Bored? Think your way out of hedonic adaptation

By Ed O’Brien, University of Chicago Booth School of Business. January 4, 2026.

New things are shiny and exciting, but in due time, our attention and attraction to them fade. We grow bored and turn to something new. And then we grow bored with that and turn to something else new. And then again. And then again. That wonderful new car smell? Soon it merely feels like your mundane ride to work. The thrill of unboxing this year’s new phone? Soon it merely feels like an outdated brick accumulating dust in your pocket. Rinse and repeat. Ad infinitum.

The chorus of Fuel’s Shimmer(1996) laments: “We're here and now / Will we ever be again? / 'Cause I have found / All that shimmers in this world is sure to fade away again”

This phenomenon has been formally studied for decades under the umbrella of hedonic adaptation. Hedonic adaptation is a robust and reliable feature of our mental machinery. It helps us function by maintaining homeostasis and motivating us toward growth and other goals. Yet it also paints a grim portrait of our abilities to sustain lasting happiness with the things we love at first glance. Indeed, it appears nothing gold can stay without a loss of shimmer—and there’s not much we can do about it.

But is this grim depiction true? In the current article, I review an emerging line of research from my laboratory suggesting that we can combat hedonic adaptation, without requiring people to abandon the thing itself (e.g., without having to take a break or seek novelty in the meantime). This emerging perspective on combating hedonic adaptation suggests promising interventions at the level of the perceiver’s construal; perhaps we can think ourselves out of hedonic adaptation.

I. Hedonic adaptation: The grim view

Hedonic adaptation refers to the psychological tendency for people’s hedonic reactions to grow less intense across repeated exposure to the same stimulus (Frederick & Loewenstein 1999; Wilson & Gilbert, 2008). Although this phenomenon applies to people’s responses to both good and bad experiences alike (Lyubomirsky, 2010)—such that people’s happiness from goodness fades over time, just as people’s misery from badness fades over time—in the current article I will discuss hedonic adaptation specifically through the lens of good experiences. That is, I focus on the question of why we can’t seem to stay happy for long, and how to combat that. If you’ve heard of the hedonic treadmill (Brickman & Campbell, 1971)—the metaphor that while people work to become happier, they ultimately stay in the same dissatisfied place—that’s what I study.

Hedonic adaptation is often compared to a treadmill—even as one “steps forward” one typically remains right the middle.

This idea that happiness fades, and good things normalize, has ample empirical support. In controlled laboratory settings, for example, experiments in the hedonic adaptation literature have repeatedly exposed people to many kinds of hedonic activities, such as re-playing the same fun game or re-watching the same fun video, and the typical pattern of results is that people’s enjoyment (and other such measures capturing people’s positive reactions) tends to decline (for reviews, see Alba & Williams 2013; Galak & Redden 2018).

Many mechanisms have been put forth to explain hedonic adaptation, with a primary one being something unavoidable about how we are biologically wired. Humans function better when maintaining homeostasis, meaning that whenever we experience a sudden change, our bodies and brains get to work figuring it out and thereby normalize it. As the logic goes, our responses to new happy events are no exception; while we enjoy an immediate jolt to happiness, the jolt awakens our defense to return to baseline.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the hedonic adaptation literature has come to paint a rather grim portrait of our abilities to sustain happiness over time. Good things grow old; people are doomed to boredom.

Consider the following grim descriptions from the literature: “What we miss is one simple thing: Once we have owned the car for a few weeks, other things will be on our minds while driving and we would feel just as well driving a cheaper alternative” (Schwarz & Xu, 2011, p. 144); “Hedonic adaptation can be resisted, but only with conscious, active efforts” (Lyubomirsky, 2010, p. 219); and “This point cannot be overstated: Every desirable experience is transitory” (Myers, 1992, p. 53). We’re hopelessly stuck on the treadmill.

Accordingly, resulting research on strategies for combating hedonic adaptation has traditionally focused on interventions that amount to abandoning the thing itself and enjoying novelty and variety in the meantime, so as to return feeling refreshed (e.g., taking breaks from enjoying something to combat one’s hedonic adaptation to it: Nelson & Meyvis, 2008; Quoidbach & Dunn, 2013; Sheldon et al., 2013). One may assume here that people are inevitably doomed to adapt otherwise, when stuck with the same old things.

II. A new view: Hedonic adaptation as a thinking problem

An exciting perspective has begun to emerge in the hedonic adaptation literature suggesting that this portrait may be incomplete. To be clear, there is certainly a ground truth to this grim portrait (for example, as best as we can tell, humans truly are wired for homeostasis). However, there may also be another side to the grim portrait that shows something more hopeful.

From this perspective, hedonic adaptation may also at least partly be constructed on the spot, just like any other psychological phenomenon (for reviews, see Hong & O’Brien, 2025; O’Brien, 2021). By dropping the deterministic (and biological) assumption that hedonic adaptation is hopeless and inevitable and instead adopting the assumption that hedonic adaptation may also be a “thinking problem” as well (i.e., we can modify our perceptions), this logic suggests that researchers can devise strategies for combating hedonic adaptation without requiring people to abandon things. In other words, perhaps some gold things might continue to “shimmer” if people are enabled to put their minds to making it so.

My laboratory is by no means the first to consider this perspective and put it to the test. For example, consider the fascinating finding that people who repeatedly practice active gratitude exercises often experience longer-term happiness from their current circumstances (e.g., Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2012)—which conceptually echoes the idea that the dulling effect of repeated exposure (i.e., hedonic adaptation) may partly depend on how people think about it. To highlight another example, there has been excellent research in recent years led by Jeff Galak and Joe Redden highlighting what they refer to as the “constructed nature of satiation”—meaning, how people’s experience of getting filled up (or not) from tasty foods can be influenced merely by people’s perceptions of getting filled up. For example, merely manipulating how much time seems to have passed since people’s last meal can make people feel more or less full, despite everyone eating the same amounts of the same foods at the same times (for a review, see Galak & Redden, 2018).

For the remainder of the current article, I will focus on findings like this that I know best—those coming out of my own laboratory. Specifically, I will highlight 3 key insights that we’ve observed thus far: (1) Hedonic adaptation is sometimes literally “just in one’s mind”; (2) Hedonic adaptation depends on people’s perceptions of the meaning of the activity; and (3) Hedonic adaptation depends on the novelty of the consumption context, even holding constant the literal consumption object.

1. Hedonic adaptation, but only in one’s mind

In one paper (O’Brien, 2019; see also Kardas et al., 2022; Klein & O’Brien, 2023), we found that people think that they will grow more bored by repetition as compared to how bored people actually end up growing in reality.

Counterclockwise from top: The Museum of Science and Industry near the University of Chicago campus; the “Genetics” exhibit at the museum; our research team collecting data as visitors exited the exhibit.

For example, in one experiment (O’Brien, 2019, Experiment 1), we sent research assistants to the Museum of Science and Industry, a popular science museum near the University of Chicago campus where I work. We set up a table right next to the Genetics exhibit, which features a variety of fun experiences that visitors can enjoy (e.g., visiting a station with incubating baby chicks, visiting a station explaining DNA cloning). We caught visitors right as they were exiting the exhibit, having naturally experienced it for themselves.

Based on random assignment, we asked some visitors to rate their enjoyment for their first visit, and to then predict their enjoyment for a repeat visit if they were instructed to go through it again right then and there. For other visitors, we asked them to rate their enjoyment for their first visit, and we then instructed them to actually go through the exhibit again right then and there; after, they returned to our table to rate their actual enjoyment for the repeat visit. All enjoyment ratings were made on a 1-7 scale such that higher ratings reflect greater enjoyment.

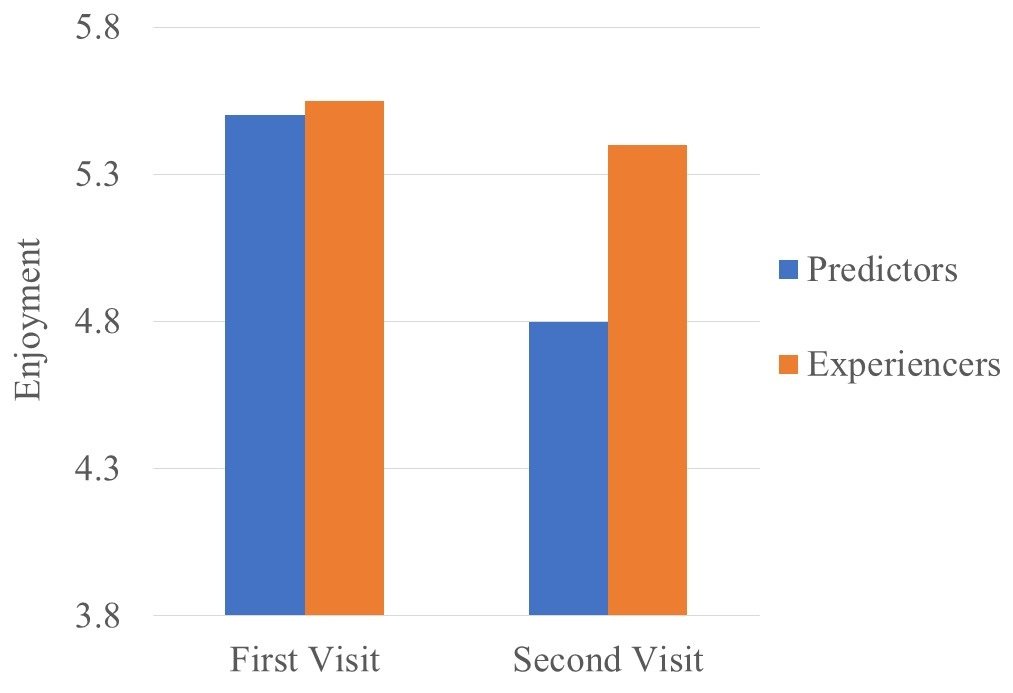

Figure 1 plots the results. As can be seen, visitors thought their first time going through the exhibit would be highly enjoyable—and here they were right. Yet visitors also thought that having to repeat that same exhibit would be duller by comparison—and here they were wrong. These findings suggest that we may be more worried about hedonic adaptation than is warranted.

Figure 1. Enjoyment for the exhibit at first and second visit, as a function of whether participants merely imagined the visit (“Predictors”) or whether they actually did the visit (“Experiencers”).

One reason for this effect (see paper for further details and discussion) is that, when imagining repetition, people can easily simulate the things they experienced from the first time around—but it is much harder for people to simulate the things they missed from the first time around, since, by definition, they missed them. When imagining repeating a museum exhibit, for example, what comes to mind are the parts of the exhibit that one can remember—and thus, as these parts play in one’s mind, the experience seems quite rote. Yet in reality, what happens at the repeat visit? People notice missed details, enjoy new things, make new interpretations, and so on, all of which render reality not so rote after all. Repeat experiences often prove “newer” than people can anticipate.

An important implication of this effect is that it leads people to make sub-optimal choices between novel activities vs. familiar ones. To stick with the museum example: people may pay up to access a brand new wing of an exhibit they’ve never seen before, as they may assume there’s little excitement left in repeating the same old things. In reality, however, repeating those same old things may prove quite exciting and entail ample opportunities for learning something new—which people could’ve enjoyed for free, without paying a premium.

2. Hedonic adaptation and perceived activity meaning

In another paper (O’Brien & Kassirer, 2019; see also O’Brien, 2022; O’Brien & Roney, 2017), we found that how quickly people grow bored of an activity depends on how people construe its meaning—even holding constant the activity itself. For example, in one experiment (O’Brien & Kassirer, 2019, Experiment 1), we gave participants $25 and instructed them to spend $5 every day, for the next 5 consecutive days.

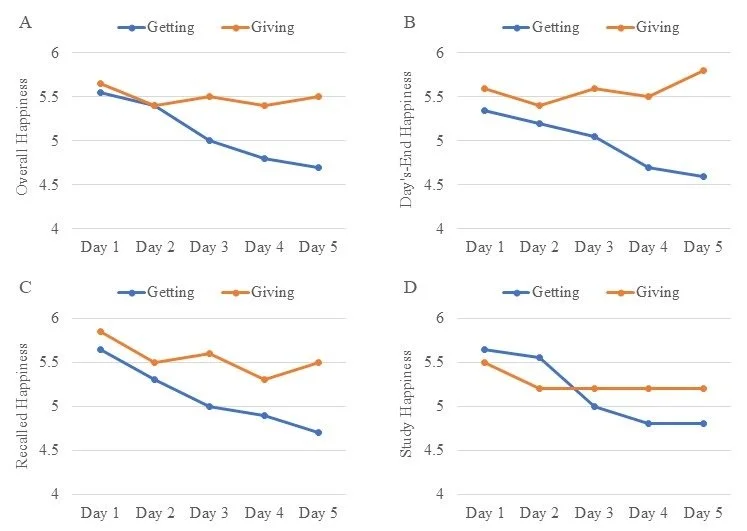

Figure 2. Happiness by day, as a function of participants’ spending condition. Mean ratings are plotted, with error bars showing ±1 SE. Panel A shows Overall Happiness, which is the average of Panel B (days-end happiness), Panel C (recalled happiness), and Panel D (study happiness).

Based on random assignment, we instructed some participants to spend it on a small treat for themselves, and that whatever they chose for Day 1, they should repeat this as identically as possible for the remaining days (e.g., many of these participants bought themselves the same coffee drink from their favorite café, for 5 days in a row). By contrast, we instructed other participants to spend the money on a small treat for others, and that whatever they chose for Day 1, they should repeat this as identically as possible too (e.g., many of these participants dropped the money into the tip jar at their favorite café, for 5 days in a row). Each evening, we texted participants a survey where they rated (a) their overall happiness for that day, which was an averaged measure of 3 dependent measures: (b) their day’s-end happiness at the point of that evening, (c) their recalled happiness at the time they spent the money, and (d) their happiness from the study so far. All happiness ratings were made on a 1-7 scale such that higher ratings reflect greater happiness.

Figure 2 plots the results. As can be seen, participants were slower to adapt to repeated giving than to repeated getting. The happiness we get from giving appears to sustain itself. This suggests a more hopeful view of hedonic adaptation than a strict deterministic view might depict. People’s mere perceptions of the meaning of an activity bear directly on their rates of adaptation.

A follow-up experiment (O’Brien & Kassirer, 2019, Experiment 2) replicated this idea under even more tightly controlled conditions, showing that participants were slower to adapt to repeatedly playing the exact same game merely when we framed the rewards they earned from that game as going to a meaningful charity of their choice, as opposed to earning the money for themselves. (And this was true; whatever earnings participants made, we sent that money to the given target.)

An important implication of this effect is that, if people need a more lasting boost to their well-being, there is a reliable answer here: helping others. It feels good the first time we help others, and as it turns out, it still feels good even after we help others repeatedly. Sustaining happiness over time really is possible—it depends on what we choose to fill our time doing.

3. Hedonic adaptation and novel contexts

Finally, in a third paper (O’Brien & Smith, 2019; see also Hagen & O’Brien, 2025; Winet & O’Brien, 2023), we found that people may be able to reignite their dulled enjoyment from hedonic adaptation simply by putting an old and dusty stimulus into a new consumption context. For example, in one experiment (O’Brien & Smith, 2019, Experiment 1), we conducted a taste test at our campus laboratory. The goal of the experiment was to have participants repeatedly eat the same old popcorn, so that we could track their self-reported enjoyment for the popcorn over the course of the taste test.

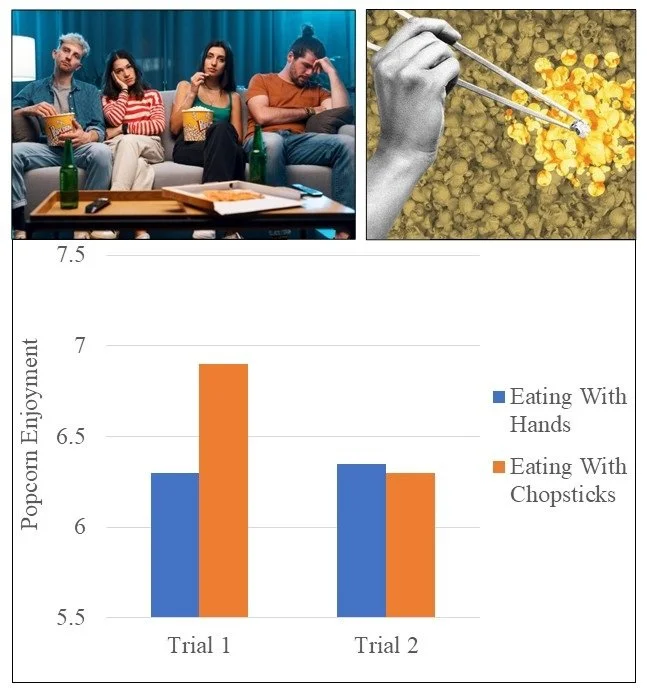

Figure 3. Enjoyment for the popcorn at Trial 1 and Trial 2, as a function of participants’ consumption-method condition.

Based on random assignment, we instructed some participants to eat the popcorn like they normally would: They picked up each kernel one-by-one simply using their hands. By contrast, we instructed other participants to eat the popcorn in a way that they had never done before (what we referred to as utilizing an “unconventional consumption method”): They picked up each kernel one-by-one using chopsticks (all participants had confirmed to us that they could use chopsticks, but had never before even thought of using them to eat popcorn).

Our experimental design was such that participants completed two trials of these procedures (henceforth “Trial 1” and “Trial 2”), with each trial containing many repeated bites within it. After each trial, participants rated their enjoyment specifically for the popcorn itself. All enjoyment ratings were made on a 1-9 scale such that higher ratings reflect greater enjoyment.

Figure 3 plots the results. As can be seen, participants at Trial 1 enjoyed the popcorn more when they ate it using chopsticks (i.e., when using the new unconventional method) vs. when they ate it using their hands (i.e., when using the same old method as always). As can also be seen, this relative boost to enjoyment from using chopsticks vs. hands went away at Trial 2.

These results suggest unconventional consumption methods can be used to combat hedonic adaptation, holding exposure constant. As we unpack in the paper, unconventional consumption methods invite people to adopt a “first-time” perspective, as if they are saying “I’ve done the activity before, but never like this”—which boosts immersion and enjoyment. In the popcorn experiment, we think this is why the boost critically went away at Trial 2—because the method was no longer novel. What mattered was people taking a “first-time” perspective, not something generally superior about chopsticks (or else we should’ve found Trial 2 boosts, too).

III. Concluding thoughts

Together, these findings—from my laboratory as well as other labs—shine light on an emerging and exciting perspective in the hedonic adaptation literature: things may not be as hopelessly grim as once thought. The next time you grow bored with something you love, try to fight the urge to think it is all over. There may be a lot more there to keep loving.

Dr. Ed O’Brien is an Associate Professor of Behavioral Science at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He earned his Ph.D. in Social Psychology from the University of Michigan as a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow, and a BS in psychology (summa cum laude) from Saint Joseph’s University with University Scholar distinction. He studies social cognition with a focus on temporal contexts, with particular interests in how people’s interpretations of change over time influence their cognition, emotion, and behavior. For example, in one line of work he studies how people's consumption enjoyment changes across repeat experiences and how this influences consumer behavior. In another line of work, he studies people's misperceptions of change over time and how this influences judgment and decision making. O’Brien's research is published in top business and psychology journals and is featured in major media outlets. He has won numerous research awards (e.g., ISSEP Best Paper Award, published in Consumer Psychology Review), career awards (e.g., APS Janet Taylor Spence Award for Transformative Early Career Contributions; SAGE Young Scholar Award; ISCON Early Career Award; APS Rising Star Award), and teaching awards (e.g., Poets & Quants Top 40 Under 40 Most Outstanding Business School Professors).