Uncertainty: When We Want to Know…and When We Don’t

By Jennifer L. Howell & Kate Sweeny

University of California, Merced & University of California, Riverside. August 1, 2025.

Imagine your doctor noticed something odd, and now you’re waiting to find out if you have cancer. How will you feel during the wait, and would you want to know or want to avoid knowing?

Imagine you go to the doctor for a routine visit. During the visit, she tells you she has noticed something odd in the examination and wants to biopsy and test a sample of tissue to rule out cancer. You get the biopsy, and the doctor sends the sample out for analysis. The office staff tells you it will take two days for the results to come in.

How do you think you will feel in those two days while you await your results? Will your mind return, again and again, to the possibility that you have cancer? Will you search the internet for information about prognosis and treatment? Will you try to distract yourself? Will you have trouble sleeping at night?

Now imagine that two days later, you get a voicemail from your doctor’s office telling you that they have your results and asking you to call them back. Do you call them back right away? What if you have fun plans that evening? What if you’re in a fight with your romantic partner—do you wait until you make up so they can be by your side? What if you don’t have health insurance and likely won’t be able to pay to treat the cancer, even if it is detected? Do you even bother calling back? Is it more stressful to not know or to hear bad news?

Alongside our colleagues, we have spent over a decade grappling with two fundamental impulses when it comes to learning information: one toward resolving uncertainty (knowing) and the other toward maintaining uncertainty (not knowing). We have studied when these impulses are most likely to arise and how they affect our thoughts, emotions, behavior, and well-being.

When We Want to Know

Wanting to know information, yet experiencing uncertainty while waiting to learn it, is an extremely common experience.

People often find themselves in situations where they desperately wish they could resolve their stressful uncertainty by learning some personally significant bit of information. Our opening biopsy example is one such case; other examples are waiting for news about a college or job application, waiting for your result on an important exam, waiting to see whether a hurricane will turn toward or away from your town, and countless others. In fact, when emotion researcher Ella Moeck at the University of Melbourne asked people if they were waiting to find out some kind of important news, 65% answered in the affirmative on any given day of her study (Moeck, unpublished data).

An early effort to understand these stressful experiences of not knowing was the uncertainty navigation model, which laid out a set of coping strategies people might use to manage their worry. That theory was useful for understanding what people do when they have to wait for some kind of uncertain outcome, but it had very little to say about why that kind of uncertainty is so stressful and why various coping strategies might be helpful.

Enter the EMO model, short for emotion-motivation-obstruction model (Sweeny & Howell, 2025). As we developed this new theoretical approach, one question drove our efforts: Why is waiting so hard? We ultimately identified a set of principles that come together to answer that question:

1. Worry is a natural response to personally relevant uncertainty.

2. Worry is great at motivating people to take action to protect themselves (e.g., worry about an upcoming exam motivating a person to study harder or worry about breast cancer motivating a person to get regular mammograms).

3. When we’re waiting for uncertain news, worry can’t do its motivational “job” because most opportunity for action is gone (e.g., worry about an exam after you’ve taken it or worry about a cancer diagnosis during the wait for biopsy results).

4. When worry gets stuck in the “on” position like that—unable to do its motivational “job”—health and well-being are likely to suffer.

We tested these initial ideas in a set of studies looking at worry about COVID-19 during the first year of the pandemic. We asked people how uncertain they felt about contracting the virus, how worried they were about it, and whether they felt like the had control over their COVID-19 risk, as well as some questions about their overall well-being. Sure enough, people who felt more uncertain also worried more, and those people also felt worse in general—but if they felt like they could do something to minimize their risk of contracting the virus, their worry wasn’t as harmful to their well-being (Howell et al., 2023). In other words, worry is only a problem when we can’t do anything to prevent the thing we’re worried about.

Aside from preparatory reappraisal (predemption), anxiety can motivate us to productively learn and prepare for a worrisome outcome, or we can productively distract ourselves such as when we slip into flow while playing music, video games, jogging, or even just scrolling social media on our phones.

So, then, what are we to do in those most worrisome of moments, when our fate is sealed but not yet revealed? The EMO model suggests two paths. One option is to simply worry less. Easy, right? Of course, it’s easier said than done, but our research has found a few ways to turn the volume down on worry when taking action isn’t an option.

First, you can think differently about your situation (officially called reappraisal) by considering silver linings in potential bad news. We call that predemption, and people are remarkably adept at it. In one study, 76% of women undergoing a breast biopsy following a suspicious mammogram—arguably awaiting some of the worst kind of potential bad news—said that some good would come of it if they were diagnosed with cancer (Rankin, Le, & Sweeny, 2020). In another set of studies, we found that engaging in predemption later buffered the blow of bad news (Rankin & Sweeny, 2022).

Alternatively, you could try to distract yourself from your worry, ideally by getting into a state of flow. Flow is a kind of exquisite distraction when your mind is completely focused on an activity such that the mind becomes quiet, time flies by, and worries melt away. We’ve found that flow bolsters well-being during the stressful wait for bar exam results (the exam people in the US take so they can practice law in a given state; Rankin, Walsh, & Sweeny, 2019) and during the stressful period of uncertainty that came along with the COVID-19 pandemic (Sweeny et al., 2020).

Another option is to harness worry’s natural motivation and use it to prepare for the possibility of bad news. Returning to the biopsy example, you could use the worrisome waiting period to get familiar with your insurance policy or the medical leave provisions at your job. You could also prepare mentally by bracing for the worst. Bracing is a kind of protective mental stance (like the psychological equivalent of bracing for impact) that embraces the possibility of bad news so it can’t catch you off-guard (Sweeny et al., 2006). Finally, you could make a plan to ensure that you’re able to cope with bad news if it arrives—perhaps by making sure you have loved ones nearby on the big day or a plan to go out with friends that evening, whether to commiserate or celebrate.

When We Don’t Want to Know

Sometimes, we just don’t want to know.

Although not knowing can be distressing when you’re waiting for uncertain news, there are also times when people would rather not learn information. This surprising preference for uncertainty appears in many domains.

For example, 85% of adults say that they would rather not know the time or circumstances of their death, even if they could (Gigerenzer & Garcia-Retamero, 2017), and about 40% of parents-to-be choose not to learn the sex of their child prior to birth (Shipp et al., 2004). People also avoid plot spoilers: 80% of participants in one study chose to avoid learning the ending of a story they were currently watching unfold (Pusey et al., 2021). People even avoid information that some might find surprising or unwise. In a study of romantic relationships, 34% of participants indicated that they would not want to know if their current romantic partner had cheated on them (Hussain et al., 2020), and in a representative sample of US adults, 39% indicated that they would rather not know their risk for cancer (Emanuel et al., 2015).

This decision to avoid available information—to maintain uncertainty—goes by many names, including deliberate ignorance (Hertwig & Engel, 2016), the ostrich effect (Karlsson et al., 2009), and, most prominently in psychology, information avoidance (Golman et al., 2017; Sweeny et al., 2010). We’ll stick with that term.

A few things differentiate information avoidance from simply not knowing something. First, the information has to be available. There are many things that people want to know that are fundamentally or temporarily unknowable (e.g., the time and circumstances of one’s death). Second, the person has to choose not to know the information, either by taking some action (e.g., deleting an email) or through intentional inaction (e.g., not opening an email). Such choices may entail conscious decisions (e.g., walking out of a room) or be more automatic (e.g., closing one’s eyes in response to something scary), but in all cases, information avoidance involves intentionally preventing oneself from learning available information.

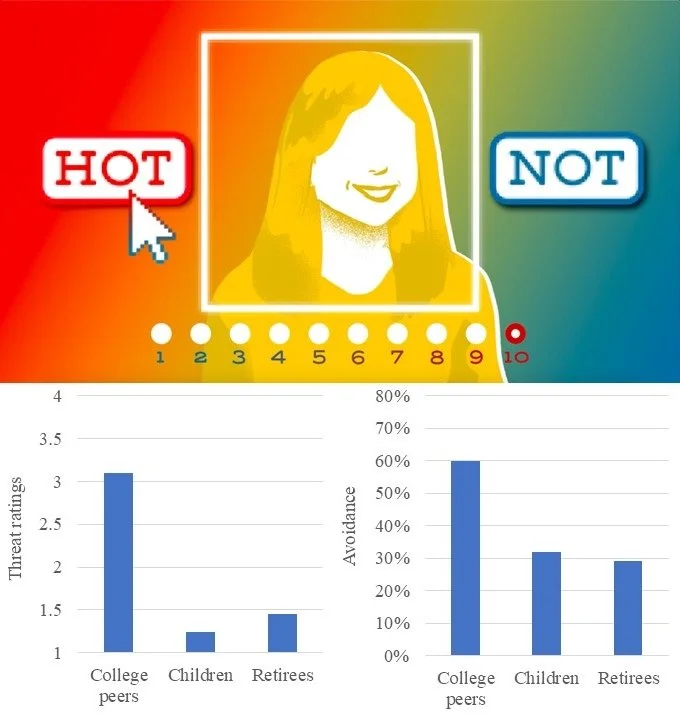

Upper: Participants were told five people would view their picture and rate their attractiveness on a 1-10 scale. Lower: Participants felt more threatened by the attractiveness ratings, and wanted to avoid seeing the ratings, when the raters were their college-age peers (vs. younger or older raters).

So why do people engage in information avoidance? In general, people avoid information if they believe it will negatively change how they think, feel, or behave, and if they believe they can’t cope with those changes (Howell et al., 2020). Starting with the first point, the more threatening information appears to be, the more likely people are to avoid it.

For example, one of our studies examined whether college students would avoid learning how attractive others found them to be—in other words, whether they were hot…or not. When students arrived for the study, we took their picture and then supposedly uploaded it so five other people could to rate it on a 1 to 10 scale of attractiveness (we actually deleted the photo). We told one group of students in the study that the people evaluating their attractiveness were other students on campus; we told the other group that the people evaluating their attractiveness were young children at a local elementary school. We figured that although no one wants to find out that kids think they’re unattractive, it would be far more threatening to learn that one’s peers (and thus one’s dating pool) had rejected them.

And our data confirmed that idea, such that students told us that it would be far more devastating to their self-image to learn that other students found them unattractive. About 15 minutes later, we told everyone that they could find out their ratings if they wanted to. Sure enough, we found that the group who thought they had been rated by their peers said “no thank you” to that information about 60% of the time, which was almost twice as frequently as those who thought they had been rated by children (Howell et al., 2019).

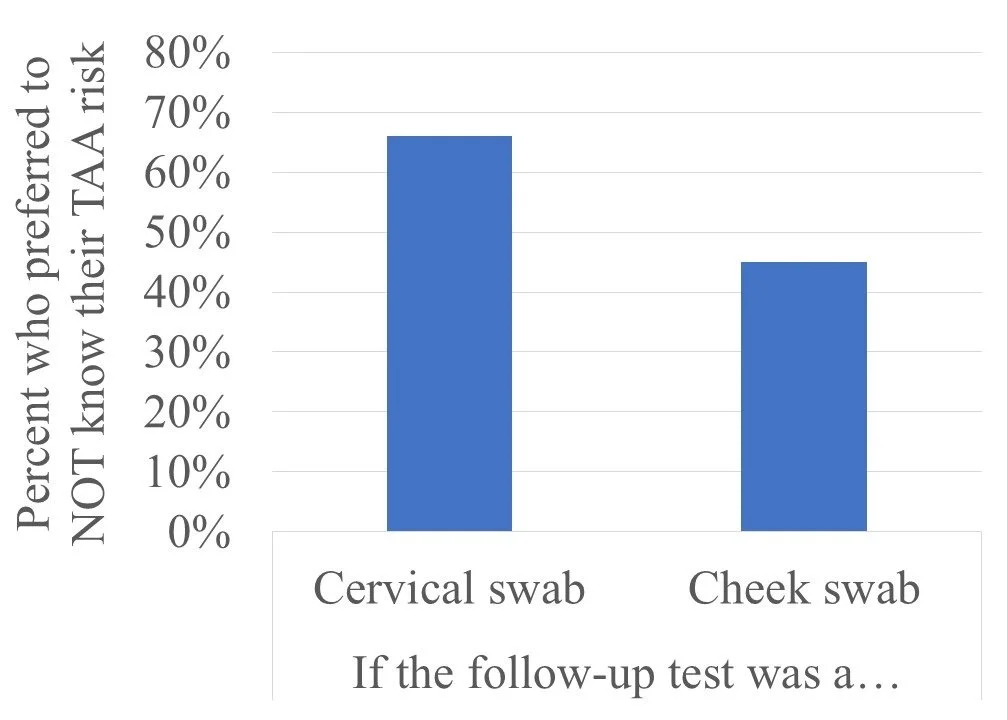

After watching this video about TAA Deficiency, participants completed a risk calculator and indicated whether they wanted to learn the results; if they were at-risk, they would need to undergo a follow-up test.

In another study (Howell & Shepperd, 2013), we tested whether people would avoid information if learning it might force them to do something they’d rather not do. We brought women into the lab and told them about a new disease called TAA Deficiency (the disease was made up, but they didn’t know that until after the study). We then told them that they could learn their risk for TAA Deficiency, but there was a catch: If they learned they were at high risk, they would have to undergo follow-up testing to see if they had the disease. We told one group of women that this follow-up testing was a simple cheek swab that could be done at the university hospital. We told the other group they would have to get a cervical swab at the university hospital to test for the disease.

Data from Study 1 (Howell & Shepperd, 2013), finding that people more frequently preferred to avoid learning their risk for TAA Deficiency, if being at-risk required a more invasive follow-up test.

Clearly, the cervical swab is both more unpleasant and more invasive, but would that unpleasantness be enough to prevent people from learning about their risk for a deadly disease? As our readers who have had to undergo a cervical swab may have guessed, it was. When the follow-up was a cheek swab, 45% of participants chose not to learn their risk; when the follow-up was a cervical swab, 66% of participants chose not to learn their risk.

Of course, it makes sense that people avoid information to avoid feeling bad about themselves or to get out of doing something unpleasant. But, if we always avoided threatening information, we’d miss a lot of what we need to know to survive and thrive. Fortunately, there’s a way people can look past some threats to learn hard truths: a sense that they can cope with whatever they might learn.

Our research suggests that when people feel like they can handle bad news, they’re more open to learning information. Most people have a host of psychological resources (e.g., resilience, optimism, self-complexity) and social resources (e.g., friends, family) they can turn to when they face bad news. They might focus on the positive, call a friend, or make a plan for how to succeed in the future. These resources and abilities, sometimes called threat-management resources, allow people to handle bad news in a productive way—and when people have those resources, they’re less likely to avoid threatening information (Howell et al., 2014; Hua & Howell, 2022).

Pulling it All Together

So, what should you do when you’re feeling uncertain, when you know there’s some information out there that you don’t already know? With everything we’ve learned about waiting, worry, threat, and information avoidance, we’d suggest asking yourself a few questions if you find yourself in that position.

First, is the information available right now? If the answer is no, the next question is whether there’s anything you can do to prevent a bad outcome or at least prepare for it. Run that checklist, then turn to the worry-management strategies we discussed earlier (e.g., distraction, predemption) or any other strategies that you find helpful in worrisome moments.

Second, if the information is available, you have another decision to make. You might ask yourself whether the information is likely to be useful, or if it’s only going to make you feel bad without any clear benefit. If the information might be useful, you could consider whether you’re able to cope with whatever you might learn; If yes, go for it, but, if the answer is no, it might be time to marshal your resources so that you can face the music.

Jennifer L. Howell is an Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Merced. She received her doctorate in social psychology from the University of Florida, where she developed her expertise in psychological-threat management and became a leading expert in research on information avoidance. She has received Early Career Awards from the Society of Behavioral Medicine, the Social Personality & Health Network, and the University of California, Merced campus, and she was named a Rising Star by the Association for Psychological Science. You can learn more about her research on her website and on Google Scholar.

Kate Sweeny is a Professor of Psychology and the Associate Dean for Graduate Academic Affairs at the University of California, Riverside. She received her doctorate in social psychology from the University of Florida. Her primary research focus for nearly two decades has been the stressful experience of awaiting important news. She has published more than 100 papers and chapters on waiting and related topics, which have collectively revealed complex and uniquely challenging dynamics of stress and coping during uncertain waiting periods. This work has been covered extensively in the media, including on NPR, on popular podcasts like Hidden Brain and Chasing Life with Sanjay Gupta, and in the New York Times and Washington Post. You can learn more about her research on her website and on Google Scholar.