Uncertainty and compensatory trust in social connections

By Sandra Murray, University at Buffalo. January 3, 2026.

A positive element, a negative element, and a bond between the two. Philip Brickman (1987) identified this triad as the source of meaning in his book, Commitment, Conflict, and Caring. I read this book as a graduate student, and so, its details are hazy now but its core ideas continue to shape my research. Meaning, Brickman believed, comes from uncertainty. It comes from binding negative/uncertain aspects of our experiences to positive/certain ones. In relationships, for instance, Brickman argued that we love others because of their imperfections, not despite their imperfections. In other words, the very attributes that most vex us actually bind us to our significant others. The negative aspects of our experiences with our loved ones motivate us to value their positives all the more. Through this transformation, we come to see our commitment to others as sensible and meaningful—all part of the big story of why we need them in our lives.

Philip Brickman and his book, Commitment, Conflict, and Caring (1987).

Brickman’s ideas are really easy to see in my research on motivated cognition in romantic relationships. In the first article John Holmes and I published together, we reported two experiments that showed that people try to turn their romantic partner’s faults into virtues (Murray & Holmes, 1993). And a follow-up article showed that people in satisfying romantic relationships are really good at relationship-protective “yes, buts”—where they explain away their partner’s faults by tying them to greater virtues (Murray & Holmes, 1999).

Many years later, being a first-time parent inspired a line of research that showed we actually value our romantic partners more, not less, when they interfere with our goals (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). The backstory to this paper—as a new mom, I was shocked by the loss of my autonomy. It struck me that relationships with adults restrict autonomy too, but I had never really noticed that in my marriage. And that made me wonder why that would be the case—which brought me back to Brickman and the hypothesis that the autonomy costs that come with interdependence motivate us to value our romantic partners all the more—just like with kids.

Social safety nets

When I started thinking about what to write about in this piece, I realized that Brickman’s ideas are just as relevant to the research my collaborators, students, and I are doing now on “social safety.” This research aims to understand how people keep themselves feeling safe in social connections both inside and outside of romantic relationships.

We live immersed in multiple layers of social connections. Most immediately, we live connected to those closest to us—our romantic partners, children, friends, extended family, and neighbors. However, our social connections don’t end with the people we know. They extend to people we may never know—spanning out from neighbors, to one’s city/town, state/province, country, and ultimately, to the broader world.

These social connections differ in many ways, but they all share one feature. The actions other people take impact us and our actions impact them. That is probably one of the greatest lessons of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our choices affect each other. For instance, romantic partners can provide or withhold affection, new parents can share childcare more or less equally, siblings can be more or less competitive for parental attentions, community members can elect more or less fiscally cautious governments, and political leaders can govern more or less cooperatively. It is because others can both benefit and harm us that Baumeister and Leary (1995) argued that human survival depends on surrounding ourselves with safe (i.e., caring and protective) as opposed to unsafe (i.e., hurtful and exploitive) social connections (see also Kenrick et al., 2010).

To reap the potential benefits, and avoid the potential harms of social connection, we need to be mind-readers. That is, we need to coordinate our behavior with the behavior we expect of others. For instance, if Jamie could reliably anticipate when her partner Quinn was going to be good vs. ill-humored, her children were going to be cooperative vs. recalcitrant, her neighbors were going to be civic-minded vs. selfish, and her employer was going to be more fiscally cautious vs. optimistic, she could keep herself pretty safe. She could time social overtures to Quinn’s good humor, her children’s cooperativeness, her neighbors’ civic-mindedness, and her employer’s largesse.

But we are not mind-readers; we don’t have direct insight into the motivations of other individuals, groups, and institutions. This lack of insight makes social connection feel less than safe—which is not how we want to feel about social connection.

Now to get back to Brickman’s triad. As I reflected on this piece, I realized that the social safety regulation involves a triad too. At the broadest level, it involves mentally binding the potential to be hurt by others (the negative element) to the potential to be benefited by others (the positive element). In other words, we feel safe in social connection because of the potential to be hurt, not despite it.

This paradoxical idea is core to our thinking about how people regulate risk in romantic relationships (Murray & Pascuzzi, 2024). It’s also core to our thinking about how people regulate feelings of safety across personal and sociopolitical social connections (Murray, Lamarche et al., 2021; Murray, Seery et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2023). By personal social connections, I mean connections to close others, such as romantic partners, friends, children, and parents. By sociopolitical social connections, I mean connections to distal others, such as community members, political leaders, and government institutions. It’s this latter research on the social-safety system that I am going to highlight here given its expressed focus on existential uncertainty and meaning (Murray, 2025).

Uncertainty in Social Connections…

Building on what I said earlier, our theorizing on the social-safety system starts with this assumption: We humans feel safer in social connection when the individuals, social groups, or social institutions that have the power to impact our welfare behave as we expect. When others behave expectedly, it tells us that we understand their motivations well enough to adjust our behavior to keep ourselves safe. For instance, if Jamie knows that Quinn is always more good-humored after dinner than before, she can time her overtures to reap the best response from Quinn.

However, when the individuals, social groups, or social institutions that have the power to impact our welfare behave unexpectedly, it makes us question whether we really understand the motivations of others well enough to protect ourselves. In such situations, the social-safety system kicks in to give us new reason to feel safe in our social connections and continue counting on others. Metaphorically, this system works by bonding the negative element—the acute existential angst that comes from being surprised or taken aback by another’s behavior—to the positive element—the defensive attribution of greater safety elsewhere in our social connections.

For instance, when a romantic partner behaves unexpectedly (the negative element), this system keeps us feeling safe by motivating us to turn to the sociopolitical connections we share with others for safety (the positive element). Conversely, when fellow community members or national leaders behave unexpectedly (the negative element), this system keeps us feeling safe by motivating us to turn to the personal connections we share with others for safety (the positive element).

Compensatory Efforts to Maintain Safe Social Connections…

But why would a romantic partner’s unexpected behavior motivate people to turn to sociopolitical connections for safety rather than a different personal connection, such as a friend? This logic reflects our field’s thinking about how motivated or compensatory cognition works.

To satisfy desired goals, people change those cognitions that are least resistant, or most amenable, to change. So, when Quinn, Jamie’s romantic partner behaves unexpectedly, we think it is easier for Jamie to change her beliefs about the safety of sociopolitical than personal connections. This is because experiences depending on a romantic partner are mentally tied to experiences depending on children, in-laws, and family friends (Holt-Lundstad, 2018; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002). Similarly, experiences depending on fellow community members to behave in socially or legally prescribed ways are bound up in experiences depending on local, state, and federal officials and institutions to behave responsibly (Hudson, 2006).

Because of such interconnections, unexpected behavior by a spouse can put the motivations of friends and family in question as well, making it easier to change one’s beliefs about the safety of sociopolitical social connections (which are presumably less inherently related to other personal connections). Similarly, unexpected behavior by one’s community can put the motivations of government leaders in question as well, making it easier to change one’s beliefs about the safety of personal social connections.

However, to circle back to a point I raised earlier, unexpected behavior should be especially unnerving, and motivate people to turn elsewhere for safety, when people are more attuned to the power that others have to harm (vs. benefit) them. As an example, Jamie should be more unnerved by Quinn’s unexpectedly good-humor when she is more worried about Quinn’s commitment to her than if she was less worried. Jamie should also be more unnerved by her neighbor’s unexpected politics when she needs her neighbor’s help in raising funds to support their local school than when she doesn’t. In both of these examples, not being certain she fully understands someone who is in the position to harm (or benefit her), should motivate Jamie to look elsewhere in her network of social connections for safety. So, to sum up the theory, when our welfare is especially dependent on the actions of others, unexpected behavior is existentially unsettling and motivates us to look elsewhere in our social connections for safety.

Because our theory is grounded in real-world events, we test it in real-world situations by tracking participants across time in their daily lives. And whenever possible, we time our studies to capitalize on periods of heightened national uncertainty.

When Sociopolitical Social Connections Behave Unexpectedly…

In two daily diary studies (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), participants reported safety in personal social connections when they needed to quell the threat posed by national leaders behaving unexpectedly.

In two daily diary studies (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), we tracked unexpected behavior in sociopolitical social connections using real-world indices. We relied on (1) the VIX, the stock market “fear index” and (2) community-level Google searches pertaining to unexpected events in the national news. We measured vulnerability to being hurt by others through an individual difference—chronic trust in one’s romantic partner—given an abundance of evidence suggesting that less secure romantic relationship bonds make people feel more vulnerable to others. We expected participants who felt more vulnerable to being hurt to see greater safety in their family relationships on days after national leaders behaved more (vs. less) unexpectedly. That is, we expected such vulnerable participants to bind the negative element—unexpected national events—to the positive element—an especially loving and accepting family.

And that is what we found: Participants who usually struggled to trust their romantic partner defensively perceived greater evidence of their family member’s trustworthy and caring motivations on days after national leaders behaved more unexpectedly, as compared to days after they behaved more expectedly. That is, participants reported safety in personal social connections when they needed to quell the threat posed by national leaders behaving unexpectedly. No such effects emerged for participants who generally felt safer in social connection because they were absolutely certain they could trust their romantic partner.

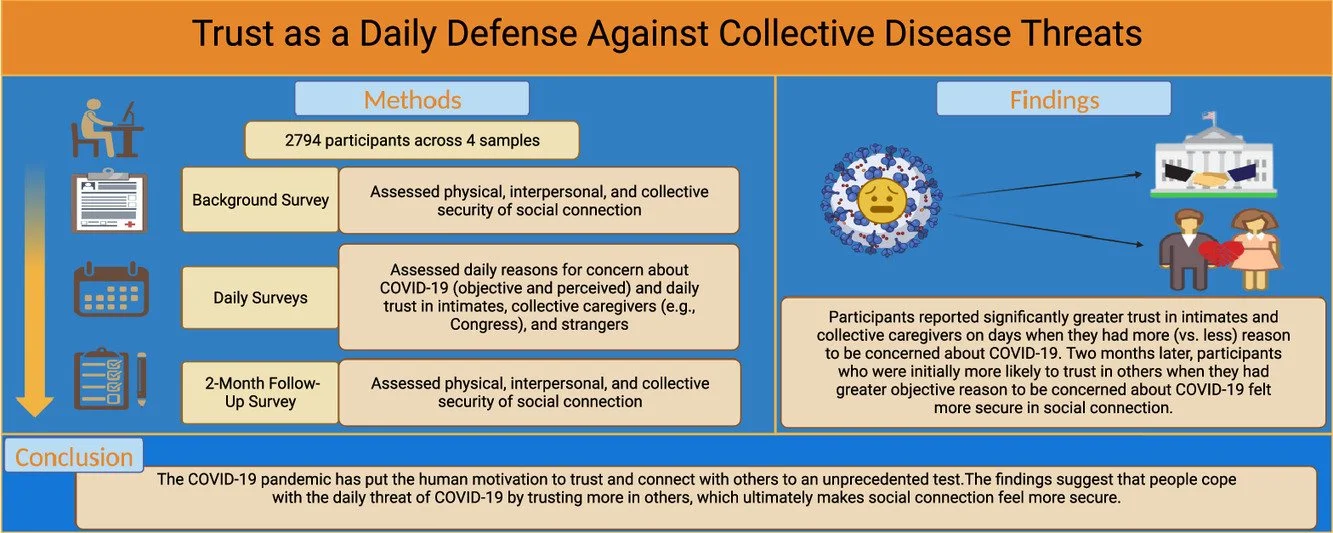

In a daily study of the COVID-19 pandemic (Murray, Xia, et al., 2022), participants reported greater faith in the blissful contentedness of their family relationships when on days when larger than usual increases in COVID-19 cases coincided with the nation voicing unexpected sentiments toward the President, as compared to days when it voiced expected sentiments.

In a further daily study of the COVID-19 pandemic (Murray, Xia, et al., 2022), we again tracked unexpected behavior in sociopolitical social connections using real-world indices. This time we tracked whether the nation’s collective impressions of the President were consistent with one’s own views (i.e., expected) or inconsistent with one’s own views (i.e., unexpected) on the assessment day. This time we measured vulnerability to being hurt by others through daily threats to physical safety—which we captured by larger (vs. smaller) daily increases in the number of COVID-19 cases nationwide. We expected participants who were facing greater acute risk of being physically infected by others to turn to their personal social connections for safety on days when the nation was behaving especially unexpectedly.

And that is what we found: Participants reported greater faith in the blissful contentedness of their family relationships when on days when larger than usual increases in COVID-19 cases coincided with the nation voicing unexpected sentiments toward the President, as compared to days when it voiced expected sentiments. In other words, participants found the safety they needed in their personal social connections to quell the safety threat posed by potentially infectious community members behaving unexpectedly. No such effects emerged on days when COVID-19 cases spread less rapidly (i.e., when there was low vulnerability).

When Personal Social Connections Behave Unexpectedly…

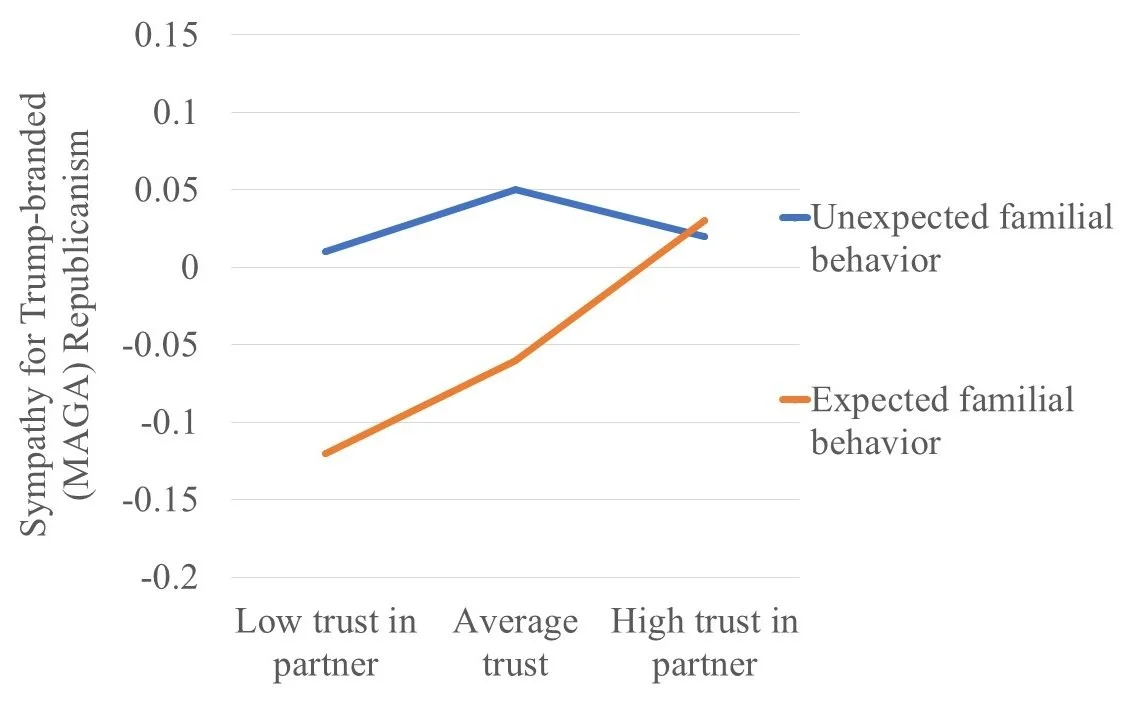

In a daily diary study (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), participants who usually struggled to trust their romantic partner trusted more in the President and government on days after they had less reason to feel safe depending on their family.

In a daily diary study (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), we tracked unexpected behavior in personal social connections by asking participants to report whether immediate family members (i.e., romantic partner, children) had said or done anything “out-of-the-ordinary”, “they did not expect”, or anything that “did not make sense” that day. We again measured vulnerability to being hurt by others through an individual difference—chronic trust in one’s romantic partner. We expected participants who felt more vulnerable to being hurt to see greater safety in the connections they shared with government leaders on days when family members behaved more (vs. less) unexpectedly. That is, we expected such participants to bind the negative element—unexpected family behavior—to the positive element—an especially wise, caring, and responsible government.

That’s what we found: Participants who usually struggled to trust their romantic partner trusted more in the President and government on days after they had less reason to feel safe depending on their family. That is, days after family members behaved more unexpectedly, as compared to days after they behaved less unexpectedly. In other words, when family members behaved unexpectedly, vulnerable participants found the evidence of safety in social connection they needed to see in the wisdom and good intentions of government and its leaders.

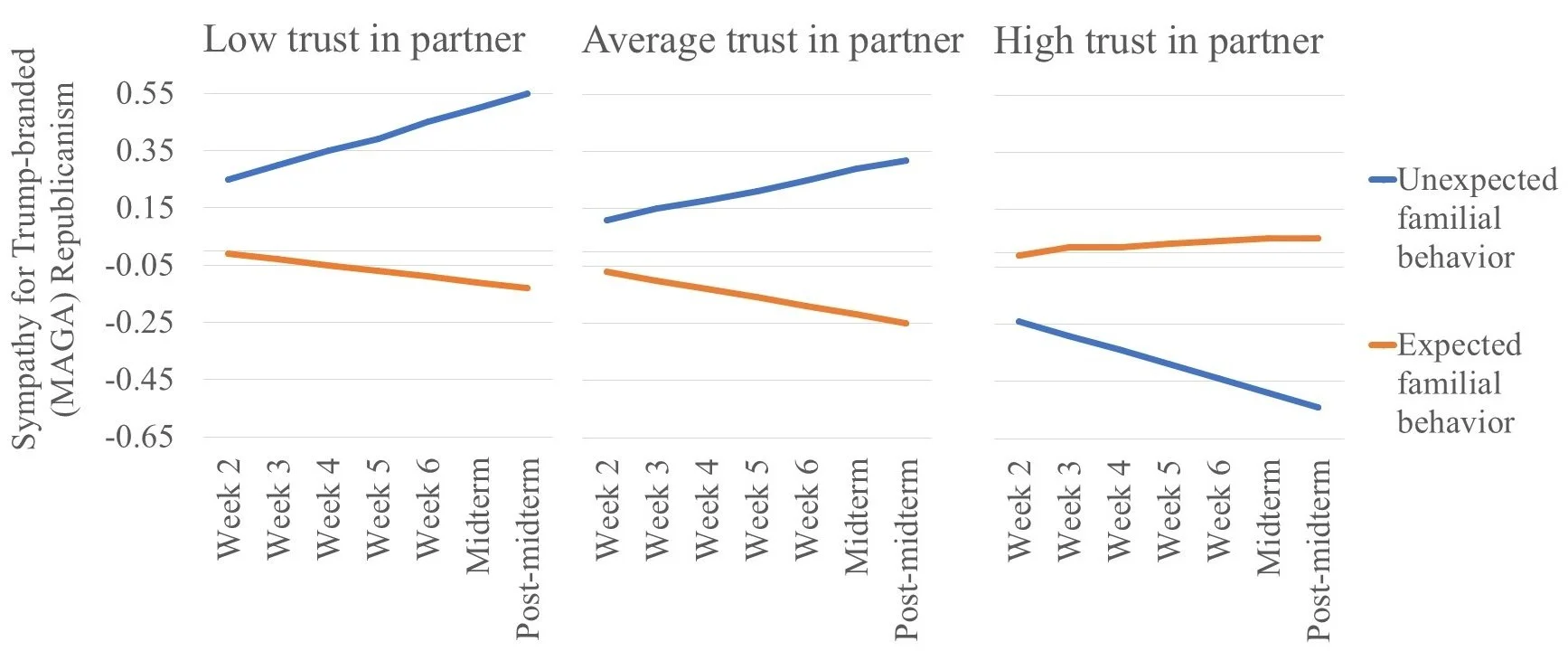

In a further weekly study of the 2018 midterm election in the United States (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), we again asked participants to report whether immediate family members (i.e., romantic partner, children) had said or done anything “out-of-the-ordinary”, “they did not expect”, or anything that “did not make sense” on the day of the assessment. This time we measured vulnerability to being hurt by others in two ways—through trust in one’s romantic partner and through the election itself.

In a weekly study of the 2018 midterm election in the United States (Murray, Lamarche, et al., 2021), participants who usually struggled to trust their romantic partner trusted more in the President and government on days when they had less reason to feel safe depending on their family.

With each passing week during the 2018 midterm election season, the public became increasingly aware of the eventual electoral result – Democrats gaining control of the House and Republicans retaining the Senate. Because neither party gained unilateral control of Congress on election day, we expected this result would make the risks of having one’s fate tied to the votes cast by fellow community members more salient to partisans of both stripes. Therefore, we expected participants who were less trusting of their romantic partner to be especially attuned to others’ capacity to hurt them after the results of the election were known. Post-election, we expected participants who felt more vulnerable to being hurt to see greater safety in the connections they shared with government leaders on days when family members behaved more (vs. less) unexpectedly. That is, we expected such vulnerable participants to bind the negative element—unexpected family behavior—to the positive element—an especially wise, caring, and responsible government.

That’s what we found: After the election, participants who usually struggled to trust their romantic partner trusted more in the President and government on days when they had less reason to feel safe depending on their family. That is, days when family members behaved more unexpectedly, as compared to days they behaved less unexpectedly.

These and other studies suggest that people’s desire to feel safe in social connection is intimately bound up in their quest to see meaning (i.e., expectedness) in the social world that surrounds them.

Author’s note. I am so grateful to the many collaborators who have been involved in these studies—Veronica Lamarche, Mark Seery, Jim McNulty, Dale Griffin, Ji Xia, Deborah Ward, Han Young Jung, David Dubois, Thomas Saltsman, and Lindsey Hicks.

Dr. Sandra Murray earned her Ph.D. at the University of Waterloo, working with John Holmes and Dale Griffin, followed by two years at the University of Michigan working with Phoebe Ellsworth and Norbert Schwarz. She is currently a researcher and professor of psychology at the University at Buffalo, and serves as Editor of the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (IRGP section). Her research generally examines how the motivations to (1) feel safe and protected against harm and (2) perceive meaning and value in the partner shape affect, cognition, and behavior in adult close relationships. Using the lens afforded by motivated cognition, she examines both the automatic and controlled processes implicated in the pursuit of safety and value goals. Her current research integrates relationship goal pursuits with the broader existential goal to perceive life as meaningful. This research assumes that perceptions of meaning in life depend on experiences inside and outside the relationship making sense. But because random everyday events can violate such expectations, people flexibly shift bases of meaning, finding compensatory order in the world when relationship experiences are nonsensical and finding compensatory order in the relationship when events in the world are nonsensical. Dr. Murray has received awards for her scholarly contributions from the International Society for the Study of Personal Relationships (ISSPR), the International Association of Relationships Research (IARR), the International Society for Self and Identity (ISSI), Society of Experimental Social Psychology (SESP), the Society for Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP), and the American Psychological Association (APA).