Neil Wegenschimmel on Meaning, Misinformation, and Uncertainty

Neil Wegenschimmel is a Ph.D. student in social psychology at the University of Waterloo, with MA’s in both psychology and sociology. He is broadly interested in cultural and social change, political psychology, personality, meaning and belief in different contexts (religion, extremism, polarization, and nihilism), media and information consumption, and the effect of digital social life on what we see as being real or true. He is currently researching how differences in metacognition might influence authoritarian beliefs. Outside of psychology, Neil reads and writes widely while maintaining a life-long love of music-making, vinyl records, literature, travel, and history.

Neil on the web: Lab Website | Google Scholar

By Nicholas Kelley, University of Southampton. August 15, 2025

ISSEP: How did you first become interested in existential psychology?

Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Viktor Frankl, and Erich Fromm have each explored the existential challenges of navigating informational uncertainty to create a sense of meaning in life.

Neil Wegenschimmel: My path shares some familiar starting points with others in this area, but it also took a few unexpected turns that shaped how I think about existential questions. As a teenager, I started reading writers like Nietzsche, Camus, and Sartre, even if I didn’t fully understand them at the time. Still, their ideas stayed with me. Over time, I found myself diving deeper into thinkers like Viktor Frankl and Erich Fromm and that’s when things started to click for me in a more psychological sense.

I’ve also always been interested in art that explores existential themes—films, music, literature that wrestle with meaning and identity. And I’ve had a long-standing curiosity about religion, history, and cults. Not in a sensational way, but in terms of how they work psychologically. I was especially drawn to the utopian cults of the 1960s and 70s, or groups that eventually evolved into self-help movements. I find it compelling how people’s search for meaning can lead them to intense, sometimes radical commitments. When I look back, it’s clear how those early interests connect to the research I’m doing today.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research in existential psychology lately. Can you tell us more about your work?

Neil Wegenschimmel: The project I presented at the SPSP Existential Psychology Preconference focused on how people respond when the world starts to feel unstable or untrustworthy, especially in political and informational contexts. The main idea behind the project was to understand how people respond to a feeling that the world is no longer trustworthy or stable, especially when it comes to political and informational environments. We introduced a novel framework by examining how two distinct metacognitive orientations: conspiracy mentality, the belief that powerful groups are hiding the truth, and existential nihilism, the belief that life lacks inherent meaning differentially relate to authoritarian attitudes on the political left and right.

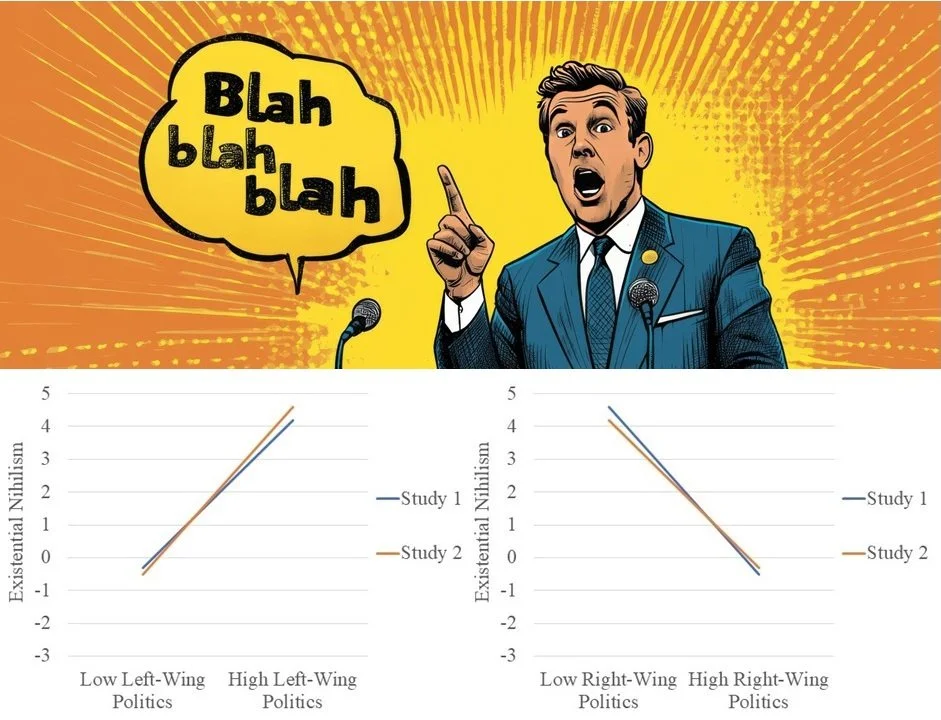

In both Studies 1 and 2, existential nihilism was positively associated with left-wing political orientation and negative associated with right-wing political orientation.

In Study 1 (N = 386 American adults), we found distinct associations between these orientations and authoritarian attitudes. Conspiracy mentality predicted both right-wing (β = 0.10) and left-wing (β = 0.11) authoritarianism, while existential nihilism negatively predicted right-wing authoritarianism (β = -0.14) and positively predicted left-wing authoritarianism (β = 0.24). This suggests these orientations are not simply downstream of political ideology—they may guide how people process instability.

In Study 2 (N = 502 American adults), we asked whether people’s perceptions of growing societal extremism could be shifted by providing accurate historical context. Half of the participants were randomly assigned to view data on past political violence in the U.S and half were given no such information. Surprisingly, there was no significant difference between groups. Even when shown that past eras were also extreme, people’s belief that society had become more radical remained unchanged. This suggests that these perceptions may be resistant to factual correction.

We also replicated our earlier findings Conspiracy mentality again predicted right-wing (β = 0.33) and left-wing (β = 0.07) authoritarianism. Likewise, existential nihilism again negatively predicted right-wing authoritarianism (β = -0.11) and positively predicted left-wing authoritarianism (β = 0.30). Additionally, both left-wing authoritarianism (β = 0.18) and Conspiracy mentality (β = 0.21) predicted the belief that society had become more extreme.

In Study 3, we tested a dual-path model that links upstream emotional states (like loneliness and uncertainty) to downstream authoritarian beliefs. Uncertainty indirectly predicted right-wing authoritarianism via conspiracy mentality (β = 0.04) and left-wing authoritarianism via existential nihilism (β = 0.06). Loneliness only indirectly predicted left-wing authoritarianism via existential nihilism (β = 0.07). Information consumption also had indirect effects on right-wing authoritarianism (β = 0.07) and left-wing authoritarianism (β = 0.08), with large total effects on both (right-wing authoritarianism: β = 0.47; left-wing authoritarianism: β = 0.41). These findings suggest that common emotional drivers like uncertainty and loneliness can set the stage for conspiracy mentality and existential nihilism, which then diverge toward different ideological expressions.

People are trying to make sense in an uncertain, unstable world.

What's interesting is that we’ve replicated these findings across culturally distinct samples in both the UK and Canada, and the relationships are holding up. So there really seems to be something there. The idea is that people are trying to make sense of an unstable world, and these different tendencies shape how they respond, either by withdrawing or by adopting more rigid ideological commitments.

ISSEP: Fascinating! How did you develop your interests in this topic area?

Neil Wegenschimmel: I think it started during adolescence. When I entered middle school, I had this experience where the world suddenly felt unfamiliar. The meaning systems that made sense in childhood no longer seemed to apply. That shift brought on a kind of discomfort I didn’t know how to name at the time. I remember asking myself questions like, “What’s wrong with me?” or “What am I supposed to be doing with my life?” At that age, it’s hard to talk about those things, so you end up feeling pretty isolated. Those early experiences got me thinking more seriously about meaning, identity, and purpose. Over time, that curiosity became more focused and eventually shaped my academic path. I also started noticing how those same kinds of existential questions surface in cultural and political life, especially online. That link between personal confusion and collective behavior is really what drew me into this research.

ISSEP: In what ways can your research help us make sense of important human experiences, better understand important events, or inform our cultural or technological trends?

Neil Wegenschimmel: Well, I see a lot of the existential themes that I study showing up in music. There’s often a tension between disorientation, detachment from the world, and a longing for meaning. That’s probably what draws me to it, and the themes in the music often mirror the kinds of questions I explore in my work.

In response to uncertainty and instability, some react by becoming rigid and dogmatic while others disengage or lose any sense that truth matters. Clockwise from upper left: Many people become overinflated with confidence; Marcel Duchamp rejected art as meaningless waste in his Dadaist sculpture of a signed porcelain urinal, The Fountain (1917); many people similarly reject politics as meaningless waste.

Also, one of the main insights from my research is that people’s metacognitive tendencies shape how they respond to uncertainty and instability. Some react by becoming rigid and dogmatic, while others disengage or lose any sense that truth matters. Both responses can be dangerous, especially when it comes to politics. You can see these dynamics playing out in events like the Canadian election. There was a lot of misinformation and distrust, but we didn’t see a full collapse into authoritarianism or widespread nihilism. That might reflect something about Canada’s political culture or institutional norms. It could also be that people there have more trust in democratic processes, or less exposure to the kinds of media ecosystems that amplify extreme reactions. What this highlights is that it’s not just about what people believe, but how they come to hold those beliefs. If someone approaches the world through a lens of suspicion or despair, they will interpret new information very differently. That has real consequences for how we communicate across divides. It suggests that simply offering more facts won’t be enough. We also need to think seriously about how platforms, educators, and institutions shape the very ways people engage with knowledge in the first place.

ISSEP: What do you think are some of the remaining issues in this research, and what do you see as the most important next steps for understanding these experiences?

Neil Wegenschimmel: One major challenge is figuring out how and why people come to rely on different metacognitive orientations when facing uncertainty. We know that conspiracy thinking, and existential nihilism are both linked to authoritarianism and political disaffection, but we don’t fully understand why some people lean in one direction while others respond differently. That’s an open question I think future work really needs to address. Another issue is how to study these responses in more dynamic environments. Much of the current research depends on fixed survey items, but people’s sense of meaning or trust can shift rapidly depending on context, social cues, or the media they’re consuming. We need better tools for capturing those real-time shifts as they unfold. I also think we need to take seriously the influence of new technologies on how people navigate knowledge and belief. AI-generated content, personalized algorithms, and deepfakes are not just shaping what people believe. They’re changing how people relate to the very concept of truth. That shift has serious implications—not only for political and media systems, but for how individuals make sense of their lives and connect with others.

ISSEP: You’ve attended and presented research at our Existential Psychology Pre-conferences; how has your experience been with those?

Neil Wegenschimmel: This was my first time attending the Existential Preconference in person. I’d seen some of the talks online before, but being there in the room made a big difference. The atmosphere was incredibly welcoming, and the conversations were thoughtful and energizing. Honestly, I preferred it to the main conference. It felt more focused, more intellectually engaged, and more aligned with the kinds of questions that brought me into this field in the first place.

I also really valued the opportunity to share my work with people who truly understand the nuances of existential theory and research. There was a shared sense of curiosity and openness that made the whole experience feel both rigorous and collaborative. It was a great experience overall, and I’m already looking forward to the next one.

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Neil Wegenschimmel: If I had to give one piece of advice, it would be to read as widely as you can. Don’t just stick to psychology. Literature, history, philosophy, and art are filled with important material that can deeply shape how you think. Some of the most important insights in my work have come from ideas I first encountered outside of psychology.

Also, talk to people, especially those whose work excites you. Academic communities thrive on shared curiosity, and in my experience, most scholars are more than happy to connect if you reach out. And don’t be afraid to say things out loud that you haven’t fully figured out yet. Some of the best thinking happens in conversation, not just in isolation. You can’t stay buried in books forever. At some point, you have to test your ideas by engaging with others. But for me, reading widely is what opened the door in the first place and it’s still what keeps me intellectually grounded.

“Read as widely as you can. Don’t just stick to psychology. Literature, history, philosophy, and art are filled with important material that can deeply shape how you think.”

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the work/research context?

Neil Wegenschimmel: Before I returned to school, I worked as a musician for a while—doing commercial work, composing for short films, and playing in a few bands. Piano was my first instrument, but I mostly played guitar and picked up some drums along the way. The pandemic hit that part of my life pretty hard, but I still try to make space for it when I can. I still try to stay connected to music, even if it plays a smaller role in my life now.

I also spend a lot of time walking. It’s one of the few things that helps me think clearly and step away from screens and structure for a while. Reading is another constant—especially philosophy, cultural criticism, and history. Even when I’m not reading with a research question in mind, I find those ideas often end up shaping how I understand people and society. I try to keep my interests broad. It helps me stay curious and engaged, and it gives me more ways to connect ideas that might not seem related at first. That kind of cross-pollination has been really important to how I approach both life and research.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music while working, what are you listening to lately?

Neil Wegenschimmel: I tend to gravitate toward British post-punk and darker, moodier music. Some of my favorites are Joy Division, Wire, The Jesus and Mary Chain, Echo and the Bunnymen, and Killing Joke. I’m also a big David Bowie fan.

Lately, I’ve been kind of addicted to an album called Nothing by a group called Darkside. It’s a project from the composer Nicolas Jaar, and it blends dub, electronic music, jazz, and funk in a way that feels really distinctive. It’s one of those albums that doesn’t sound like anything else—a really compelling mix of electronic, dub, and jazz; atmospheric without being distracting. It’s great for writing; I was actually listening to it on my walk into the lab this morning.