reality, uncertainty, meaning in life and, in one study, meaning in work.

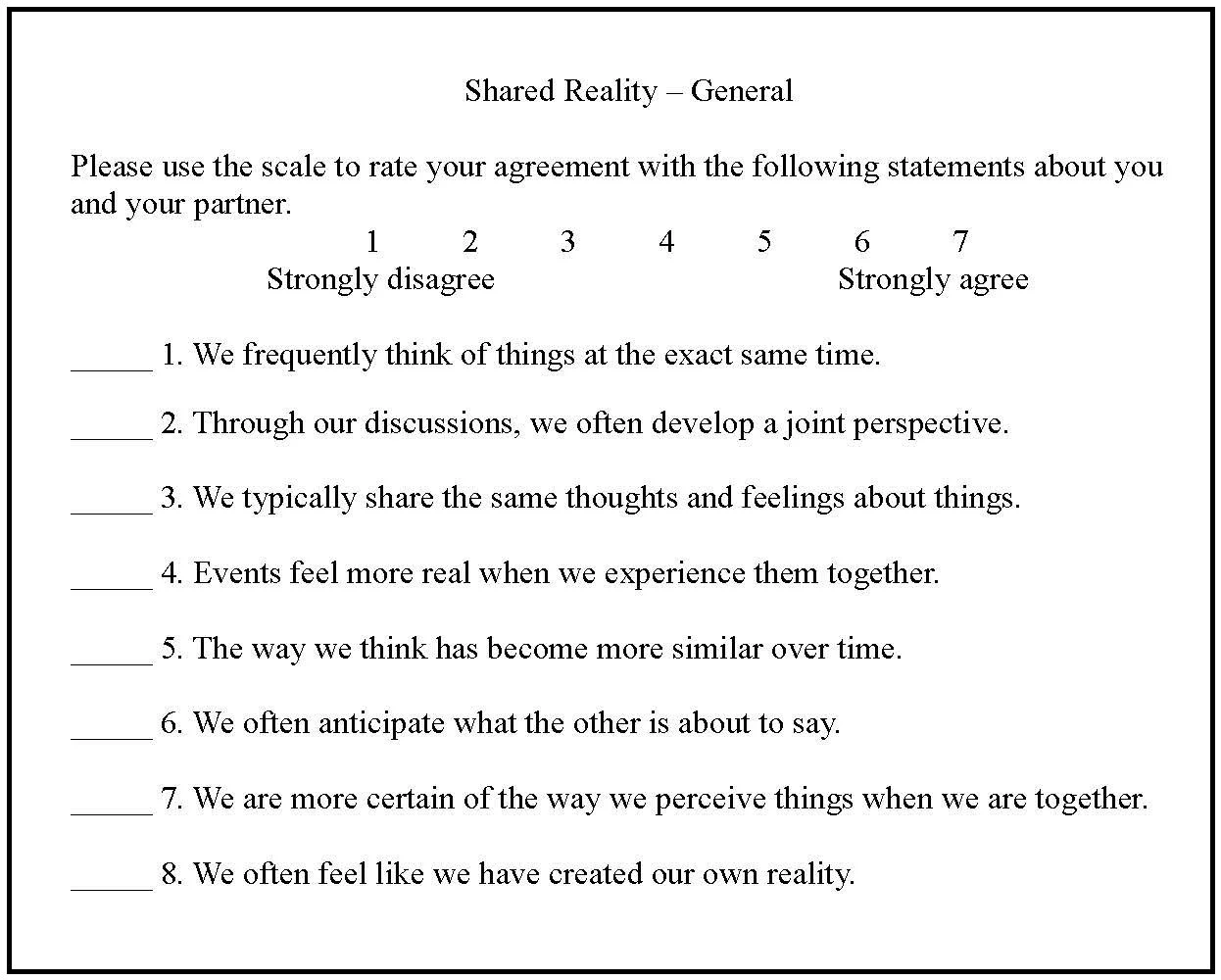

Participants’ sense of shared reality with their romantic partner was measured using the “Shared Reality - General” instrument (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021).

We measured shared reality using a set of statements that asked participants to rate the extent to which they felt on the same wavelength as their romantic partner (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021). Example statements included “We typically share the same thoughts and feelings about things” and “Events feel more real when we experience them together”, which were rated on a 1-7 scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree).

We measured uncertainty using 3-reverse scored statements, such as “I am certain of what I think is really going on” (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) (Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021). This measure was adapted to the context of each study: For instance, when examining uncertainty in a sample of Black Americans navigating the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of George Floyd, we asked about their uncertainty with respect to racism and the sociopolitical climate.

Lastly, we measured meaning in two ways. First, to capture meaning in life in four of our studies, we had participants complete five statements, such as “My life has a clear sense of purpose” on a 1-7 scale (1 = Absolutrely true, 7 = Absolutely untrue) (Steger et al., 2006). To capture meaning in work, participants responded to four statements including “I understand how my work contributes to my life’s meaning” (1 = Absolutrely true, 7 = Absolutely untrue) (Steger et al., 2012).

Real-world relevance

Across five studies, including longitudinal and experimental designs, we found that shared reality fosters greater meaning by reducing uncertainty about one’s environment. This effect emerged in two contexts of significant societal relevance: Black Americans navigating the complexities of racism and frontline healthcare workers navigating an uncertain workplace during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data from Study 2 (Enestrom et al., 2024) found that Black Americans who had a strong sense of shared reality with their romantic partners felt less uncertain about racism and the sociopolitical climate, which in turn made their lives feel more meaningful.

In the first context, we examined how shared reality with a romantic partner influenced Black Americans’ experiences of racism following the murder of George Floyd and amidst the Black Lives Matter protests. We found that Black Americans who had a strong sense of shared reality with their romantic partners felt less uncertain about racism and the sociopolitical climate, which in turn made their lives feel more meaningful. In other words, when you feel on the same page about the world with your partner generally, including about your experiences in society (e.g., how to process experiences of discrimination, how to engage with social movements), you gain more clarity about navigating these challenges. As a result, you can extract more meaning from your life.

Data from Study 3 (Enestrom et al., 2024) found healthcare workers who experienced a stronger sense of shared reality with their romantic partners felt more certain about their work, which in turn made their work feel more meaningful.

We also wanted to see if this pattern applied to the workplace, where meaning is just as essential as it is in other aspects of life. In fact, work is the second most common source of meaning, right after family (Pew Research Center, 2021). People dedicate a significant amount of time to their jobs (Pryce-Jones, 2010) and tie much of their identity to their occupations (Kirpal, 2004). Research has also found that experiencing meaning in work promotes greater meaning in life (Steger & Dik, 2009).

Given the importance people attribute to their work, we studied frontline healthcare workers during the first two waves of the pandemic to explore whether shared reality with a romantic partner could extend into their work experiences. Our findings showed that, over time, healthcare workers who experienced a stronger sense of shared reality with their romantic partners felt more certain about their work, which in turn made their work feel more meaningful. In other words, when you and your partner align on aspects of your life, including your work—such as team dynamics, work-life balance, and career aspirations—the more certain you feel about aspects of your job (e.g., how to approach a new project, or how to delegate different tasks). This results in a greater sense of meaning in your work. Across both studies, these results could not be explained by relationship satisfaction. Instead, the shared reality that participants had with their partners was critical to a sense of meaning, regardless of how generally positive they viewed their relationships to be.

This research highlights the significant impact of romantic relationships on how we experience meaning in the real-world. When we feel like we are “on the same wavelength” with our romantic partners, that sense of alignment can shape how we experience complex situations in our lives, from racism to life-threatening work conditions. These findings highlight the power of shared reality in helping us navigate life’s experiences, even when our partners might not be going through the same experience, or when the experience is extremely uncertain and difficult.

Experimental evidence

Beyond these real-world contexts, we wanted to show that these effects were truly driven by shared reality, leading us to test these effects experimentally. In an experiment, we demonstrated that the benefits of shared reality could be extended to everyday experiences by focusing on moments of shared reality that naturally occur in daily life. Specifically, we recruited participants in romantic relationships and randomly assigned them to recall a moment when they felt on the same page as their partner (high shared reality) or a moment when they did not (low shared reality). After reflecting on these experiences, participants reported their level of uncertainty about the recalled event and their sense of meaning in life. Here are some examples of what participants recalled:

High Shared Reality:

We looked at a house to purchase. We both had the same feelings about all the historical features of the house. We also had the same ideas on how to make the house fit our needs better.

Low Shared Reality:

What happened between us is that we disagreed on how to handle a specific situation in the workplace. I thought it was unacceptable behavior of the coworker, but they did not share the same sentiment.

As predicted, those in the high shared reality condition (compared to the low shared reality condition) experienced less uncertainty about the event they recalled—like the home they were considering purchasing—which predicted greater meaning in life. Importantly, these effects could not be accounted for by participant mood, relational conflict, or general relationship satisfaction.

Together, these findings suggest that shared reality is not only a fundamental component of close relationships but also a powerful mechanism for making sense of the world and finding meaning—whether in daily life, during societal challenges, or in the workplace. Even the smallest shared moments, such as simply laughing at the same meme, can play a role in shaping our perception of meaning.

Why shared reality matters

A sense of shared reality can help us feel connected to others and serve an epistemic function, reinforcing our confidence that our perceptions are valid and real—giving us the confidence that we do indeed understand the meaning of a situation.

Why is shared reality so powerful? Unlike other ways that researchers tend to measure interpersonal relationships, which often focus on how partners view their relationship or regard one another (e.g., relationship satisfaction), shared reality specifically captures the sense of being “on the same wavelength” with a partner. This alignment serves an epistemic function, reinforcing our confidence that our perceptions are valid and real—giving us the confidence that “we get it”.

For example, a Black American witnessing racial injustice may struggle to make sense of their experiences, a doctor overwhelmed by the pandemic may struggle to understand their work, or a potential homeowner may feel unsure about making such a large financial commitment. Each of these instances may be understandably difficult to make sense of, but if their partners validate their interpretations of these events and share in their perspectives, the world feels more comprehensible and less chaotic (i.e., more meaningful).

Critically, our findings held even when controlling for relationship satisfaction. This is important because it means that shared reality is not merely a byproduct of being in a happy relationship—it is a distinct process that enhances how we experience and understand our world.

This is only the beginning

Our understanding of the benefits of shared reality for meaning in life and work is in its infancy stage. For instance, do these benefits extend to other types of relationships, like those with friends, family members, or coworkers? Although we would expect this to be the case, some of these relationships are cultivated across a narrower range of contexts, which might impact the extent to which shared reality broadly promotes meaning in life. Epistemic trust (i.e., trusting another person’s perspective) could play a role here, where shared reality is particularly meaningful with people who are seen as a reliable and credible source of information.

While shared reality generally reduces uncertainty and fosters meaning, there may be times when a lack of shared reality is beneficial. For example, moments of initial misalignment—like a friend introducing you to a new cuisine—can expand your experiences and create new sources of meaning. Additionally, what people build shared reality around may vary based on their background and context. For instance, shared reality about racism may be more central to meaning-making for Black individuals than for those who don’t regularly experience racial discrimination. Exploring these nuances can help us better understand how shared reality shapes meaning across different relationships and situations.

Although there is still much to uncover, one things is clear: shared reality with romantic partners plays a crucial role in fostering meaning in our lives. Ambiguous situations often make it difficult to interpret and navigate the world around us, but by turning to a romantic partner, we can create understanding out of chaos and ultimately find purpose in the world we co-construct.

I urge you to embrace this process—engage in activities that promote shared reality, such as joint experiences and regular, meaningful communication. Doing so will not only deepen your relationships but also enhance your sense of meaning—both in life and at work. This research highlights the profound impact of shared reality in transcending personal relationships, shaping how we interact with and make sense of the broader world.

Dr. Catalina Eneström is a Postdoctoral Research Scholar in the department of Managing Peoples at IESE Business School. She received her PhD in Experimental Psychology from McGill University in August 2023. Prior to her PhD, Catalina received her Bachelor of Commerce at McGill University, half of which was completed at the Universidad Torcuato Di Tella in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In addition, she has worked in consulting, sales, and marketing at international companies in various cities across Canada and in Argentina. Catalina’s research examines how people rely on their interpersonal relationships to make sense of their experiences at work and in life. As part of this research, she explores how interpersonal relationships with close partners or coworkers help people experience meaning in their lives and in their work. Relatedly, Catalina explores how unshared experiences undermine the benefits provided by interpersonal relationships, such as work-life balance. Her work has been published in journals such as the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.