Grace Hart on Death Concepts and Modeling Suicide Risk

Frances Grace Hart is a post-baccalaureate lab manager at Yale University in Dr. Shirley Wang’s Computational Clinical Science Lab. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in Psychology with a minor in Philosophy from Boston College in 2023. Her research is primarily focused on understanding what people think and feel about death (i.e., death concepts) and how these contribute to suicide risk. To do so, she employs computational techniques, such as natural language processing. In the near future Grace will apply for admission to PhD programs in clinical psychology—during which she hopes to expand her work to include timeseries designs and formal modeling of death concepts and their psychological impacts. Grace’s work is guided by her metascientific interests in theory building and measurement, and her commitment to one day develop existentially-informed, scalable interventions for suicide.

Grace on the web: Website on Github | Lab Page | Google Scholar | Twitter

By Emily Courtney, University of South Florida. August 20, 2025

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and the science of existential psychology?

Grace Hart: I grew up in a deeply religious household. For a long time, that religious framework gave me comfort and structure around big questions like what it means to be a good person, or what happens when we die. But, like many people, by the time I reached my teenage years, the explanations offered by my religious community started to feel unsatisfying.

So, it was around then that I began searching elsewhere for better explanations. That was when, completely by accident, I discovered philosophy. I didn’t grow up in a household where anyone was reading philosophy, or probably even knew what philosophy was, so I learned about it by bumping into it out on a YouTube channel called The School of Life. That channel had all these cute little snippet videos on various topics, and one of their videos was about existentialism, and I remember thinking: “This is it—these are the questions I care about!” From there, I started reading authors like Camus, Sartre, and Kierkegaard. I will say, I never felt empty. It simply felt as though I had switched from one food to another; it was a nice transition, in terms of both being intellectually stimulating and addressing my needs on a deeper personal level.

Eventually, when I got to college, I learned that there was a whole branch of psychology called existential psychology. That was really an important moment, because although I loved philosophy I was looking for ways to translate abstract philosophical ideas into tangible psychological principles that could be applied to help alleviate suffering in daily life. I immediately recognized existential psychology as this really natural synergy between philosophy and psychology, so I gravitated toward that and it continues to guide my work.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research in existential psychology lately. Can you tell us more about your work?

Grace Hart: Absolutely! I am currently working as a post-baccalaureate research supervisor at Yale in Dr. Shirley Wang’s Computational Clinical Science Lab. Our work is focused on being able to better identify Who is most at risk for suicide, and when?

We do have a good understanding of many lifetime risk factors for suicide, things like trauma, genetics, minority stress or socioeconomic burden. But those things just tell us about overall lifetime risk. We still struggle to predict short-term time-sensitive risk. If someone presents at a clinic with suicidal ideation, it’s still really difficult to accurately predict whether or not that person is actually going to go on to attempt later that day or that week; and it’s even more frustrating because many people who attempt suicide see a healthcare provider within a month beforehand. So, they’re coming into contact with us yet we still can’t reliably determine who’s at immediate risk.

So, to try make progress in that direction we’re using computational approaches, analyzing large idiographic datasets to model personalized suicide risk on an imminent timescale—same day, or next day, or that week. One way we’re doing this is through ecological momentary assessment (EMA); participants download an app and multiple times a day, for a period of six months to a year, they complete surveys about their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. We ask how they’re feeling about themselves and their lives; if they thought about suicide or self-harm that day; if they attempted suicide or self-harm; and lots of other really granular data. Our goal is to build predictive tools that clinicians can use to better know when to deploy just-in-time interventions and in-the-moment support when it’s needed most.

I’m also deeply interested in what people believe happens when they die, and how that shapes suicide risk. Many theories of suicide view it as a form of escape—from external stressors or internal distress, pain, or trauma. We can think about such experiences, which push people to want to escape from life, as “push factors.” But I wonder: What do people believe they are escaping to, if anything? I wonder if certain beliefs about death might pull people to want to escape to death and thus act as “pull factors.”

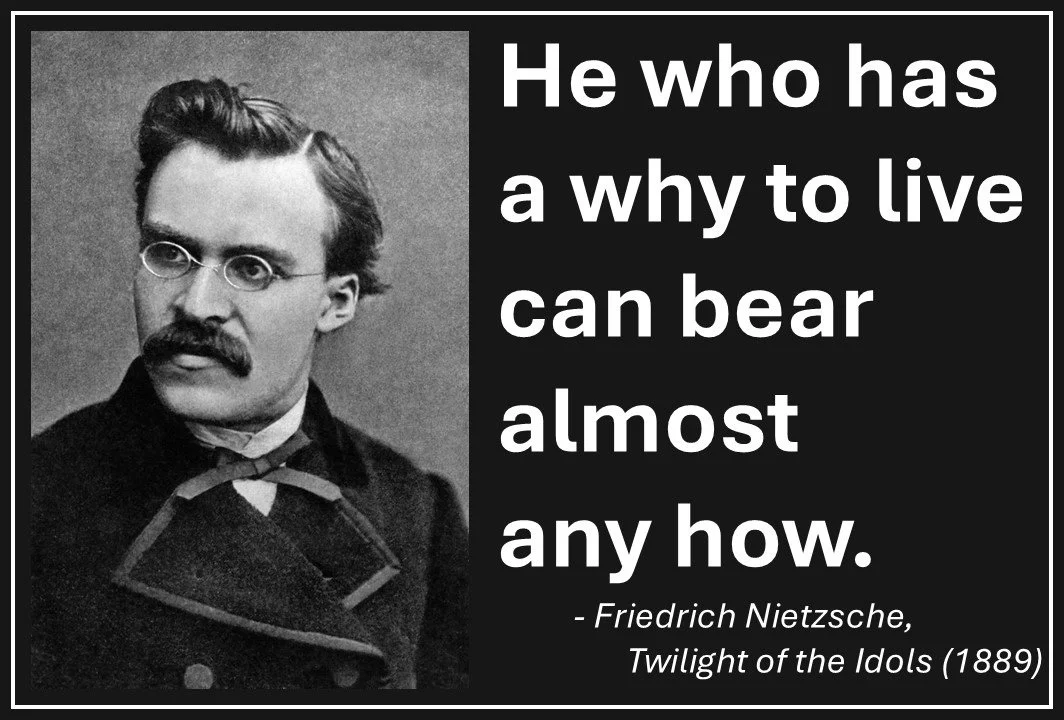

I also think meaning is critical. We often ask people to “hold on” through immense suffering. But, how do we motivate that endurance without a compelling “why”? That’s where I see existential psychology playing a protective role. As Nietzsche scrawled, in Twilight of the Idols (1889), “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

ISSEP: Fascinating! How did you develop your interests in death attitudes and suicide risk?

Grace Hart: There were at least two key experiences that helped develop my interests in death attitudes and suicide.

First, in undergrad, I started as a philosophy and psychology dual major at Randolph College, in Virginia. Initially, I wasn’t interested in research; I just wanted to do therapy. But someone I knew told me I would need to get involved in research if I wanted to go to grad school. So, I joined an embodied cognition lab under Dr. Holly Tatum. Then, after I transferred to Boston College, in my sophomore year, I worked with Dr. Katherine McAuliffe in a social development lab. Then, I started working with Dr. Courney Beard in her anxiety and depression lab. That’s where I did most of my undergraduate research. It was great—she said, look, these are the projects we’ve run and these are the data available to us, so take your pick and that will be your thesis project. I ended up picking a project on fearlessness about death and suicide. That wasn’t initially my interest, but the project really helped expose me to new ideas and new methods and I really learned a lot.

Second, while I was working on that project, I noticed that research on death anxiety and fearlessness about death seemed strangely siloed. It seemed that the topics were essentially two non-overlapping literatures and it struck me as odd that these two constructs—presumably just opposite ends of the same spectrum—weren’t being studied together. Then, I happened to be attending a conference, in 2022, where I heard Dr. Shirley Wang talk about her work toward a computational model of suicide, and she addressed exactly the challenges I’d noticed: messy measurement, fuzzy terminology, siloed literatures. That was a lightbulb moment—I realized I wasn’t imagining things; these were real issues and smart people were actively working to resolve them. I also realized all the stuff she was working on was very mathematical and computationally heavy, and that realization gave me a sort of secondary lightbulb moment as I decided I wanted to follow her lead in that area. So, I spent the rest of my undergrad building up the computational and mathematical skills I would need to contribute to that work.

ISSEP: Do you see these topics when you look at the arts and humanities?

Grace Hart: Absolutely! Once you start thinking about the role of death in life, you see it everywhere. In literature, you have the Epic of Gilgamesh—the oldest known written story. King Gilgamesh witnesses the death of his friend, Enkidu, which leads him to realize death would come for him as well. Thus, Gilgamesh embarks on a desperate and life-long journey to secure eternal life—in which he ultimately fails and is forced to accept his fate to die.

Clockwise from top left: Tablets recounting the Epic of Gilgamesh; Netflix’s 2022 comedy-horror film White Noise; the TV show Big Little Lies; Cemetry Gates (1986), by The Smiths; and Alligator Bites Never Heal (2024) by Doechii.

It shows up in all sorts of film and TV. For example, Adam Driver starred in Netflix’s 2022 comedy-horror film White Noise, which was explicitly about death anxiety. And, similarly, I think so many of us were thrilled to see Greta Gerwig’s 2023 Barbie film. It turned out to be, fundamentally, an existential film about what it means to have a body, life and death, and making your own meaning in life. Early in the film, Barbie has a record-scratch moment when she brings a party to a screeching halt by blurting out, “Do you guys ever think about dying?” But I was in the audience, thinking, “Yes! Me! I do!”

I remember reading about a similar real-life moment (Whipp, 2020), in which Nicole Kidman and Reese Witherspoon were in make-up together on the TV show Big Little Lies. Witherspoon was asking Kidman loads of questions about film lore—directors, co-stars, musical numbers, and so on—when Kidman suddenly asked Witherspoon, “Do you ever think about dying, Reese? Because I think about it all the time.” Witherspoon said she didn’t, and Kidman pressed further and learned they differed on their certainty of religious beliefs about what happens when you die. That’s powerful, and yet such conversation is often taboo in polite company.

It's also all over the place in music. For example, in Cemetry Gates (1986), by The Smiths, one of the lines is “All those people, all those lives / Where are they now? / With loves, and hates, and passions just like mine / They were born, and then they lived, and then they died.” But even when it’s not explicit, like that, it shows up in more subliminal ways and clearly motivates the content of people’s art. Even Doechii just put out an album, Alligator Bites Never Heal (2024)—which I’ve really been enjoying—which is basically all about her drive to achieve notoriety via wealth, fame, and physical attractiveness. I listen to that and can’t help but think the underlying motivation is to achieve a death-denying sense of legacy.

ISSEP: In what ways can your research help us make sense of important human experiences, better understand important events, or inform our cultural or technological trends?

Grace Hart: Most of us experience our thoughts and emotions as somewhat mysterious. We don’t always understand where they come from, and we often just rationalize a best-guess hypothesis about why we might think, feel, or behave in the ways that we do. During a crisis, it’s even more difficult to try to accurately understand yourself and design effective new ways to think, feel, or behave that will help problem solve or course correct.

That’s the advantage of having such granular EMA research data; we can use it to provide data-driven insights into our own mental patterns—especially in moments of panic or despair. Instead of requiring clients to be calm and accurate in their introspection and exercise planful coping during an impending crisis experience, predictive tools could recognize the patterns and intervene. It could be similar to the way your smartwatch or Fitbit can recognize physical health risks and help remind you to hydrate, stop snacking, or go for a walk. We might be able to develop similar predictive tools for avoiding mental health crises, which could alert you to warning signs and give you healthy interventions such as guiding you to get some exercise, keep in touch with family and friends, or reflect on your positive goals in life. Support like that wouldn’t replace therapy, of course, but it could help.

ISSEP: What do you think are some important next steps toward better understanding these experiences?

Grace Hart: I think the field needs to lay down a body of really rigorous descriptive work, using qualitative methods, before going deeper with quantitative self-reports and studies on implicit/non-conscious processes. It could be as basic as just asking people, “What do you believe happens when you die?” and “How does that make you feel?” People might know some of that material, but other parts might be a mystery to people that they just rationalize about; either way, we need a better understanding of what people do and do not experience.

Another direction that’s interesting is related to Thomas Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide, which is one of the leading theories. Part of that theory holds that in order for a person to enact a suicide attempt, one needs to acquire the mental capability to do so, and one of the ways people do that is by lowering their fear of pain and death. So, I’d like to see researchers more directly identify how people who are on the path toward a suicide attempt ultimately change how they engage the topic of death and the ways they think about it.

To try to help contribute to that effort, I’ve been experimenting with natural language processing (NLP) of people’s descriptions of the way they think about death. For example, I identified a big Reddit thread where the opening question was “What do you think happens when you die?”, and scraped all the comments, fed them into a readable file, and used an NLP topic modeling technique to try to categorize the response content. It’s still early days, but I hope this hybrid of qualitative richness and quantitative computational efficiency will help us better understand how people think and feel about death.

ISSEP: What is some advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Grace Hart: I’ve got a few pieces of advice. First, read widely and deeply. Second, plug in and pay attention. Join ISSEP, pay attention to the monthly newsletter, check out these Features and Spotlights articles, follow their social media postings, things like that. It's a great resource to get familiar with some of the major players in this research area. When I was an undergrad, and I was first becoming interested in existential psychology, it was so helpful to have ISSEP as the flagship society where people were organizing.

Third, talk to people. If you’re excited about some research, you can literally just cold-email the researchers to tell them you found it interesting and would like to chat about collaborations, or future directions, or whatever—you’d be surprised how many would be willing and excited to chat with you. Conferences are also a great place to connect and talk with people that way. Fourth, trust your instincts. If something feels off in the literature or in practice, don’t just assume you’re misinterpreting things because you’re early in your career. That might be the case, but also some of your best and most productive gains can come from questioning things that don’t make sense.

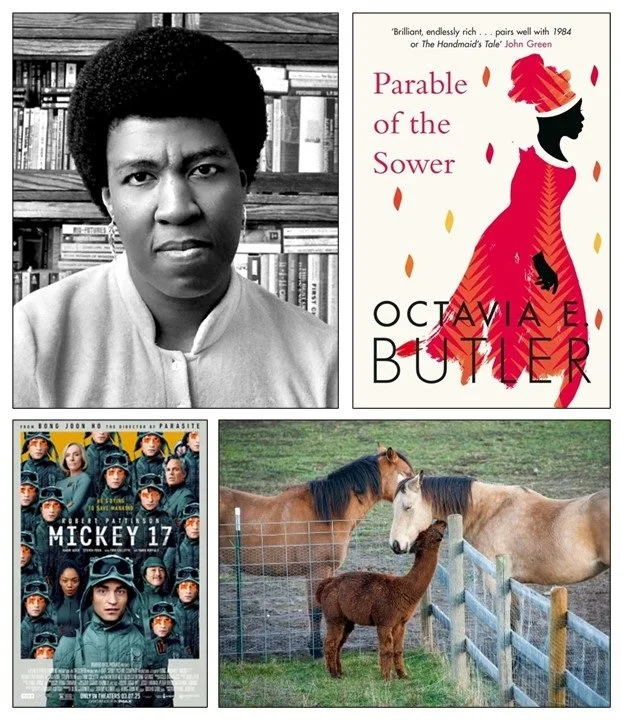

Clockwise from top left: Octavia Butler and her book Parable of the Sower (1993), hobby farm with horses and alpaca, and Mickey 17 (2025).

And fifth and finally, it’s never too late to shift directions. So, if you’ve traveled partway down a path and you discover a better and more productive path to travel, it’s okay to change directions. I didn’t get into computational modeling until my junior year, and it’s now central to my work. If something excites you, follow it. Let passion lead, even if the path isn’t linear.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the work/research context?

Grace Hart: I grew up in rural Spotsylvania County, Virginia on a hobby farm with alpacas, horses, a mule, and some chickens. So, I grew up with a bit of American country girl lifestyle, riding horses, and I enjoy reconnecting with nature when I go home. Since college, I’ve also taken up yoga, I enjoy cooking, and spending time with friends. I also really enjoy reading, checking out films, and going to music concerts. I read everything from philosophy to romance novels.

My favorite book of all time is Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia Butler. The protagonist is, in many ways, such a quintessential existential hero. She really seizes her radical freedom amid absolute chaos; she’s just so sure of her vision. I find it an incredibly inspiring and powerful narrative.

In terms of film, I recently saw Mickey 17 (2025) and loved it—another excellent existential film that raises deep questions about the mind-body problem, identity and the teletransportation paradox, and mortality.

And in terms of concerts, I recently saw Tyler Childers live, which was incredible. I just adore his music. His song Born Again (2017) is one of my favorites.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music while working or otherwise, what are you listening to lately?

Grace Hart: I’ve definitely been listening to Doechii’s latest album, Alligator Bites Never Heal (2024), including Anxiety in particular. It’s phenomenal. She does such a great job bringing in innovation and her own unique twist on things, while also paying homage to the tradition of the genre. For example, Denial is a River makes me think about Eazy-E and Slick Rick and some of the other early rap artists in a way that I’m sure was intentional. Her music is really exciting.

I also love some of the small Americana music artists from southwest Virginia, like Dori Freeman, Viv & Riley, and Alexa Rose. My tastes are broad, but I keep coming back to those artists.