Michael Mask on nostalgia, meaning, and mystical experiences

Michael B. Mask is a graduate student in Psychology at the University of British Columbia. His research is based in cross-cultural existential psychology and has explored how people around the world derive meaning and purpose. He is also interested in how people navigate meaning-making in the wake of trauma, with a focus on nostalgia, mystical experiences, and the emerging “spiritual but not religious” movement. He is the recipient of several awards, including the UBC Faculty of Arts Graduate Award, the Canada Graduate Scholarship (Master’s), the Cross-Cultural Existential Psychology Research Award, and the Worth Publishers Student Conference Award.

Michael on the web: ResearchGate | Twitter | YouTube

By Nicholas Kelley, University of Southampton. July 28, 2025

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and the science of existential psychology?

Michael Mask: About seven years ago, my entire life fell apart. I was struggling with drug abuse, mental health issues, and financial instability. I was living in my parents basement and was in a pretty dark place; I sort of felt as though my two options were either suicide or a major life transformation.

Clockwise from top left: Warsaw Royal castle and old town at sunset; Taumadhi Square, Bhaktapur, Nepal; people meditating in a retreat.

So, I started desperately seeking a way out, and that led me to spirituality and the big existential questions. I did some traveling in Poland, got really into Taoism, Zen Buddhism, and Advaita Vedanta, and spent two years in India and Nepal. I stayed in an ashram in India for six months and completed a couple of ten-day silent Vipassana retreats. In those spaces, I met a lot of people who were recovering from trauma or searching for something deeper. My personal experiences, along with those conversations, inspired my interest in mystical experiences and post-traumatic growth.

I also started watching people like Gabor Maté and Jordan Peterson. I know Peterson’s controversial, and I don’t agree with everything he says, but the message of finding meaning through personal responsibility struck a chord. The idea of beginning to transform your life at the granular level was really important—sometimes it seemed so simple as to be absurd, like just cleaning up your room, but it turned out to be really transformative. That mindset helped me stop blaming everyone and start taking ownership over my life choices.

Then, in my fourth year of undergrad, I took a course on existential psychology, taught by Steve Heine. I remember doing projects on important experiences like nostalgic memories and meaning in life, and that really pulled me into the field. So, my journey started in my parents’ basement, involved traveling around the world, and eventually led to doing a Master’s and PhD in existential psychology.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research in existential psychology lately. Can you tell us more about your work?

Nostalgic images of a road trip and various vintage technologies such as cassette tapes, VHS tapes, tube televisions, film cameras, and typewriters.

Michael Mask: Sure! So far, I’ve conducted studies with my advisor, Steve Heine, on three main topics: nostalgia, meaning in life, and mystical experiences.

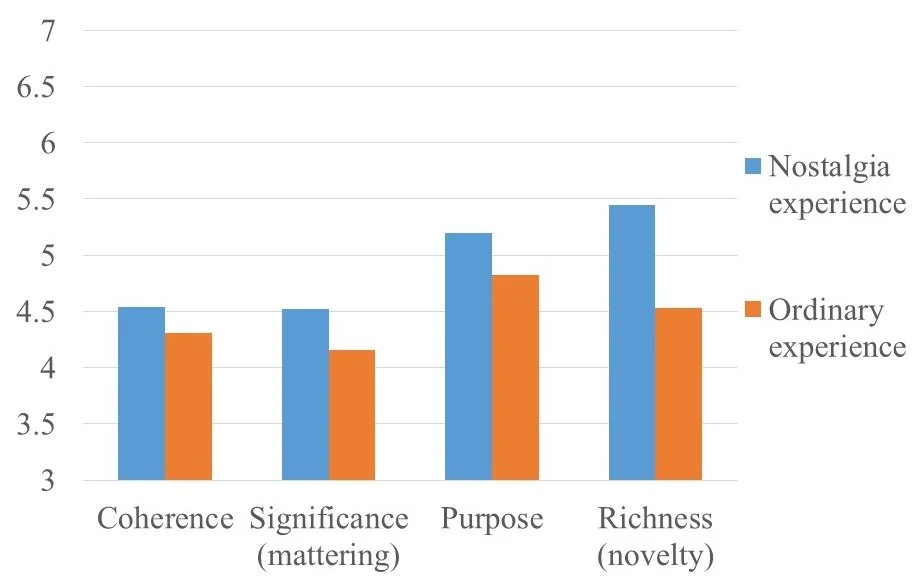

In our nostalgia work, we looked at how reflecting on nostalgic memories affects meaning. Prior research has found that nostalgia boosts meaning in life (Wildschut & Sedikides, 2025), and our research expanded that work by exploring whether nostalgia impacts all three core facets of meaning: coherence, purpose, and significance/mattering. Given that nostalgia entails a “sentimental longing for the past,” there was good reason to hypothesize that nostalgic reflection would be associated with all three components. Because nostalgic reflection involves seeing continuity between the self and others from the past to the present, it should increase a sense that the world involves coherent connections between people and events over time. By the same token, it may serve as a reminder of a time in which we felt loved by important others, and have since set out on our life’s journey, which could promote a sense of significance and purpose.

To test these ideas, we first manipulated nostalgia using the Event Reflection Task Sedikides et al., 2015). In the nostalgia condition, participants were first presented with a description of nostalgia and instructed to bring to mind a nostalgic event in their lives, reflect on the event, and consider how it made them feel. In the control condition, participants were presented with a description of an ordinary event and instructed to recall a routine or emotionally neutral past experience. In both conditions, participants summarized the event with four keywords and wrote about it for up to five minutes. Then, we measured the three components of meaning in life: coherence (e.g., I can make sense of the things that happen in my life), purpose (e.g., I have aims in my life that are worth striving for), and mattering (e.g., even considering how big the universe is, I can say that my life matters) using George and Park’s (2017) Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale.

Data from Mask’s studies, finding that reflecting on a nostalgic event (vs. an ordinary event) led to greater perceived meaning in life (coherence, purpose, and significance), as well as a greater sense of psychological richness.

The data patterns showed that nostalgic reflection led to an increase in each of the three components of meaning in life. We then did follow-up research and found that nostalgic reflection also enhances the sense of psychological richness; nostalgia leads people to feel more strongly that their lives are filled with diverse, perspective-changing experiences, and these effects hold even when controlling for factors like happiness or demographics.

The project I presented at the Existential Psychology SPSP Preconference involved a cross-cultural study with Steve Heine looking at sources of purpose in life across the US, Poland, Japan, and India (Mask, Dunigan, & Heine, 2025). Going in, we really expected to see major cultural differences in what gives people a sense of purpose. We thought that sources of meaning would vary widely — say, that individualistic societies might emphasize personal goals, while collectivist ones might focus more on community or family. But what surprised us — and honestly moved us — was how much overlap there was. Across the U.S., Poland, Japan, and India, people consistently highlighted family, happiness, and self-sufficiency as key drivers of purpose. These weren't just popular in one place — they showed up everywhere. It was a beautiful reminder of how shared our human experiences can be.

Lastly, I’ve recently been drawn to questions around mystical experiences, particularly in people whose sense of meaning has been disrupted by things like trauma or addiction. I’m curious about how these profound, self-transcendent experiences might help people rebuild a connection to life, others, and even spirituality. That’s a major direction I hope to explore further.

ISSEP: Do you see existential psychology topics when you look at the arts and humanities?

Counter-clockwise from top left: Cheryl Stayed, her 2012 memoir Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail, and the Reese Witherspoon film based on her story.

Michael Mask: Absolutely. I remember back in my undergraduate Existential Psychology course—fresh off my own experiences with addiction, confrontation with mortality, and self-transformation journey—we viewed the film Wild with Reese Witherspoon. It’s about a woman, Cheryl Strayed, who has a good life, a loving partner, and a close relationship with her mother. But then she must watch helplessly as her mom suffers from cancer, rapidly declines, and then passes away. As a result, Cheryl copes in maladaptive ways, destroying her relationship with her partner and spiraling into a heroin addiction. Eventually, she hits bottom, and decides to leave everything behind to solo hike the Pacific Crest Trail in an attempt to transcend her situation and transform herself. Ultimately, through her experiences on the trail, she succeeded in growing from her traumas and developing a new sense of meaning in life.

Strayed’s journey reflects a maladaptive response to existential threat, seeking escape through drugs, but then a journey to personal growth and seeking healing through nature, solitude, and challenge. Along the way, it really highlights the complicated nature of one’s life narrative. Nostalgic connection to the past can be a source of meaning. But also, life’s obstacles can really hinder us in both mind and body. Yet, a meaningful redemption narrative, in the style of a hero’s journey, can help to restore a sense of meaningful coherence, significance, and purpose.

A similar thematic progression can be seen in the Buddha’s hagiography—trauma, shattered meaning frameworks, spiritual journeys, post-traumatic growth, and transcendent experiences. After a comfortable princely life, Siddhartha Gautama (Buddha) has a series of traumatic experiences as he encounters, for the first time, extreme suffering in the world, including old age, sickness, and death. His sense of meaning is shattered as he is unable to integrate these experiences into his sheltered worldview. So, he abandons his family, his inheritance, and his palace, and he embarks on a spiritual journey to make sense of life given suffering and death. He has a series of profound spiritual experiences, culminating in his enlightenment while meditating under the Bodhi Tree in Northern India. He then spent the remainder of his life sharing his new views on the path to meaningful spiritual enlightenment.

The two stories show some cultural differences, of course, but they are also remarkable for their similarities—perhaps suggesting a cross-culturally universal set of sources of meaning and possibly even meaningful spiritual journeys.

ISSEP: What do you think are some of the remaining issues or important next steps toward better understanding these experiences?

Michael Mask: When it comes to mystical experience and spirituality, especially within the “spiritual but not religious” space, it’s kind of the wild west right now. There’s a lot we don’t understand. Many people are identifying as “spiritual but not religious.” That shift matters because religion has long provided a framework for meaning, values, and community. If people are leaving those frameworks behind, we need to understand what’s leading them away from it and what’s filling the gap. Mystical spiritual experiences might provide a sense of connection, unity, or awe, things people are craving. And in cases where people are reeling from trauma, such experiences might not only help people heal but might also reorient them toward new sources of meaning. So, I think cross-cultural existential psychology research on that topic could matter not just for mental health, but also for understanding broader social and cultural changes in the way people find meaning without religious institutions to guide them.

“Be open to getting outside your comfort zone and exploring new experiences... it’s a good habit for anyone interested in studying existential psychology.”

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Michael Mask: I think the best advice would be to both believe in your goal and work hard to accomplish it. And you can take my experience as an encouraging example: If someone like me can do it, you can too. Just take responsibility and work hard, and stick to it and don’t give up.

Also, be open to getting outside your comfort zone and exploring new experiences. Maybe you’re familiar with urban life, and you have the opportunity to go to a rodeo in a rural town? Go, check it out and try to understand the experience. Someone recently invited me to Divine Liturgy (similar to Catholic Mass) at an Orthodox Church, during a psychology conference. It was unfamiliar territory for me. But I went and it was really a new and fascinating experience, which led me to see a lot of cross-cultural parallels with some of the more ancient Eastern and Indic religions. That openness to experience has helped shape my thinking and it’s a good habit for anyone interested in studying existential psychology.

Clockwise from top left: Lillian Lake trailhead, Galatea Creek suspension bridge, and Lillian Lake.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the work/research context?

Michael Mask: Hiking is a major source of meaning and perspective for me. I’ve done some good treks in Nepal. One of my favorite trails in Canada is the Lillian Lake route in Kananaskis Country, Alberta. It starts in a quiet forested valley, follows creeks and wooden bridges, and eventually opens up to breathtaking alpine views as you climb the mountains. That kind of immersion in nature helps me recharge, reflect, and reconnect.

I also sing and play the guitar. I played guitar in a band, back in high school, and when I was traveling I started to publicly sing as well. Mostly blues, progressive rock, psychedelic rock, that sort of thing.

Sauna sessions and swimming at the local aquatic center are also part of my routine when I want to unwind. But through it all, nature and music continue to ground and inspire me.

ISSEP: You’ve attended and presented research at our Existential Psychology Preconferences; how has your experience been with those?

Michael Mask: I’ve attended the preconference two years in a row, but this past year was my first time attending in person. It was energizing and inspiring. One highlight was giving a flash talk about my cross-cultural meaning and purpose research. It was a fun and incredibly rewarding experience! I enjoyed the challenge of distilling key insights into a short format, and it was reassuring to see it resonate with the audience.

The main talks were packed with passionate, engaged people. I really enjoyed Daryl Van Tongeren’s presentation about the religious “dones”—the content was really eye-opening and the presentation was humorous and charismatic. It really made me feel energized to do work on that topic, too! My other favorite part was the social time afterward, especially getting to talk with folks at the cocktail party.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music while working, what are you listening to lately?

Michael Mask: If I’m working on a manuscript, or something like that, then I can’t really listen to music much because it distracts me from my own thoughts. But I do like to listen to music most other times—including when I’m doing stats, analyzing data with R. There’s something about that where the music actually helps energize me and puts me in a good mindset to focus.

Lately, I’ve been listening to a lot of Creedence Clearwater Revival. Their Greatest Hits album have been the soundtrack to a lot of my late-night data analysis. Some of my favorite songs are Have You Ever Seen the Rain? and Midnight Special.