Jon Sundby on aging, death anxiety, and ego integrity

Jon Sundby is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs. He earned his B.A. in political science and policy studies from Grinnell College. His research explores how existential concerns intersect with aging and adult development, particularly how existential and philosophical orientations shape physical and social well-being. His work has also examined how political ideologies influence attitudes toward homelessness and how aging affects engagement with thoughts of death. Clinically, Jon provides psychotherapy to older adults and caregivers in the Colorado Springs community. He is committed to deepening the understanding of existential issues across both academic and clinical settings.

Jon on the web: ResearchGate | LinkedIn | GoogleScholar

By Muireann O’Dea, University of Kaiserslautern-Landau. August 12, 2025

ISSEP: How did you first become aware of and interested in existentialism and the science of existential psychology?

Jon Sundby: My interest in existentialism began during my undergraduate studies, where I took a number of philosophy courses. At the time, I was planning to pursue a career in law, but after spending some time in that world post-graduation, I realized it wasn’t the right path for me. I began exploring psychology and came across a clinical psychology master’s program at the University of Colorado Colorado Springs (UCCS).

While researching the faculty, I discovered the work of Dr. Tom Pyszczynski, whose research immediately caught my attention. I reached out to him, and we ended up exchanging a series of in-depth emails. I was drawn not only to the breadth of his research but also to his intellectual curiosity and openness to engage with diverse topics. His work resonated deeply with the existential philosophy I had been exposed to during my undergraduate years. Eventually, I joined his lab, which became my entry point into the world of existential psychology. Dr. Pyszczynski has since retired—I was part of his last cohort of students—but I’ve continued my research under the mentorship of his colleague, Dr. Leilani Feliciano. Although her background is more rooted in health psychology, she’s been incredibly supportive of my continued focus on existential questions. For me, existential psychology is compelling because it brings meaning and depth to understanding the human experience. Listening to people’s life stories and recognizing the patterns that emerge has become a powerful source of inspiration, offering insight into how we make sense of ourselves and the world around us.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research in existential psychology lately. Can you tell us more about your work?

Jon Sundby: Thank you! My research interests within existential psychology have been quite broad, thanks in part to my time in Dr. Tom Pyszczynski’s lab, where I was involved in several diverse projects. The work that has resonated most deeply with me, and formed the basis of my master’s thesis, looked at aging and terror management defenses.

I’m currently in a geropsychology doctoral program, which focuses on the psychological health of older adults. Drawing on previous research by Dr. Molly Maxfield, we explored how older adults respond differently to death reminders compared to younger adults. Her work—and broader literature in aging—suggests that older adults often respond with greater generativity and more positive psychological coping mechanisms. I was particularly interested in why this difference exists.

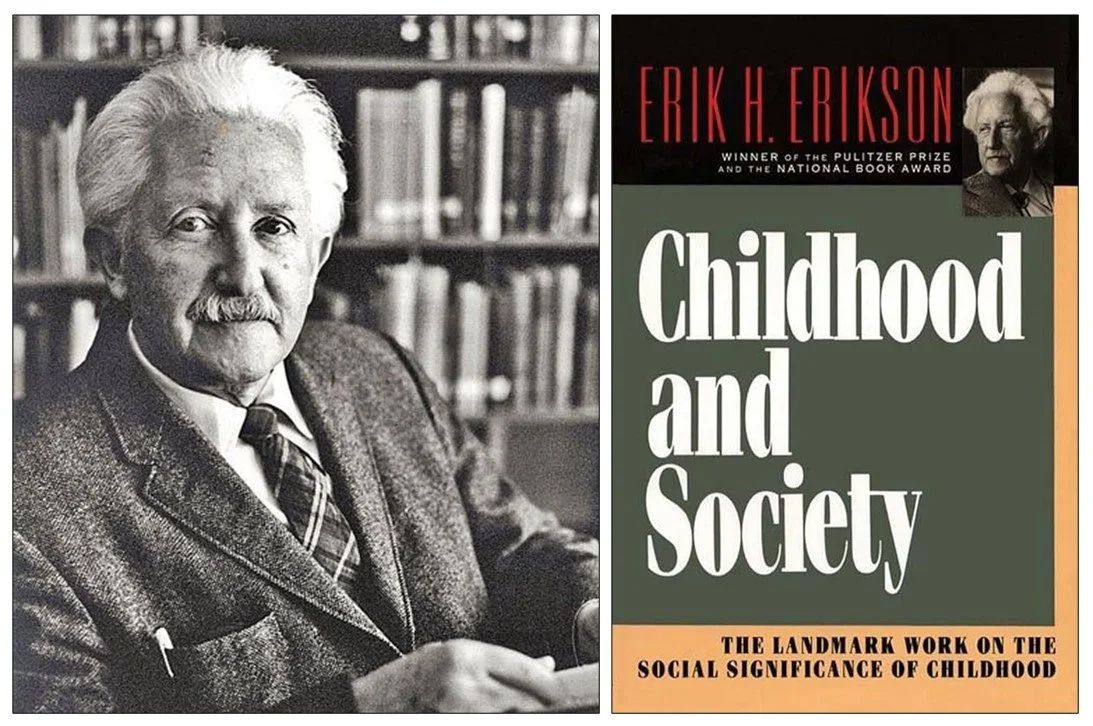

Erik Erikson and his book Childhood and Society (1950), in which he presented the idea that healthy development leads to the integration of the self into a meaningfully coherent understanding of the world. The opposite of ego integrity, in his view, is “signified by fear of death: the one and only life cycle is not accepted as the ultimate of life. Despair expresses the feeling that the time is now too short...to try out alternative roads to integrity.”

To explore that, we focused on Erik Erikson’s concept of ego integrity—the idea of achieving a sense of coherence and acceptance around one’s life story. Our research replicated existing findings that higher ego integrity is associated with lower death anxiety and greater generativity. However, when testing for terror management defenses using a standard death-priming method, our manipulation didn’t produce significant results—perhaps due to the limitations of conducting this type of study online. I hope to revisit this in an in-person setting or with different methods in the future.

In parallel, I’ve been conducting research on the intersection of existential meaning and homelessness in the United States, in collaboration with Dr. Joey Wagner. This line of inquiry grew out of my own experiences volunteering in Denver, a city facing a significant housing crisis. Our studies have explored how people’s political ideologies shape their perceptions of homelessness and support for related policies. One project tested whether framing homelessness as a veterans' issue—a group often held in high regard, especially by politically conservative individuals—would increase public support for housing initiatives. While support did increase across the board when the issue was framed around veterans, deeper ideological predictors such as right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation remained strong barriers to support.

Another study we’re working on looks at broader ideological frameworks—like belief in the Protestant work ethic and neoliberal meritocracy—and how they predict opposition to supportive housing policies. We found that individuals who strongly endorse these beliefs were more likely to support punitive rather than supportive responses to homelessness. These findings underscore how existential and cultural narratives influence both policy attitudes and our collective moral reasoning.

Both threads of my research—on aging and homelessness—share a core focus: understanding how people create meaning in the face of existential challenges. Whether it's through the lens of ego integrity in later life or the narratives people construct to make sense of social inequality, I’m fascinated by how our internal worlds interact with societal structures and shape our psychological well-being.

ISSEP: Fascinating! How did you develop your interests in that topic area?

Jon Sundby: My interests in existential psychology—and particularly in topics like aging and terror management—have developed through a combination of academic training and real-world experience. I studied politics and philosophy which gave me a broad and interdisciplinary foundation. That background sharpened my interest in the larger environmental, social, and political forces that shape psychological issues. Even now, those themes continue to inform how I think about psychological research.

As I moved into psychology, I became increasingly drawn to questions about how people find meaning in the face of challenges—especially as they age. Working with mentors like Dr. Tom Pyszczynski and Dr. Joey Wagner and through volunteer work, I began thinking about how existential concerns manifest in different populations, including older adults and people experiencing homelessness. Chronic illness, health anxiety, and physical decline are common experiences in later life, and they significantly impact one’s sense of meaning and well-being. I’m curious about how we can better understand the resilience many older adults exhibit, and whether the psychological strengths we often see in later life—such as ego integrity or a coherent life narrative—can be cultivated earlier in the lifespan.

ISSEP: In what ways can your research help us make sense of important human experiences, better understand important events, or inform our cultural or technological trends?

Jon Sundby: A central goal of my research is to better understand how people navigate existential challenges—especially in the context of aging, health, and social adversity. For instance, my work on ego integrity and death anxiety in older adults sheds light on why many people actually experience greater psychological well-being later in life. It challenges the common assumption that aging is primarily a period of decline, and instead highlights how older adults often develop a deeper sense of meaning, coherence, and perspective. By exploring why these existential strengths tend to emerge with age, we can begin to ask how we might foster them earlier in life—through interventions, community support, or even cultural messaging. I think that has wide implications, especially as societies grapple with issues like loneliness, rising anxiety, and the psychological effects of disconnection in the digital age.

In the same vein, I’m really fascinated by how different cultures support healthy aging. For instance, the Blue Zones—regions where people live significantly longer and healthier lives—offer some powerful insights. What stands out to me most isn’t just the diet or exercise routines, but the strong social component. In these communities, individuals are deeply connected to one another across generations. This is consistent with a strong body of evidence that suggests strong interpersonal relationships are critical to aging well. At the same time, we’re living through what some have called a crisis of connection, with increasing rates of isolation and loneliness. I think if you're missing this social element, then you're missing a massive part of not only what makes us healthy, but what makes us human.

Similarly, my research on homelessness and ideology looks at how cultural narratives and political beliefs shape our responses to vulnerable populations. Understanding these dynamics can inform not just policy, but also public discourse—how we talk about responsibility, support, and what it means to live a meaningful life under difficult conditions. Ultimately, I hope my work contributes to a broader conversation about what it means to live well—both individually and collectively—in the face of uncertainty, adversity, and change,

ISSEP: Do you see existential psychology topics when you look at the arts and humanities?

Jon Sundby: Absolutely. One of the first things that comes to mind is the way Western culture often shows an aversion to aging. In much of mainstream art and media, there's a strong emphasis on youth, vitality, and glamour. Aging, by contrast, is something we tend to avoid or downplay. That cultural denial makes open reflections on aging and mortality somewhat rare in popular media. That said, I do think we’re beginning to see more thoughtful representations of aging and existential themes, particularly in the work of older artists. There’s a growing number of films, books, and creative works that offer meditative explorations of aging, death, and what it means to live a meaningful life. These themes often appear subtly, woven into more reflective or personal pieces rather than overtly commercial ones.

Bottom/right: Ernest Becker and his book The Denial of Death (1973),. Upper/left: Iris Murdoch and her book The Sea, the Sea (1978).

The Denial of Death (1973), by Ernest Becker, comes to mind quickly—it’s had a lasting impact on how we think about these topics culturally and psychologically. I also read this book recently called The Sea, the Sea (1978), by Iris Murdoch. It’s about this old British playwright who moves to the sea, but it's kind of like a meditation on death. He tries to deny it by igniting a romance with an old flame who's actually not into him, but he's obsessed with the idea of her, as a terror management strategy of sorts. I'm sure there are other powerful examples in literature and the arts, and it's something I’d like to reflect on more deeply. It’s a great question—and a reminder of how deeply interconnected psychology and culture really are.

ISSEP: What do you think are some of the remaining issues or important next steps toward better understanding these experiences?

Jon Sundby: One of the most important next steps, in my view, is expanding the use of qualitative research to complement existing quantitative approaches. We’ve gathered a lot of valuable data on variables like meaning in life and ego integrity, but I think we still need a deeper understanding of how individuals actually experience and construct these existential dimensions across different contexts. I'm particularly interested in what I refer to as existential health variables—things like meaning, coherence, and a sense of ego integrity—and how these emerge or evolve across the lifespan. To explore that, we need richer narratives, collected through qualitative methods, that capture the nuances of people’s lived experiences with aging, adversity, and identity.

People’s life stories and meaning-making processes are shaped not only by individual factors but by broader cultural and socioeconomic contexts. For instance, in my work with older adults and individuals experiencing homelessness, I’ve found that those who have faced significant hardship often have powerful, well-developed personal narratives—sometimes even more so than those who’ve lived relatively stable lives. That narrative structure may serve as a protective, meaning-making tool, especially for people who feel marginalized or devalued by society. Going forward, I’d love to see more work that integrates these personal stories into our broader theoretical frameworks. It’s through this kind of detailed, grounded inquiry that we can better understand what it means to live a meaningful life in all its complexity.

ISSEP: You’ve attended and presented research at our Existential Psychology Pre-conferences; how has your experience been with those?

Jon Sundby: I’ve had the opportunity to present at the Existential Psychology Pre-conference a couple of times virtually and this past year I was finally able to attend in person. I’ve always found this particular event to be uniquely inspiring. The existential psychology research community is incredibly engaged, curious, and grounded in a shared passion for existential questions, which makes for some of the most stimulating conversations I’ve had at any academic gathering.

“The existential psychology research community is incredibly engaged, curious, and grounded in a shared passion for existential questions, which makes for some of the most stimulating conversations I’ve had at any academic gathering.”

What I especially appreciate about the pre-conference is the collaborative atmosphere. My previous presentations were poster sessions, which I actually prefer over formal presentations sometimes. There's something about standing with others, exchanging ideas in a more informal and dynamic setting, that sparks creativity in a way that more structured formats often don’t. In fact, presenting my thesis work at the pre-conference led to some of the best feedback I received during that project. I was feeling somewhat discouraged at the time, as one of our key experimental manipulations hadn’t worked as expected. But having people engage deeply with the theoretical framework and share both their own experiences and suggestions was incredibly validating and energizing. It gave me a real boost—not just for the research itself, but for my motivation to keep pursuing it.

This year’s conference also featured some fantastic speakers, including Dr. Daryl Van Tongeren, whose work on religion, spirituality, and existential meaning I find particularly compelling. As someone who grew up with religion playing a subtle but persistent role in my life—my father is a pastor—his talk resonated with me. I think existential psychology has often emerged from a secular lens, rooted in philosophical traditions, but for many people, religion and spirituality are their primary tools for engaging with existential concerns. It’s encouraging to see that dimension being more fully explored in the field.

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Jon Sundby: One of the most important things I’ve learned is the value of staying curious and creative. Existential psychology is such a rich and compelling field, but it can be easy to lose sight of that when you're deep in the day-to-day grind of research, publishing, and academic pressures. Maintaining that sense of intellectual wonder—of being genuinely interested in the big questions—helps keep the work meaningful and prevents it from becoming just another task. My advice to future students would be to make space for that curiosity. Take breaks when you need to. Seek out conversations with others who are passionate about similar questions. And most importantly, regularly reflect on why you're doing this work in the first place.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the work/research context?

Jon Sundby: I live in Colorado so, unsurprisingly, I’m a big fan of the outdoors. With the mountains practically in my backyard, I spend a lot of time hiking, skiing, and camping—especially during the summer. Being outside is my go-to way to recharge.

Another big passion of mine is cooking. It’s my way of decompressing after a long day, and on quieter weekends I love diving into food experiments—things like making homemade kimchi or sauerkraut. My signature dish is paella, which I first fell in love with during a trip to Spain. I still try to recreate it, even though my tiny electric stove makes it a bit of a challenge!

Before the pandemic, I also traveled extensively. I taught English in China and Thailand and spent a year as a high school exchange student in Thailand, living a couple of hours north of Bangkok. That experience had a huge impact on me. Travel was a regular part of my life before graduate school, and now that things are settling down a bit, I’m starting to return to it. I have a trip planned to Mexico City soon, and I’m really looking forward to exploring more again.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music while working, what are you listening to lately?

Jon Sundby: When I’m writing or studying, I tend to gravitate toward instrumental music—something that helps me focus without the distraction of lyrics. Lately, I’ve been listening to Promises, a jazz album by Floating Points, Pharaoh Sanders, and the London Symphony Orchestra, that’s been really good to listen to while working.

When I need to unwind, I usually return to Nick Drake. His album Pink Moon is one I play on repeat when I want to decompress—it’s beautifully introspective and has this quiet emotional weight that I find really grounding.

As for a track recommendation, one that stands out recently is I Flirted with You All My Life by Vic Chesnutt. It’s a haunting, heartfelt song about the artist’s lifelong relationship with death, and it carries an added poignancy knowing his personal story. It’s a powerful listen and definitely resonates with the existential themes I find myself drawn to, both in research and in life.