Optimizing free will: Goal self-concordance and goal breakthrough models

University of Missouri. August 12, 2025.

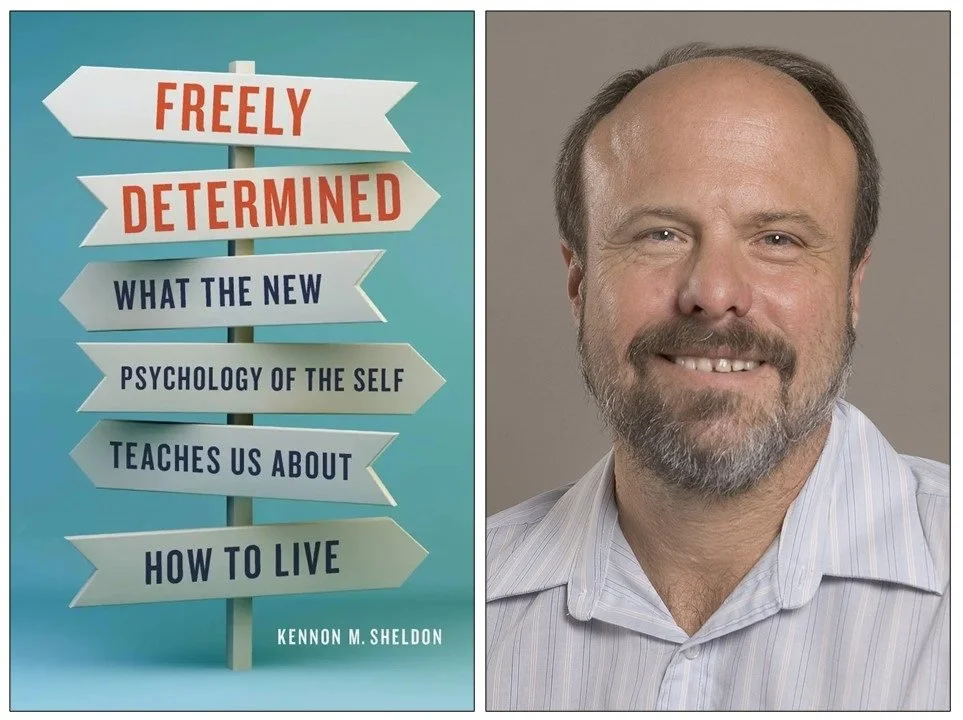

Kennon Sheldon and his book, Freely Determined (2022).

I’ve long been drawn to questions about human choice. Are we truly in control of our actions, or are we just following patterns laid down by our habits, our upbringing, or even our biology? If we do have real control, how does it work and how well do we actually use it?

I study how people make decisions and pursue goals, with the aim of predicting behavior. But that leads to a strange question: if we can predict someone’s choices, were they really making a choice at all? Or were they just acting out an involuntary script? To me, real choice involves something more. It happens in moments when we stop, reflect, and come up with something new: a creative leap, an unexpected idea, a solution that no one saw coming. These moments feel like they come from nowhere. But that raises another question: could even those brilliant, original thoughts have been predicted too? Were they somehow always going to happen? Questions like these continue to shape my thinking.

Blending Evolutionary, Humanistic, and Existential Ways of Thinking

I’ve typically thought of my work as grounded in two key ideas. The first comes from humanistic psychology, which holds that people are naturally motivated to grow, thrive, and fulfil their potential, especially when they’re treated with care and respect. The second comes from evolutionary thinking. This drive to grow and self-direct did not appear out of nowhere; it developed over time, shaped by the demands and opportunities of our evolutionary past. In other words, people are built to thrive, but only when their environment supports it.

In recent years, I’ve also started thinking about my work in existential terms. That shift began as I explored the question of how we can best use our free will, a theme I focused on in my book, Freely Determined (2022). If free will exists, then the next question is how to use it well. How can we make choices that produce lives that are not just successful, but also meaningful, fulfilling, and even sublime? What I concluded is: no matter what our situation, it’s still up to us to make the best of it. This ability to choose and direct our lives, is at the heart of existential thought.

Starting at the beginning: As a psychology major at Duke University in the late 1970s, I ended up in the artsy-hippy dorm, where there was a lot of inner exploration going on. For my senior research project I studied the cognitive psychology of music, especially how people perceive melody. I was also playing piano, and began to write songs, which gave me a creative outlet to explore those same questions outside the classroom. Some of those songs, particularly the existentially themed ones like Last Day, Sleeping Spell, Earth Elegy, Beginning of Time, Terror’s Children, Standing on the Edge, and Empath, can be found here.

At the same time, I was drawn to deeper questions about human potential. I read widely: religious writings from Yogis, mystics, and Zen masters; the humanistic psychology of thinkers like Abraham Maslow, Rollo May, and Carl Rogers; the existential ideas of Sartre, Frankl, and Kierkegaard; and the psychedelic explorations of Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ken Kesey. I wanted to understand what “enlightenment” meant, and how a truly enlightened person might live.

After graduation, in the early 1980s, I moved to Seattle, where I worked in group homes and played in several bands. In 1984, I began studying existential-phenomenological psychotherapy at Seattle University. Coursework included classic texts by Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Levinas, and Heidegger, which deeply influenced how I approached questions about meaning and experience. I also took part in Werner Erhard’s training (Erhard Seminar Training, EST), a popular self-improvement seminar of the era. It drew loosely on ideas from Zen Buddhism and focused on shifting how people experienced their lives. The idea was that problems people had been struggling to change, or simply putting up with, might be resolved through a fundamental change in perspective. It made me realize I was responsible for what happened to me and that I could shape my life by committing to meaningful goals I chose to live by.

Control, Happiness, and Choosing Goals

Eventually I gave up on a music career and entered a Ph.D. program in personality psychology at UC Davis (1986-1992). There, I worked with Bob Emmons, who taught me how to rigorously think about people’s personal goals and strivings. I was strongly influenced by Carver and Scheier’s (1982) control theory, which proposes that our personalities are shaped in large part by the goals we choose for ourselves, especially the broader, longer-term goals that sit higher in our internal hierarchy of motivations, like “be a forgiving person” or “finish whatever I start.” I was drawn to this model because it suggested that people have real agency. We’re not just the sum of our habits, instincts, or past experiences. We can steer our lives with purpose and direction, via our self-endorsed “big goals.”

I also became interested in happiness and well-being, which was a major focus for Bob Emmons. Bob had studied with Ed Diener, social psychology’s “happiness guru,” which, I suppose, makes me his academic grandson (as Ed himself said to me). I was especially curious about how setting personal goals might offer a direct and intentional way to pursue happiness. It also struck me that changes in well-being could be a meaningful way to measure how well a person’s efforts were working. If we’re doing something that is worthwhile, it should feel good and rewarding. If not, then it’s worth asking whether we’re putting our time and energy in the right places. These questions made me wonder: can people predict which goals will bring lasting happiness and growth, or do we often get it wrong? If some goals are better for us than others, can we learn to recognize and commit to them?

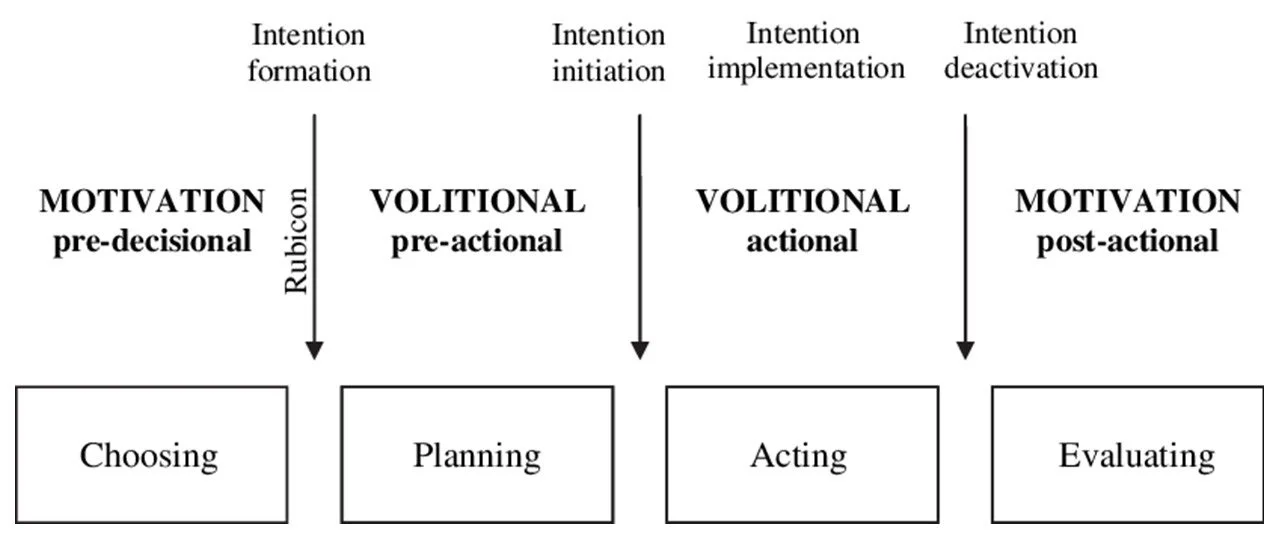

As I continued my graduate work, I began to notice something missing in the field of motivation science. Researchers had explored how people pursue goals: how they plan, act, and evaluate their progress, but said surprisingly little about how people choose their goals in the first place. That gap caught my attention. For example, Peter Gollwitzer’s Action Phases Model (Gollwitzer, 1990), widely accepted still, divided goal pursuit into four stages: deliberation (choosing what to do), planning (figuring out how to do it), action (carrying it out), and evaluation (reflecting on the outcome). But most of the research focused on the middle three stages. Deliberation, that is deciding what goals to pursue, had been little studied.

Clockwise from left: Yorick's skull in Hamlet’s 'gravedigger scene' (5.1), depicted by Eugène Delacroix; Dr. Fausto by Jean-Paul Laurens; Richard Mansfield as Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Gollwitzer described deliberation mostly in terms of expectancy-value theory: people choose the option they both want and believe they can attain. But that view seemed overly rational and tidy. In my own life, and in conversations with others, choosing what to strive for often felt confusing, conflicted, even painful. The great literary dilemmas such as Hamlet's paralysis, Faust's ambition, and Jekyll's divided self are not driven by simple cost-benefit calculations. They are shaped by uncertainty, doubt, and deep existential questioning. That, to me, is where the real action is. I explored these ideas further in an NPR Hidden Brain episode which resonated with many listeners. Clearly, I wasn’t the only one asking these questions.

After completing my Ph.D., I began a postdoctoral fellowship in 1992 at the University of Rochester with Ed Deci and Rich Ryan. There, I became fascinated by self-determination theory’s relative autonomy framework (Ryan & Connell, 1989), which showed that people’s reasons for acting vary in how self-directed they are. Some goals reflect autonomy, pursued out of interest or personal value. Others feel controlled, driven by pressure or obligation. This distinction helped clarify how motivation influences well-being and behavior. I was the first to apply this framework to people’s own self-generated goal statements. To my surprise, many people reported pursuing life goals they neither wanted nor liked. How could this be? Why does it happen?

The Concept of Self-Concordance

It was during my time at Rochester that I began developing the concept of “self-concordant” goal pursuit. I later refined and strengthened this idea in my early years as an Assistant Professor at the University of Missouri in the late 1990s. Self-concordance occurs when people have made good choices, symptomized by strong internal rather than external locus of causality for their goals and actions, meaning they feel true ownership of their goals. The idea is that, even if people don’t always know exactly what they want, they can usually tell how they feel about the goals they think they want. A low self-concordance score means someone has chosen goals that don’t really match their deeper interests, values, or natural tendencies. When this happens, it might be a sign to rethink those goals. On the other hand, high self-concordance means a person has picked goals that fit well with their true self. Supporting this idea, experiments where people were randomly assigned goals that didn’t suit their measured personalities showed lower self-concordance scores, confirming that mismatched goals feel less authentic.

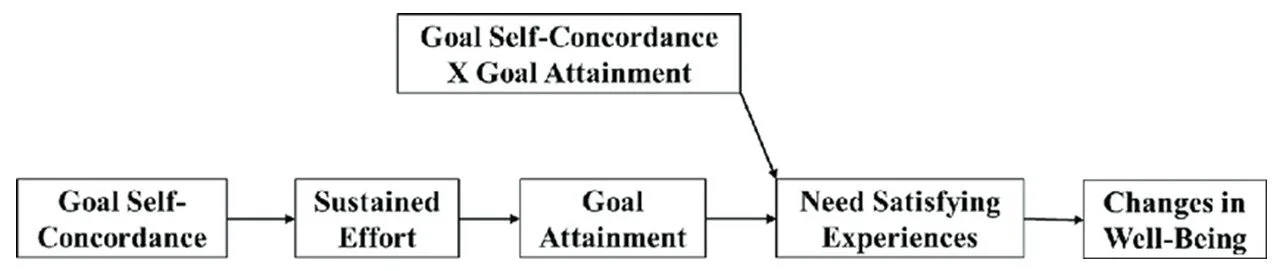

A diagram of the original self-concordance model (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999).

According to the original self-concordance model (Sheldon & Elliot, 1999), people who select goals that align with their deeper values and interests are more likely to invest sustained effort in pursuing them. That effort increases the chances of success. When people achieve goals that genuinely reflect who they are, the experience brings a strong sense of psychological need satisfaction, which in turn leads to greater well-being.

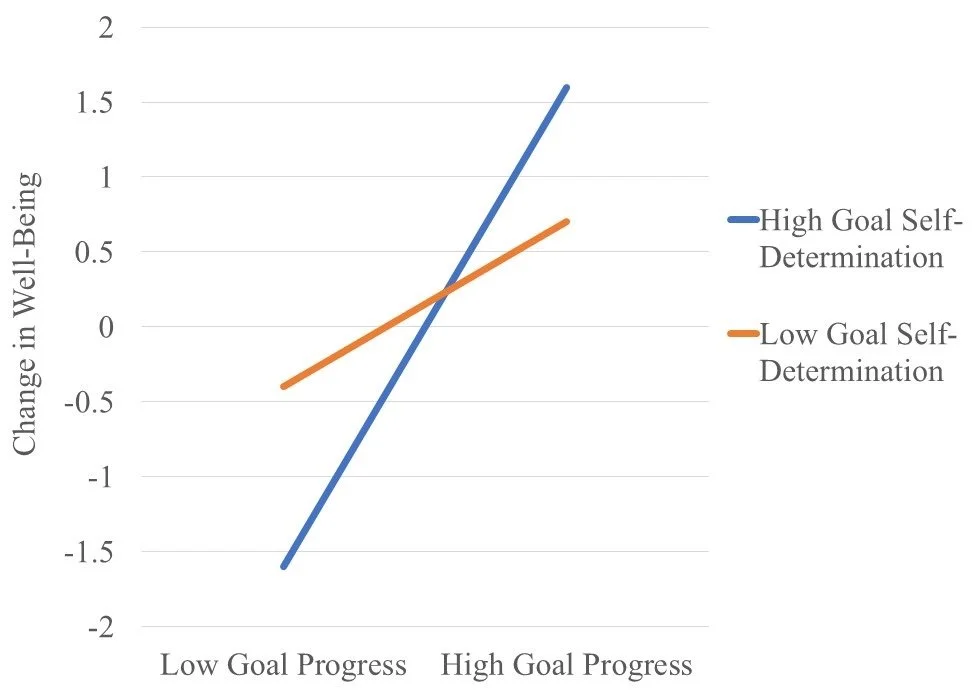

Data pattern from Sheldon & Kasser (1998) suggest that making progress toward self-determined goals tends to bring a bigger boost in satisfaction and happiness.

This model highlights two important benefits of pursuing self-concordant goals. First, it helps people stay committed to their goals over time. That means your New Year’s resolutions are more likely to stick past January. Second, self-concordant goals make success more emotionally rewarding. When you truly care about a goal, achieving it tends to bring a bigger boost in satisfaction and happiness. The graph illustrates this pattern. It shows that reaching goals that are not self-concordant has little or no effect on well-being, while achieving self-concordant goals leads to a significant increase in happiness. The graph reveals a downside. Failing to reach a self-concordant goal can sometimes leave you feeling worse than before. In other words, it can be risky to go after what you really want, even though your deeper mind will likely help you get it.

Why do people choose goals that don’t really fit them? I came to believe that one key reason is a disconnect between our conscious thinking and our deeper, less conscious motives. People often don’t know what they truly want. This is a problem because we’re free to choose and announce goals that we don’t actually care about. In a 2014 review article, building on Daniel Kahneman’s (2011) work, I suggested that setting goals depends on deliberate thinking and verbal expression. But as motivation researchers have known for decades, our consciously stated goals don’t always match our underlying drives (McClelland et al., 1989). For example, a person might think they care most about achievement, when deep down they value close relationships more. Or they might see themselves as a warm, social person who values connection, when in fact they’re driven more by a need to outperform others and prove their superiority. These mismatches can lead people to choose goals that don’t reflect who they really are. And because we often stick with our goals for years, the emotional costs of this misalignment can be high. Some people spend decades chasing goals that bring little meaning or satisfaction.

Beyond Stuckness to Breakthroughs

Although the self-concordance measure diagnoses the condition of non-congruent goal-striving, it provides no advice concerning how we can overcome this condition. My most recent research directly addresses this question by emphasizing the role of conscious agency in revising our goals. The Goal Breakthrough Model, which I’ll outline below, sees goal selection as a creative and evolving process—one that blends careful reflection with flashes of insight from the deeper, non-conscious parts of our mind. This idea builds on classic thinking from nearly a century ago (Wallas, 1926), and it remains relevant today in creativity research (Cropley, 1997; Helie & Sun, 2010, 2015), which highlights how breakthroughs often arise from the dance between focused thought and spontaneous inspiration.

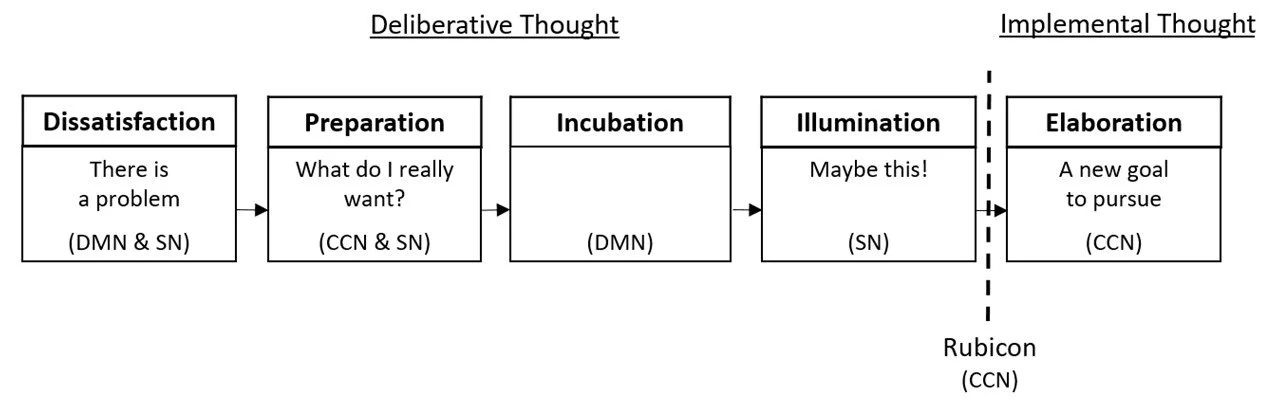

In essence, the Goal Breakthrough Model replaces the single “deliberation” phase in Gollwitzer’s Action Phases Model (discussed above) with a much more detailed sequence of four sub-phases, each linked to activity in different brain networks (Sheldon et al., 2024). It starts with recognizing dissatisfaction with the status quo. This happens during a free-thinking phase, driven by the brain’s default mode network, which is active when our minds wander and reflect. This network helps us locate when something isn’t quite right in our lives. Next comes preparation, where we begin focusing our attention and asking ourselves important questions like, “What do I really want? What can I do about this?” This stage involves two brain systems working together: the cognitive control network, which helps us concentrate and plan, and the salience network, which flags important thoughts and feelings that deserve our attention.

A diagram of the Goal Breakthrough Model (Sheldon et al., 2024).

After preparation, the mind moves into incubation. This is a quiet period where the cognitive control network steps back, and the default mode network works behind the scenes, making connections and exploring new possibilities without our conscious effort. Then, the salience network helps bring any meaningful new insights to conscious awareness, leading to the “aha” moment. This is the sudden realization or breakthrough that helps one cross the metaphorical Rubicon. Finally, the cognitive control network takes charge again to turn that insight into a clear goal and guide us through planning, action, and evaluation as we work to make the change happen. Together, these brain networks take turns supporting us as we move from feeling stuck to creating powerful new goals and meaningful progress.

Sheldon and colleagues (2023) tested the Goal Breakthrough Model in two self-report studies. In one study we asked people to recall a time when they figured out what they really wanted to do in life. For example, switching careers, ending a relationship, or deciding to go back to school. In another study we guided participants to work toward a real breakthrough in the moment. In both studies, people described what they were thinking at the beginning, middle, and end of the process. The results supported a three-step path: stronger conscious reflection (“What’s missing in my life?” or “What do I really want?”) was followed by a more active nonconscious phase, when ideas were simmering in the background. This then led to a more profound insight or “aha” moment, like realizing “I want to be a teacher,” or “It’s time to move on.” The stronger this insight felt, the more people reported feeling like a more unified person, with greater well-being and a clearer sense of purpose.

Free Will, Symbolic Self, and Existential Courage are Key to Goal Breakthroughs

The Goal Breakthrough Model also connects to how we think about free will. In a philosophical view known as compatibilism, free will is the ability to choose between different possible courses of action. The model captures this idea by showing how we first engage the non-conscious mind to generate creative possibilities and then consciously select among them. In other words, it offers a way to understand how free will operates, blending spontaneous insight with deliberate decision-making.

How do we influence the process described by the Goal Breakthrough Model to create our own breakthroughs? To answer this, I draw on the concept of the symbolic self. This is a higher-level sense of “being me,” the experience of owning and directing one’s life. This self is not just a passive observer but acts like an internal executive, overseeing and guiding the mental processes involved in goal formation and change (Skowronski & Sedikides, 2019).

The symbolic self plays a crucial role at several key moments in the goal breakthrough journey. First, it initiates the preparation phase by posing important, reflective questions such as “What do I really want?” or “What feels wrong about my current path?” These questions prime the mind to search for new possibilities. Next, when fresh insights or “aha” moments arise from the unconscious workings of the mind, it is the symbolic self that recognizes and endorses these ideas, deciding which ones feel authentic enough to become new goals. Finally, the symbolic self is responsible for maintaining focus and motivation as we move forward. This transforming insights into concrete plans and sustained actions. In this way, it acts as a steady captain, navigating the sometimes-turbulent waters of change by continually steering our thoughts and behaviors toward the goals we have chosen.

However, uncovering goal breakthroughs is not always easy, because the symbolic self serves other important functions beyond simply managing action. One of its key roles is defensive: it works to reduce internal conflict, preserve the current self-image, and manage anxiety about change. This protective tendency means the symbolic self may resist asking the hard questions that prompt new insights, or hesitate to fully embrace new goals, even when promising possibilities emerge. This tension leads to a central insight: moving toward meaningful growth and authentic change requires a special kind of courage, which I call existential courage. Existential courage is the willingness to face the sometimes-uncomfortable truth about ourselves in order to make decisions that truly serve our growth and well-being.

The courageous person is able to: (1) Acknowledge feelings of dissatisfaction, which can be unsettling; (2) Explore those feelings with hard and honest questions; (3) Pay attention to the new thoughts and insights that arise, despite their uncertain implications; (4) Clearly articulate new goals based on this awareness, even if one is not sure one can get them; and (5) Commit time, energy, and resources to pursuing those goals, with no bullshit. In EST terms, we take a bold stand, then really live out of it. Existential courage empowers us to harness the full power of the Goal Breakthrough Model.

Ultimately, while our conscious selves are inherently subjective, they possess a clear and objective power: the ability to guide our minds and brains toward genuine happiness and well-being. Exercising this power requires courage and bravery. But shouldn’t a meaningful life require this? Nobody said it would be easy.

Kennon Sheldon is a professor of Psychological Sciences at the University of Missouri, USA. He received his B.S. in psychology from Duke University in 1981 and his Ph.D. in social/personality psychology from the University of California, Davis in 1992. He is known for his research on happiness, motivation, and goals. His prominent research questions include “Can happiness go up, and then stay up?”, “Are people able to pick life-goals that better express their true desires and deeper potentials?” and “how can the concept of personal agency be reconciled with the concept of a deterministic universe?” He is the prolific author of more than 300 academic articles and book chapters. He is also the author of Freely determined: What the new psychology of the self teaches us about how to live (2022) and Optimal Human Being: An Integrated Multi-level Perspective (2004), and has edited several other academic books such as Designing Positive Psychology: Taking Stock and Moving Forward (2011) and Stability of Happiness: Theories and Evidence on Whether Happiness can Change (2014). He has received several prestigious prizes and awards in psychology, and was named one of the 20 most cited young social psychologists in 2010 (Nozek et al., PSPB).