Navigating Happiness and Meaning in Life

By Fan Yang

The University of Chicago. July 31, 2025.

Do you know the scene from The Sixth Sense where the kid whispers, “I see dead people. They walk around like normal people. They don’t even know they’re dead”?

Well, I see dead activities—and I bet you have too. The routines we’re expected to follow, the jobs we should do, the parties we’re supposed to enjoy. Even entire lives can feel empty and meaningless. Whether we admit it or not, sometimes there could be a nagging sense that our lives are filled with to-do lists, that we’re just going through the motions with occasional interruptions of happiness.

We are living in an era marked by unprecedented technological advancements and a plethora of entertainment choices when we want to have fun, yet surveys show that people are no happier than they were decades ago. Not just that, a growing sense of existential unease has emerged in recent years, reflected in terms like "languishing," "quiet quitting," and "lying flatism." There is a profound sense of being lost—unsure of what to pursue in life or what kind of life to aim for.

We all strive to experience happiness and meaning, but why does it elude us despite the plethora of opportunities to experience it? Where does this sense of existential unease and being lost come from? Do we, too, need a Sixth Sense––not for seeing dead people, but for sensing what truly matters? We wrestle with these questions because we’re not content with living a life only made of to-do lists and fleeting joy—we long for something more. But how do we find what truly matters?

The Modern Promise: Do Quick Fixes Really Fix?

In a world of urgency, distractions, and checklists, time is not just money––it’s a scarce resource. When we need something, we want it delivered instantly, NOW, including happiness. In response to the growing deficit of happiness and meaning, a flood of quick, actionable tips has emerged—"12 Habits for Happy People," "10 Simple Steps to a Meaningful Life," and so on.

Quick fixes have their appeal: they offer something quick, easy, and concrete––they make the seemingly elusive concepts of happiness and meaning more achievable. But here’s the truth: even if following quick fixes could help us find brief moments of happiness and meaning in life, they do not give us direction. In a world moving faster than we can keep up, no matter how much we achieve or how well we perform, we feel pressured and insecure if we don’t know where we’re headed. Even if we could experience perfect happiness over and over again, the anxiety remains if we don’t know whether our efforts will lead to something we can feel proud of in our lifetime. Quick fixes can’t fix this for you.

In fact, the whole idea that happiness and meaning can be engineered through a quick checklist overlooks something fundamental about humans: we don’t just need to complete the day’s tasks, feel good in the moment, or optimize life in short bursts. We also need to take a bird’s-eye view of our lives, evaluating how we’re doing in the long run—and we need to know that our pursuits align with our deeper aspirations for life as a whole.

To achieve this, the mere experience of happy and meaningful moments may not be enough: we also want a deep understanding of what happiness and meaning mean to us. In fact, much like having a “sixth sense”, we all likely hold some implicit notions of what happiness and meaning mean—and we often feel a sense of unease when we’re not acting in alignment with these hidden ideas. It’s just not always easy to articulate them. My research aims to bring these hidden insights to light.

Seeing Clearly: Making Happiness and Meaning Less Elusive

Even though the concepts of meaning and happiness may seem elusive, we are not as clueless about them as we might think.

We actually form judgments about meaning and happiness with surprising ease. When we hear about an event, observe someone’s career, or reflect on our own choices, we instinctively know whether they feel joyful or meaningful. And these judgments are far from random—they could show remarkable consistency within individuals and surprising consensus across people. For example, few would find counting blades of grass or living the life of Sisyphus deeply meaningful––our intuitions are shaped by shared underlying principles.

My work taps into these intuitive perceptions to uncover the deeper conceptual structures of happiness and meaning in our mind. As we will see below, we actually have deep understanding of happiness and meaning within us even from childhood, even though we’re not explicitly aware of them.

Pleasure = Happiness, Right? Not So Fast…

When we talk about happiness, we often think of pleasure—the feeling of satisfaction or enjoyment. Some philosophies, like hedonism, see happiness as simply the pursuit of pleasure. Undoubtedly, having pleasure is important and we may not even desire to live if we didn’t have pleasures in life. However, why do people usually talk about “a happy life” rather than just a “life of pleasure”? Do we expect something more than pleasure when we think of happiness?

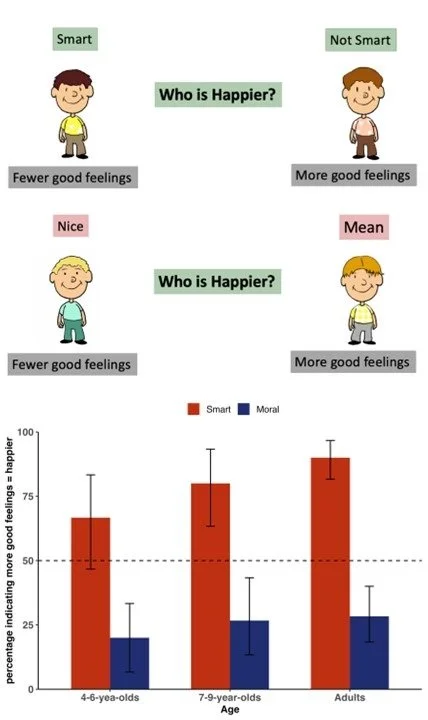

Upper: Illustrative stimuli for the smart and moral stories in Yang, Knobe, and Dunham (2021). Lower: Results indicated that happiness can come from feeling good but also from being good even when being good doesn’t necessarily feel good.

Some philosophers, like Aristotle, offer a deeper view: happiness comes from the pursuit of virtue, not just pleasure. For him, true happiness is about being good, not just feeling good. This perspective challenges the idea that happiness is merely about experiencing pleasure. Which view better captures what happiness means to laypeople?

In a study where we asked 100 adults what happiness means, 99 mentioned things like enjoying movies or spending time in nature, with only one person mentioning kindness (Yang, Knobe, & Dunham, 2021). Therefore, it seems that for most people, happiness is closely linked to feeling good and having pleasurable experiences. If we had stopped there, the conclusion may have been happiness = pleasure. However, we kept going.

We conducted additional studies to more directly examine the role of moral judgment in our views of happiness. For example, we told stories about a person who gets everything they want and feels good every day but is very mean to others. Most adults and children as young as 4 or 5 regarded such a person as not happy.

Moreover, the effect seems to be specific to moral character, rather than other positive traits like intelligence. For example, when comparing a smart person (who finds everything boring and experiences fewer good feelings) to a less smart person (who finds everything interesting and experiences more good feelings), both adults and children rated the less smart person as happier because of their positive feelings. However, when comparing a kind person (who feels sad when others suffer and has fewer good feelings) to a mean person (who enjoys stealing and experiences more good feelings), both children and adults agreed that the kind person was happier.

These findings demonstrate that moral character plays a crucial and unique role in shaping our views of happiness, revealing that, even from an early age, we recognize that pleasure alone is not enough for happiness and happiness is not about being a taker.

The Pursuit of Something Bigger Than Ourselves: Where Happiness Falls Short.

Happiness is only part of the puzzle of avoiding the dreaded “dead activities.” Humans are meaning-making beings. Yes, we want to feel good, but we also want to know we are doing something meaningful with our lives. But aren’t happiness and meaning kind of the same thing? Sure, but not really. Meaning and happiness are often mentioned together as important parts of a good life, but our research suggests that they differ in one important way—our perceptions of meaning focus more on self-transcendence than our perceptions of happiness (Huang & Yang, 2023).

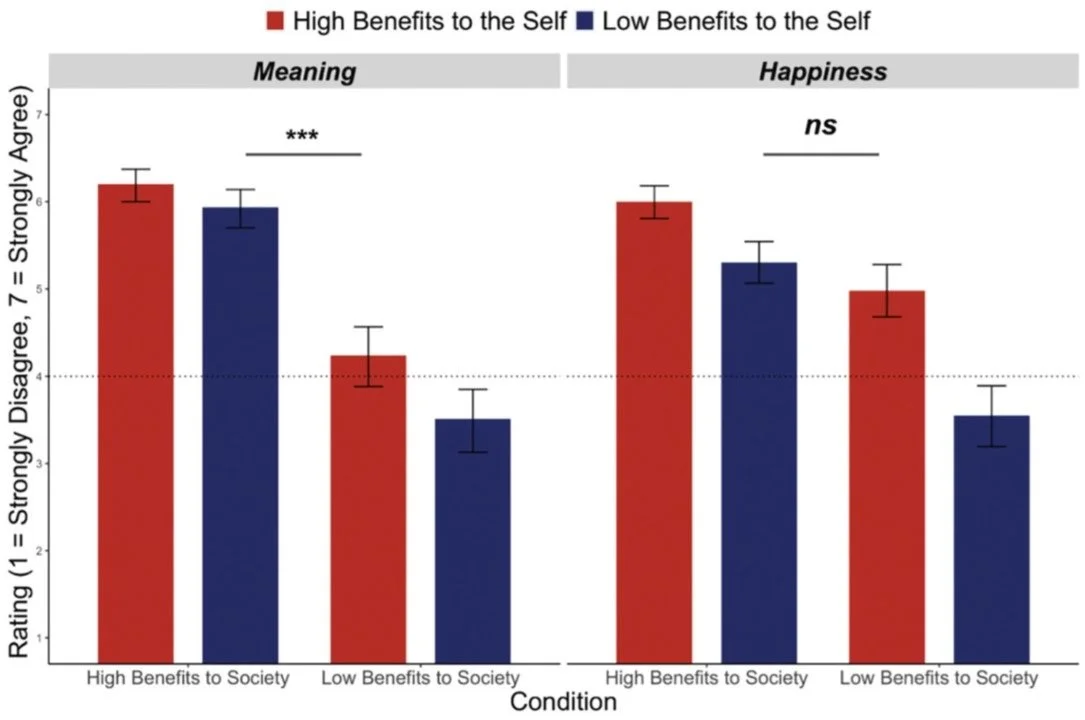

For example, we asked U.S. adults to rate 15 different jobs (from drug dealers to professors) on four simple questions: How much does the job benefit the self, benefit society, bring happiness, and bring meaning? We found that, for meaning, what matters most is how much the job benefits society or others (self-transcendence), rather than benefiting the self (self-enhancement). But when it comes to happiness, both self-enhancement and self-transcendence are equally important.

In Study 2a of Huang and Yang (2023), participants suggested others can build meaning by doing activities that benefit society and build happiness by doing activities that benefit themselves.

We tested this idea further in another experiment where people gave advice to others who lacked meaning or happiness in their lives. Both types of activities were seen as useful, but people were more likely to recommend activities that benefit society for those lacking meaning, and they recommended both self-enhancing and self-transcendent activities equally for those lacking happiness.

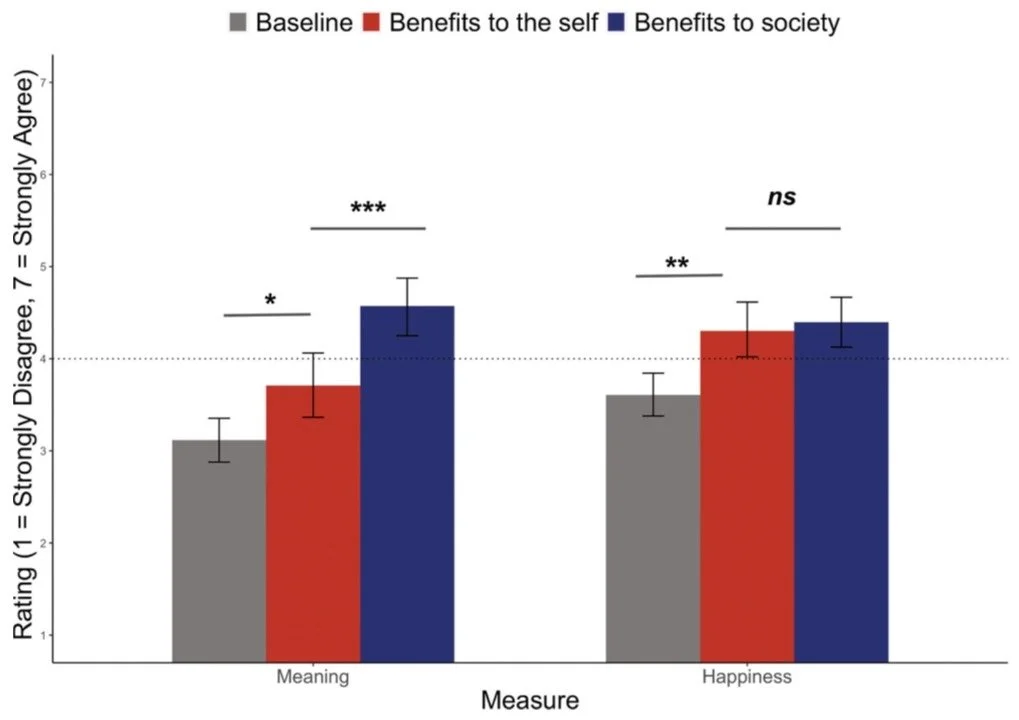

In Study 7a of Huang and Yang (2023), framing a photo-identification task as benefiting the self (personal reward) or society (pandemic healthcare project) led to similar levels of happiness, but framing it as benefiting society led to greater levels of meaning.

To explore how these perceptions manifest in real-life experiences, we conducted another experiment in which we asked people to complete a simple photo-identification task, either for a small personal reward (self-enhancement) or to help develop machine learning for fighting a pandemic (self-transcendence). Both types of framing led to greater feelings of happiness and meaning compared to completing the task without such framing. However, framing the task as benefiting society led to greater feelings of meaning, while both frames resulted in similar levels of happiness.

Across studies, our findings consistently suggest that meaning is perceived as more self-transcendent than happiness, highlighting a key distinction between the two. Taken together, there seems to be a consensus: to have happiness, we need to fulfill our desires—but without harming others. But to have meaning, it means we also need to contribute beyond the self.

Beyond the “Quick Fix” Mindset: Trusting Our “Sixth Sense” for Happiness and Meaning

Does knowing these findings instantly make you happier or give your life more meaning? Probably not. Do they offer a simple set of actions to follow? Definitely not. And that’s exactly the point. We don’t just need quick fixes for happiness and meaning—we need insight. These findings help illuminate the often hidden notions and underlying ideas behind what happiness and meaning truly mean to us. And that illumination serves as a blueprint—the first step toward designing and living a life that genuinely aligns with our deepest values and aspirations.

It’s hard to ignore the constant noise of modern life—the demands, the distractions, the endless expectations. It’s only natural to try to quickly fix each of them, one by one. But do we really have to keep up with everyone else’s pace or meet all the external pressures placed on us? Perhaps external noises matter so much because we don’t have a strong inner compass of our own.

That’s why a “quick fix” mindset is not enough. What we need is a guiding beacon––an inner orientation to ensure we’re heading in the right direction. This will allow us to confidently, and even joyfully, lose ourselves in the process. The good news is (and this is backed up by rigorous research) that deep, inherent understandings of happiness and meaning are already within us, even though we are not explicitly aware of them all of the time. While the individual paths we take may differ, the core principles are widely shared. It’s time to bring these hidden truths into clearer focus for yourself.

As we’ve seen, people value moral values and self-transcendence when it comes to happiness and meaning. Living according to these ideals is both challenging and lifelong. It takes time to reflect on our values—not just on what feels good in the moment, but on what makes us feel good about who we are—and commitments that help us not only enhance ourselves, but also transcend ourselves. Each of us may also need to find our unique ways of realizing these values. It may take a lifetime to discover, refine, and live by them. There are no one-size-fits-all quick solutions, and no one can do it for us.

But choosing this path will make life a more rewarding journey. By aligning our lives with our core “sixth sense”––our personal understanding of happiness and meaning––rather than being at the mercy of “dead activities”, we are more likely to achieve what truly matters to us, to live fully, and to embrace the one and only life we have.

Fan Yang is a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Chicago, where she directs the Human Nature and Potentials Lab. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania and completed her postdoctoral training at Yale University. Her research explores how people ask and answer life’s big questions—such as why we live, what meaning and happiness is, and who we want to become. Her work has shown that even young children hold intuitions about these existential topics and possess greater moral and emotional potential than we often assume.