Sliding doors: Unexpected Pathways to Meaning in Life

Achva Academic College & The Compass Institute for the Study and Application of Meaning in Life. August 15, 2025.

"Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love." – Rainer Maria Rilke

What makes people change, grow, and transform? This question has animated my research over the years, rooted in the belief that to be fully alive—not merely existing—we must engage meaningfully with life’s inherent uncertainty. Rather than avoiding discomfort, existential psychology invites us to meet it with openness and authenticity.

Moments That Change Us

We often think of anxiety as a problem to be solved. But what if, as Rilke suggests, anxiety is also an invitation? In our research on transformative life experiences, we found that anxiety can catalyze a process of positive authenticity—where one’s sense of self becomes clearer and more aligned with one’s values.

We live in a culture that rewards confidence and control. Yet it is often in our moments of deepest uncertainty that we find clarity about what really matters. Take, for instance, the experience of someone who unexpectedly loses their job—a moment fraught with fear, confusion, and self-doubt. What initially feels like a collapse of identity can become, over time, a turning point: a chance to rediscover long-suppressed passions, re-evaluate one’s purpose, and choose a more authentic path. A crisis, a challenge, or an unexpected encounter may disrupt the flow of our ordinary days—and yet plant the seeds of new insight and purpose. When the familiar develops cracks, this disruption—whether small or seismic – enables us to glimpse parts of ourselves we have long forgotten. These experiences invite us to ask: Who am I, truly? What is worth my time? What do I want to become?

The Catalyst of Positive Anxiety

Sometimes, a single moment can split a life in two. In the 1998 film Sliding Doors, we follow Helen, whose life unfolds along two parallel timelines—one in which she catches a train and discovers her partner’s betrayal, and one in which she misses it and remains unaware. In both versions, a seemingly mundane event triggers a cascade of disorientation, self-doubt, and ultimately, transformation. The film poignantly illustrates how unexpected disruptions—those “sliding doors” of life—can awaken existential questions and prompt a profound reevaluation of one’s values, direction, and identity.

In real life, too, existential anxiety often begins with such disorienting experiences: changing careers or communities after years of stability, receiving a serious diagnosis, facing failure, or enduring a sudden loss. What follows is rarely linear. Denial, fear, and confusion may surface. Yet, those who are able to stay present with the discomfort—rather than flee from it—frequently emerge with a renewed sense of clarity and authenticity. They describe feeling “more alive” and more attuned to what truly matters (Russo-Netzer, 2025; Russo-Netzer & Davidov, 2020).

Unlike fear, which is tied to a specific threat, existential anxiety emerges from confronting life’s ultimate givens: mortality, freedom, isolation, and the absence of inherent meaning. It is a diffuse unease born of deep awareness—of finitude, of the groundlessness of existence, and of the radical responsibility we have to shape our lives. While unsettling, this form of anxiety can also act as a wake-up call—prompting greater intentionality and presence.

Our qualitative study, based on in-depth, semi-structured interviews with over 200 adults who had undergone self-identified transformative life events, examined how such experiences are lived and interpreted (Davidov & Russo-Netzer, 2022; Russo-Netzer & Davidov, 2020). Thematic analysis revealed that emotionally intense and disruptive moments often served as catalysts for existential reflection, dismantling familiar assumptions and prompting re-evaluation of priorities and alignment with deeper values. Consistent with Heidegger’s view (1962), when people confronted the absence of pre-given meaning with openness rather than avoidance, existential anxiety could transform from a source of distress into a bridge to greater authenticity, connection, and meaning.

And yet, anxiety doesn’t always lead to meaning. Our findings point to a crucial distinction: those who viewed their anxiety not as a stop sign, but as a call to act, were more likely to initiate meaningful change. For them, discomfort became a doorway to greater clarity and alignment. Indeed, many participants in our study described a kind of existential “reset”—a moment when life suddenly took on new urgency and depth. These inner shifts often translated into outward changes: leaving unfulfilling jobs, rebuilding relationships, or reimagining long-held goals. This echoes Viktor Frankl’s insight that anxiety may function as a spiritual alarm clock— not a signal to suppress, but one to heed.

Positive anxiety arises when disruptions crack open our routines and invite us to choose more consciously. Meaning, in this light, is not passively found but actively forged—through interpretation, commitment, and choice. In moments of uncertainty, we are offered a rare chance to recognize our freedom: to reinterpret, reimagine, and realign with what truly matters. When the familiar falls away, we confront not only our mortality, but also the responsibility to reclaim authorship over our lives. Meaning, then, is not given—it is created through reflection, action, and the courage to move forward, even in doubt. Existential anxiety can thus become a quiet catalyst—a nudge toward authenticity and presence. In the heart of uncertainty lies a hidden gift: the possibility of becoming more whole, more awake, and more deeply alive.

A Meaningful Surprise: Synchronicity and the REM Model

Must you go through a major life event to find renewed purpose? Not necessarily. Meaning can also emerge from subtler, more uncanny moments. One such source is synchronicity: personally significant coincidences that feel imbued with meaning. Carl Jung described it as “the coincidence of events in space and time as meaning something more than mere chance” (Jung, 1950/1997, p. 25). These moments align inner experiences with external events that occur close in time, in ways that defy conventional causal logic. In our studies, participants recounted diverse examples: dreaming about someone and meeting them the next day, thinking of a question and hearing the answer in a song lyric, or encountering a book, person, or phrase at a moment that felt perfectly timed. Small in scale yet rich in significance, such moments can leave a lasting psychological impact.

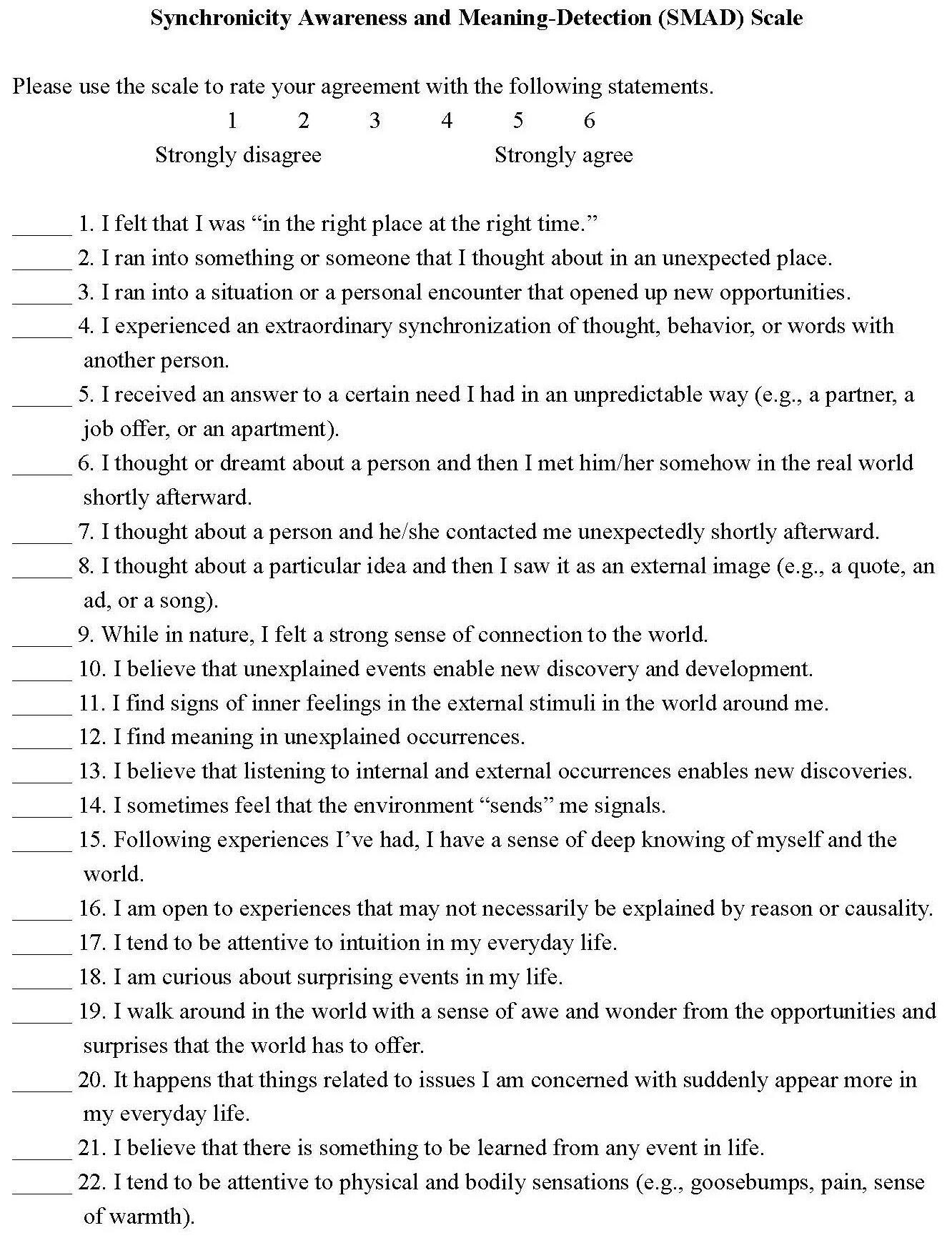

The Synchronicity Awareness and Meaning-Detection (SMAD) Scale (Russo-Netzer & Icekson, 2023)

To explore this, we developed the REM Model (Russo-Netzer & Icekson, 2023):

Receptiveness: Being open and mindful to inner and outer experience.

Exceptional encounter: An unexpected, emotionally resonant event.

Meaning-Detection: Reflective interpretation that creates coherence.

Crucially, our studies found that synchronistic events often emerged during periods of transition—such as following loss, during relocation, or when facing major life decisions. In these liminal moments, when familiar structures were unsettled, such occurrences frequently served as symbolic “trail markers,” guiding individuals toward a particular insight or direction. Participants perceived them not as random, but as infused with personal meaning.

Quantitatively, using the Synchronicity Awareness and Meaning-Detection (SMAD) Scale, we found that individuals higher in openness to experience and self-reflection were significantly more likely to notice and interpret these events as meaningful. This finding reflects William James’s (1890/1950) assertion that what we pay attention to makes all the difference (“my experience is what I agree to attend to,” p. 402). Synchronicity, then, is not a matter of pure chance, but rather a meeting point between the inner and outer worlds—what Martin Buber (1970) described as “All real living is meeting.”

What William James and Martin Buber bring light to, is that these experiences remind us that meaning is not always planned or logical, it is an experience we voluntarily agree to meet. This allows for us to heed the whisper of meaning in the unexpected, as Marcel Proust observed, “the real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

Opening Up to Our Senses: A Tangible Path to Meaning

Meaning can also be awakened through a far more immediate, embodied channel: the human senses. In a recent study with 188 adults (Russo-Netzer & Atad, under review), participants were randomly assigned either to a sensory-based meaning intervention or to an active control group. Those in the sensory group recalled a personally meaningful memory anchored in one of the five senses—such as the scent of a grandmother’s orange cake, the sound of a childhood melody, or the feel of sea air on the skin—and to reengage with that sense through a new, self-chosen activity during the following week.

This simple sensory reconnection yielded significant psychological benefits. Participants experienced greater subjective well-being, enhanced self-insight, increased hope, and a stronger orientation toward meaning-driven action in daily life. Importantly, they also reported a reduction in symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress.

These findings highlight the senses not merely as conduits of pleasure or mindfulness, but as embodied gateways to existential depth. Sensory experiences often bypass intellectual defenses, allowing individuals to access dormant memories, values, and sources of vitality. They reconnect us to our personal narratives and offer an anchor in the present—especially critical during moments when life feels unmoored or overly abstract.

In this light, the scent of rain, the texture of familiar fabric, or the first taste of a seasonal dish are not trivial details; they are portals to significance. Our study invites a rethinking of meaning-making as not only a cognitive or reflective endeavor, but one that is deeply rooted in the body’s capacity to notice, feel, and remember. Especially in turbulent times, when the world feels abstract or overwhelming, the senses can serve as quiet messengers of continuity and connection.

Stretching Toward the Unknown: The Power of Small Acts of Courage

Uncertainty holds the potential to expand individuals' perspectives and illuminate pathways to authenticity and meaning. This raises a compelling question: what occurs when individuals deliberately engage with uncertainty through intentional behavior, actively stepping beyond familiar routines? To explore this, we invited 156 adults to take part in a two-week study in which they engaged once a week in a “behavioral stretch”—a small, self-chosen action that felt slightly uncomfortable or unfamiliar. Examples ranged from initiating a difficult conversation to trying a new activity or offering unexpected help to a stranger (Russo-Netzer & Cohen, 2023).

Clockwise from top left: Lewis Carroll and Disney’s 1951 adaptation of Alice in Wonderland; L. Frank Baum and a black and white and technicolor still from The Wizard of Oz (1939).

Quantitative pre- and post-intervention measures assessed meaning in life, well-being, self-efficacy, and openness to experience, while qualitative reflections captured participants’ subjective experiences. The findings revealed a powerful insight: among participants who reported low life satisfaction at the outset, even brief intentional acts of stepping beyond their comfort zone led to significant improvements in well-being. Importantly, it wasn’t the novelty of the action that mattered most, but the meaning behind it. When participants chose discomfort in the service of their values—whether connection, courage, contribution, or authenticity—the stretch became a source of affirmation rather than threat.

Many participants described initial fear and hesitation, followed by a sense of expansion, pride, and even surprise at discovering new facets of themselves. As one shared: “I didn’t think I could do it. But I did. And now I know I’m capable of more than I thought.”

In this light, the comfort zone is not just a psychological boundary—it is a symbolic threshold between the familiar self and the possible self. Choosing to cross it, even gently, is an act of existential courage: a way to meet the anxiety of uncertainty not with avoidance, but with openness and intention. When we stretch ourselves—leaning into the discomfort of not knowing—we create conditions for something new to emerge: a more integrated self, a restored sense of agency, and deeper alignment with what truly matters.

This echoes a deeper narrative found in some of our most enduring stories. Think of Alice, whose tumble down the rabbit hole in Wonderland disorients her but leads her to question assumptions and perceive reality in new ways. Or Dorothy, swept from the grayscale of Kansas into the vibrant unpredictability of Oz. In each, disorientation is not the end—it is the beginning. The unfamiliar becomes a gateway to insight, and the courage to move through confusion becomes the path to clarity.

Likewise in life, when we stretch beyond the known—our habits, perceptions, and routines—we don’t just discover new behaviors. We begin to redefine what matters most. We move from passive existence to intentional engagement, uncovering the quiet, luminous beauty of becoming more than we imagined.

Prioritizing Meaning: From Intention to Daily Practice

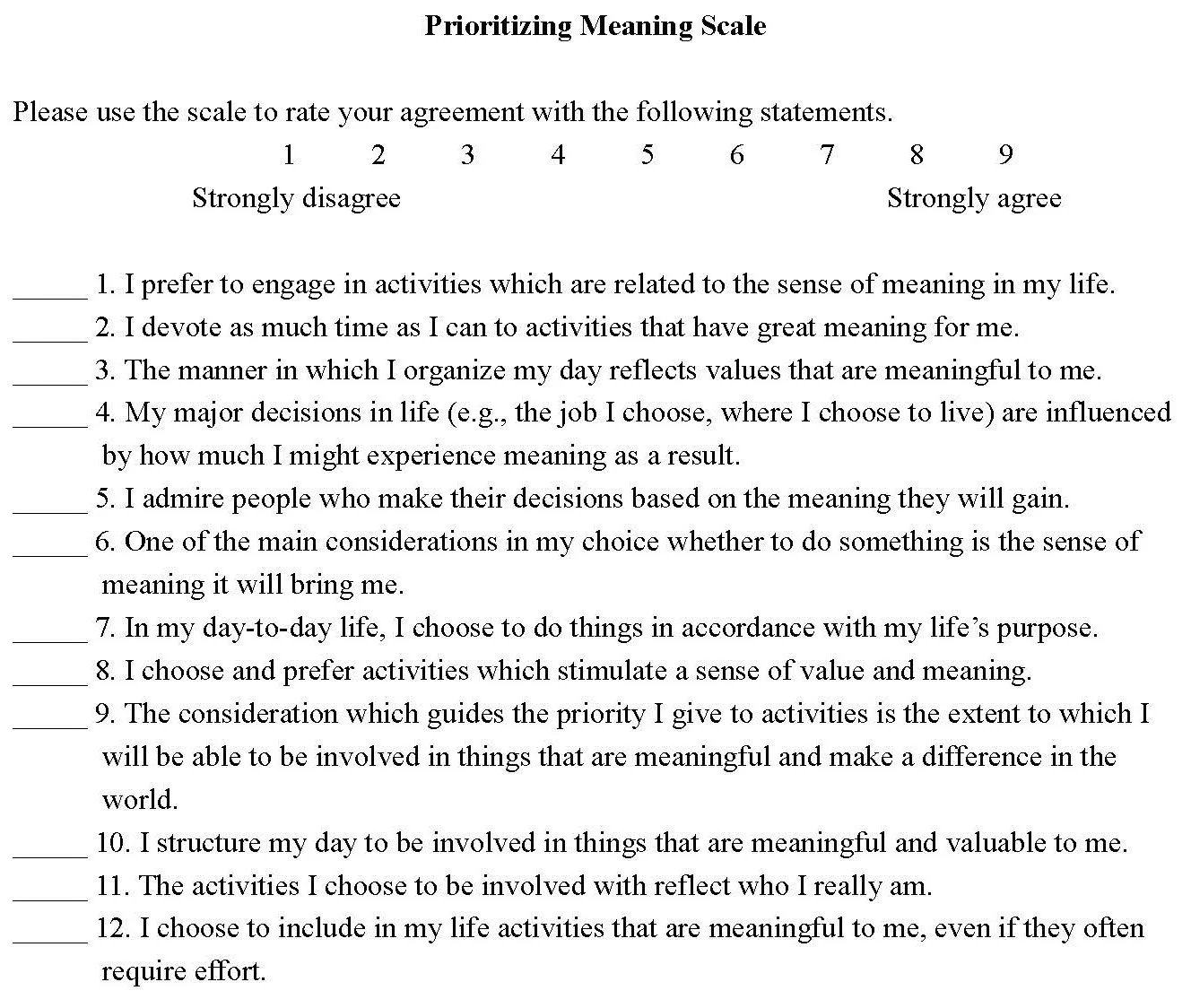

The Prioritizing Meaning Scale (Russo-Netzer, 2019).

While stepping outside one’s comfort zone may serve as a catalyst for personal growth, sustaining a meaningful life requires more than occasional leaps—it calls for consistent, intentional structuring of one’s daily life around what truly matters. This is the essence of prioritizing meaning: not merely seeking profound experiences, but deliberately integrating meaning into everyday routines.

To explore this idea empirically, I developed the 12-item Prioritizing Meaning Scale (Russo-Netzer, 2019), which assesses the extent to which individuals organize their days around value-driven activities. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) and include statements such as, “The manner in which I organize my day reflects values that are meaningful to me." Higher scores were associated with greater engagement in activities such as caring for others, volunteering, or pursuing creative projects—even when these required effort or personal sacrifice.

Across several studies (Atad & Russo-Netzer, 2022; Russo-Netzer, 2019; Russo-Netzer & Shoshani, 2020; Russo-Netzer & Atad, 2024), we found that individuals who made deliberate efforts to prioritize meaning in their everyday lives reported higher levels of well-being, vitality, emotional richness, and a deepened sense of coherence. These individuals weren’t merely searching for meaning as an abstract concept—they were actively enacting it in their choices, relationships, and daily routines.

This consistent alignment between inner values and outward behavior emerged as a stabilizing and energizing force—particularly in a world characterized by overstimulation, uncertainty, and constant distraction. Importantly, the research revealed that meaning is not a passive occurrence or a sudden revelation, but something that grows through intentional, value-consistent actions—how we plan our days, how we show up for others, and how we continually respond to the question, “Why is this important to me?”

In this way, prioritizing meaning is not about waiting for a grand revelation, but about engaging deliberately with the ordinary moments of life—choosing what to care about, and allowing those choices to shape how we live. It is a daily act of anchoring ourselves in what matters most, especially amid uncertainty.

And yet, the way we recognize, pursue, and live out meaning is not universal. The paths to meaning are shaped not only by personality or values, but also by the cultural worlds we inhabit and the life stages we traverse. What one considers meaningful in adolescence may shift dramatically in adulthood or later life. Similarly, the very definition of a "meaningful life" may differ across societies, belief systems, and historical contexts.

Expanding the Lens: Developmental and Cross-Cultural Dimensions of Meaning

When exploring how people create meaning in their lives, a fundamental question arises: Is the experience of meaning shaped by our age, gender, and culture? In collaboration with colleagues, I examined this question using data from over 23,000 individuals across more than 100 countries (Russo-Netzer, Niemiec, & Tarrasch, 2023). We focused on three core components of meaning in life: coherence (the sense that life makes sense), purpose (being guided by meaningful goals), and mattering (feeling that one’s life is significant and valued).

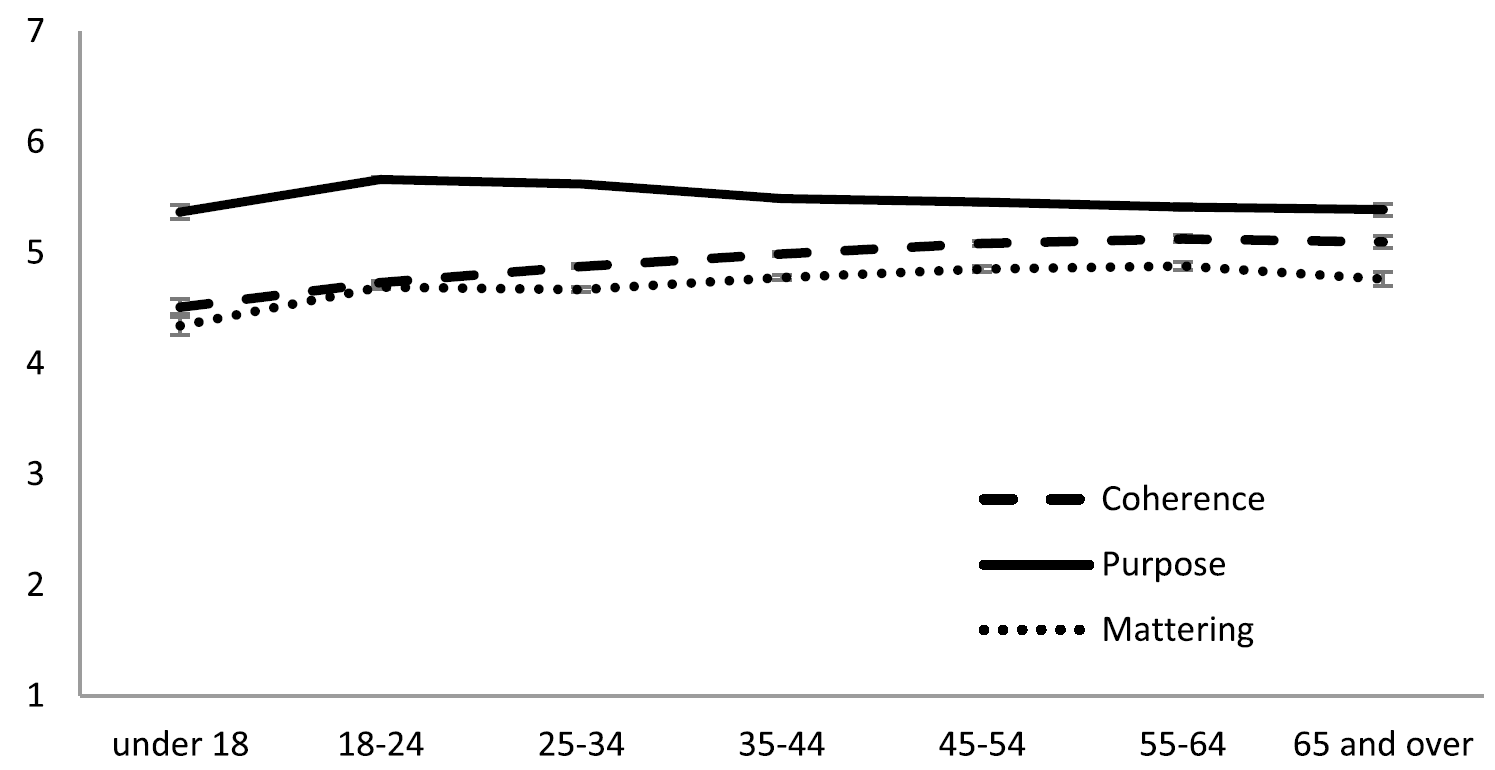

Each of the three meaning components, by age (Russo-Netzer, Niemiec, & Tarrasch, 2023).

Our findings revealed clear developmental patterns. Coherence steadily increased with age—perhaps reflecting the accumulation of life experience and deeper sense-making over time. Purpose peaked during early adulthood, when people tend to shape their identity and pursue goals, and then declined gradually through midlife. Mattering followed an inverted-U-shaped curve: lowest during youth and late adulthood, and higher during the middle years. This may reflect shifting social roles and changes in perceived social impact across the lifespan.

Gender differences were also notable: men reported higher coherence, while women consistently reported higher levels of mattering—possibly reflecting gendered socialization toward cognition versus connection. Interestingly, no gender differences emerged for purpose.

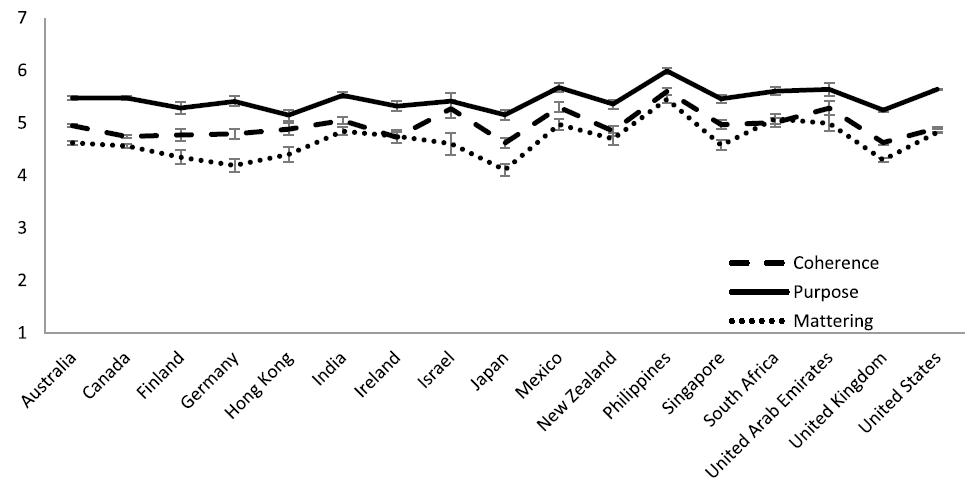

Each of the three meaning components, by nation (Russo-Netzer, Niemiec, & Tarrasch, 2023).

Cultural differences added further nuance. People in collectivist cultures—such as the Philippines, Mexico, and the United Arab Emirates—reported higher overall levels of meaning in life than those in more individualistic societies like the U.S., U.K., and Finland. These findings suggest that in more collectivist contexts, meaning may be grounded in social harmony, family ties, and community contribution. In contrast, individualistic cultures may emphasize personal growth, autonomy, and self-actualization.

And yet, across all countries, ages, and identities, one common thread emerged: the deep human need to matter. Whether through raising children, contributing to a cause, or simply being present for others, people expressed a shared desire to feel that their lives count. This longing for significance may be the emotional heartbeat of meaning, reminding us that, no matter how diverse the paths we take, the wish to be of value—to someone, to something—unites us all.

But how do we access and express our unique potential to contribute, to connect, and to matter?

Character Strengths as Gateways to Meaning

One powerful entry point lies within ourselves: our character strengths. These inner resources—such as curiosity, kindness, bravery, or perseverance—serve not only as reflections of who we are, but as pathways to who we might become. When activated with intention, character strengths can become bridges between our values and our actions, helping us live more meaningfully and authentically.

To deepen our understanding of how people construct meaning across cultures, we turned to the science of character strengths—positive, morally valued personality traits that are relatively stable over time and contribute to personal and collective flourishing. These include traits such as gratitude, curiosity, kindness, hope, and spirituality.

Using data from a large international sample across 28 countries, we explored how specific character strengths contribute to the three dimensions of meaning: coherence, purpose, and mattering (Russo-Netzer, Tarrasch, & Niemiec, 2023). Participants completed validated self-report questionnaires and responded to open-ended questions that invited them to reflect on and describe their personal experiences with character strengths in daily life.

Quantitative analyses revealed meaningful associations: hope and spirituality emerged as strong predictors of purpose, while gratitude and kindness were linked to mattering, and curiosity and perspective supported a sense of coherence. These connections were not merely statistical—they were vividly illustrated in the personal narratives participants shared.

A woman from Brazil, for instance, described how cultivating gratitude helped her remain connected to meaning even in the face of illness. A young man from India reflected on how his curiosity reframed personal failures as steppingstones, giving greater coherence to his life story. These stories echo a broader insight: character strengths are not just attributes—we can think of them as pathways to meaning. They serve as inner resources we can draw upon to interpret our experiences, to navigate uncertainty, and to bridge the gap between who we are and who we aspire to become.

In times of ambiguity and transition, character strengths can help us stay grounded in what matters most—while pointing the way forward. They help us ground our values in action, infuse daily experiences with coherence, and foster a sense of contribution and connection. When activated intentionally, these strengths serve as internal compasses—especially during times of uncertainty—guiding us toward meaning that is not only felt, but enacted.

From Potential to Practice: An Integrative Model of Meaning in Life

"We are all just a car crash, a diagnosis,

an unexpected phone call, a newfound love,

or a broken heart away from becoming a completely different person.

How beautifully fragile are we that so many things

can take but a moment to alter who we are forever?”

― Samuel Decker Thompson

These unexpected and transformative moments are the essence of living meaningfully. Meaning is a dynamic process—shaped, dismantled, and rebuilt by life’s unpredictability. Disruption, wonder, and choice invite us to reexamine who we are, what we value, and what truly matters. This feature explored diverse doorways to meaning: existential anxiety as a catalyst, the courage to stretch beyond comfort zones, the serendipity of synchronicity, the prioritization of values, the anchoring role of character strengths, and the shaping influence of culture and development.

In this view, meaning is an evolving relationship between the self, others, and the world—unfolding through reflection, responsiveness, and committed action. Cultivating it is not a luxury but an existential imperative, embracing discomfort as part of transformation. As Nietzsche wrote, “One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.” Meaning emerges not in spite of life’s fractures, but through them.

To live meaningfully is to loosen the grip of outdated narratives, welcome what truly matters, and remain open to life’s invitations. It rests not on certainty, but on the courage to ask, to feel, and to change—discovering not only who we are, but who we are becoming.

Pninit Russo-Netzer, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor, senior lecturer, author, speaker, and researcher. She is deeply passionate about building bridges—across disciplines and between theory and real-life practice—in therapy, organizations, communities, and education across the lifespan. She heads the Community, Meaning, and Healing (C.M.H.) Research and Development Institute as well as the Resilience and Optimal Development Lab at Achva Academic College. Her primary research and practical interests focus on meaning in life, existential psychology, spirituality, positive psychology, post-traumatic growth, character strengths, and processes of positive change and growth. Prof. Russo-Netzer is the founder and director of the Compass Institute for the Study and Application of Meaning in Life and head of the Academic Training Program in Logotherapy (meaning-oriented psychotherapy). She serves as an academic advisor and consultant to institutions and organizations worldwide—including the World Trade Center Health Registry (WTCHR) and the Global Youth Meaningfulness Index (YMI) Advisory Council. She is the recipient of the Spirituality and Meaning Researcher Award from the International Positive Psychology Association (IPPA) and the Early Career Award from the International Society for the Science of Existential Psychology (ISSEP). Prof. Russo-Netzer is an Associate Editor at Current Psychology and has published numerous academic articles and book chapters. She is the co-author and co-editor of several books, including Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology (Springer), Clinical Perspectives on Meaning: Positive and Existential Psychotherapy (Springer), Existential Authenticity (Springer), and Finding Meaning: An Existential Quest in Post-Modern Israel (Oxford University Press), among others.