Religious and non-religious paths to meaning in life

By Crystal Park, University of Connecticut. December 31, 2025.

Religious believers, such as Maddie, often derive a sense of meaning from their faith and struggle to see how other people could possibly experience meaning with any other worldview

A few years ago, in a discussion with undergraduate students about the research linking meaning in life with myriad mental and physical health benefits, I introduced findings from a paper on atheists’ meaning in life. Maddie, a very religiously devout student, literally jumped up from her seat. She blurted out, “Can atheists have meaning in life?” As we discussed the topic, many students said that they couldn’t imagine how a person could have a meaningful life without strong religious beliefs.

The students’ take on this issue surprised me, having studied meaning in life in many contexts over the years and learning about the many ways that people find meaning in their lives, religious or not. But Maddie had a point—my work and that of many others has shown a strong link between religiousness and meaning in life. So why is there such a strong connection between religiousness and meaning in life? And how do people without religion find meaning in life?

In this article, I sum up research conducted by our team and others on how religion often provides people with a robust framework for meaning—but also how nonreligious people draw on alternative sources to live meaningful lives.

The Human Need for Meaning

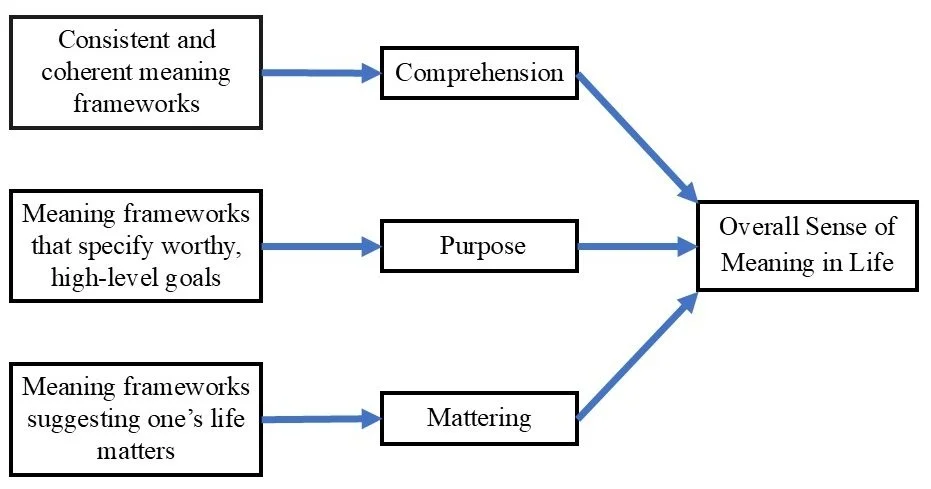

Meaning in life is a basic human need—just as vital to our well-being as food, safety, or shelter. At its heart, meaning refers to the subjective sense that life is coherent, purposeful, and significant. This feeling of meaningfulness involves understanding oneself and the world in a way that feels stable and predictable; having goals or aspirations that provide direction; and believing that one’s existence has value or impact. Thus, meaning in life is a complex feeling, made up of a sense of comprehensibility, mattering, and purpose.

Higher levels of life meaning is linked to greater life satisfaction, better physical and mental health, and even increased longevity.

People seek a meaningful life—they want to feel that what they do and experience makes sense, that their actions and thoughts are part of something greater and that their lives matter. Meaning in life is essential for psychological well-being and resilience. When people feel that their lives have purpose, coherence, and significance, they are better equipped to cope with stress, recover from adversity, and maintain a sense of motivation and direction.

Many studies have shown that higher levels of life meaning is linked to greater life satisfaction, better physical and mental health, and even increased longevity. Having a strong sense of meaning in life helps people navigate challenges by framing difficulties as part of a larger story or purpose and it provides a sense of stability and strength in the face of uncertainty. Further, aside from all of the physical, mental and social benefits that meaning is associated with, feeling a deep and consistent sense of meaning is centrally important in its own right. In short, high levels of meaning isn’t just a philosophical concept—it’s a practical foundation for—and key part of—living well.

Where does meaning in life come from?

People derive their sense of meaning in life from their underlying “meaning systems”—unique sets of beliefs about the world and personal goals that provide direction and significance. These systems include broad, foundational beliefs about how the world works and how one fits into it. For example, people hold beliefs about their own worth, about whether the world is generally fair or random, and about whether other people are trustworthy or benevolent (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). These beliefs help people make sense of their lives and experiences. These beliefs in large part determine one’s sense of meaning in life. When they are coherent and consistent, they provide a sense that life is understandable and manageable. They also support a feeling that one’s actions matter—for instance, by reinforcing the sense that one has a lasting impact on others or plays an important role in a community.

In addition to beliefs, people’s meaning systems also include their goals. These goals are ordered hierarchically, with a few ultimate, broad goals (e.g., be a good person, live a comfortable life, nurture my family, serve my community or country) that inform more proximal goals that extend down to the level of daily lifestyles (e.g., go to work today, pick up milk on the way home). The larger goals that people pursue are sometimes described as “sources of meaning” (Park et al., 2024), the life domains or values that individuals find most important. Working toward these goals and feeling that one is making satisfactory progress imbues life with a sense of direction and purpose. Some research has shown that having more sources of meaning is associated with having more meaning in life, and further, that some types of goals (e.g., being socially connected with others, serving God) are more likely to be associated with a higher sense of meaning in life than more externally-motivated goals such as pursuing wealth and power (e.g., Grouden & Jose, 2015; Park et al., 2025).

Meaning frameworks and meaning in life, as characterized by George and Park (2016).

People’s specific beliefs and goals along with their experiences in the world determine the degree to which they experience their lives as meaningful, and people vary greatly in how much they experience their lives as meaningful. Research suggests that people tend to feel a stronger sense of meaning when their beliefs help them make sense of their experiences, affirm that their lives matter in a broader context, and point them toward meaningful, high-level goals that reflect their deepest values and sense of identity (see Figure 1; George & Park, 2016).

To get a sense of Americans’ meaning in life, we conducted a survey study over the course of a year in a nationally representative sample of adults in the US. We found that about two-thirds of Americans have reasonably high meaning in life that is fairly stable over time, but about 20% had only modest levels of meaning in life and about 15% reported shockingly low levels (Park et al., in press). The reasons for these low levels are not clear; some have suggested connections between global secularization, which is an ongoing global trend (Kasselstrand et al., 2023) and observed increases in despair and mental health problems (Plante, 2024), but this potential association remains to be empirically tested.

Religiousness and Meaning

Returning to Maddie’s question—what role does religion play in maintaining a sense of meaning in life? Many religions espouse the notion that she expressed—that meaning in life is directly derived from religion and without it, there is no meaning. Reflecting this notion, many research studies from around the world have demonstrated robust links between religiousness and meaning in life (Park, 2013). In another recent study of a nationally representative sample of adults across the United States, we found that the more someone reported relying on religion to make sense of the world, on average, the higher their sense of meaning in life (Park et al., 2024).

Another line of research examining religion and meaning involves comparing the average levels of meaning in life of atheists and people who believe in God. Findings from these studies also highlight the link between religiousness in meaning in life: Atheists typically report lower levels of meaning in life (e.g., Abeyta & Routledge, 2018; Cranney, 2013; Edgell et al., 2023: Hayward et al., 2016; Horning et al., 2011; Prinzing et al., 2023; Schnell & Keenan, 2011). For example, recent surveys of national US and German samples found that believers reported higher meaning in life than did atheists (Nelson et al., 2021; Park et al., 2025; Schnell & Keenan, 2011).

Why is Religion So Effective at Promoting Meaning in Life?

Psychologists have proposed many ideas regarding why religion may promote higher levels of meaning in life.

Taken together, these elements—coherent worldview, answers to big questions, moral clarity, transcendence, resilience in suffering, and community—form a powerful meaning system that makes religion especially effective at helping people experience their lives as meaningful (Park et al., 2025).

One common idea is that religion offers global beliefs that form a coherent worldview. At its core, religion provides a comprehensive story about the world—why it exists, what our place in it is, and how we should live. These are some of the deepest questions human beings ask, and religion answers them in ways that are emotionally powerful. When life is difficult or chaotic, religion’s story can offer a stabilizing perspective. Whether through beliefs in ultimate fairness and justice, divine purpose in the universe, moral teachings, or conceptions of an afterlife, religion gives people a framework that helps make sense of both the joys and sorrows of life.

Religion also answers fundamental existential questions that many other belief systems avoid or leave open-ended. Why are we here? What is our purpose? What happens after we die? What is the nature of good and evil? These questions can be unsettling when left unanswered, and secular sources often provide more ambiguous or shifting responses. Religion, in contrast, tends to offer clearer, more definitive answers that reduce existential anxiety and foster a sense of orientation and direction. Having a firm grounding in these core beliefs can help people feel less lost and more at home in the universe.

Another crucial way religion supports meaning in life is through its moral and ethical guidance to people as they pursue their ultimate goals. Most religious traditions articulate a strong set of values and codes of conduct. These values don’t just tell people how to behave—they provide a vision of the kind of person one should strive to be. This moral clarity helps guide people in their pursuit of long-term goals, whether those involve serving others, raising children, or pursuing spiritual growth. Having a clear sense of what is right and important helps individuals live with integrity and enhances the sense of purpose they experience in pursuing their goals.

Religious beliefs also often include a call to transcendence—to reach beyond oneself and connect with something greater. Whether through prayer, service, or mystical experience, religion encourages people to focus not only on personal success or happiness but on relationships with others, the natural world, or the divine. This move away from self-centeredness is a common thread in many accounts of meaningful lives. It helps individuals find fulfillment in contributing to others or aligning their lives with a higher calling. In this way, transcendence enriches meaning by expanding the scope of one’s life beyond individual circumstances.

Importantly, religion plays a profound role in helping people make sense of suffering. Life is full of pain, disappointment, and loss, and one of religion’s greatest strengths is its capacity to help people interpret and endure these experiences. Many religious traditions frame suffering as redemptive or purposeful—something that contributes to spiritual growth, builds character, or fits into a divine plan. Others offer the promise of eventual justice or restoration, whether in this life or the next. These beliefs can provide comfort and resilience during difficult times, giving people a sense that their suffering is not in vain but part of a larger, meaningful narrative.

Finally, religion often provides a sense of community and belonging—another essential ingredient in a meaningful life. Religious communities bring people together with shared beliefs, rituals, and values. These social connections foster support, accountability, and a shared sense of identity, sources of meaning that greatly enhance one’s sense of meaning in life. Many religious people also experience a close attachment to and relationship with God. Being part of something larger than oneself—whether that’s a congregation, a tradition, or a spiritual lineage—helps individuals feel less isolated and more deeply connected to the fabric of human life; this connection reinforces their sense that their lives matter.

Taken together, these elements—coherent worldview, answers to big questions, moral clarity, transcendence, resilience in suffering, and community—form a powerful meaning system that makes religion especially effective at helping people experience their lives as meaningful (Park et al., 2025). While not everyone finds meaning through religion, for billions of people throughout history and today, it remains one of the richest and most enduring sources of coherence, purpose, and significance.

Meaning in Life for the Non-Religious

While religion offers a particularly rich and multifaceted framework of global meaning, it is by no means the only framework through which people can make sense of the world and find direction and purpose. For example, some researchers have discussed alternatives, such as science. However, the extent to which non-religious, non-metaphysical frameworks can address issues of ultimate purpose and existence may be limited (Vail et al., 2010) and people often find such non-metaphysical viewpoints unsatisfactory. In our national survey of U.S. adults, we found that relying on science to make sense of the world was unrelated to meaning in life (Park et al., 2024).

Philosophical worldviews, humanism, and even deeply held personal principles can provide some of the same core ingredients that make religion so effective: a coherent understanding of the world, a sense of purpose and mattering, a feeling of belonging, and opportunities for transcendence.

Yet individuals—both religious and non-religious—hold many additional beliefs besides those that are religious that help them make sense of the world and draw meaning from secular sources of meaning such as close relationships, creative pursuits, achievement, adventure, civic engagement, or commitment to a cause larger than themselves—such as social justice, environmental stewardship, or scientific discovery. However, the evidence suggests that the meaning systems of religious people may differ from those of non-believers in ways that disadvantage them in finding meaning even from secular sources (Nelson et al., 2021). For example, several recent studies including our US national survey found that atheists found less meaning in many secular sources (e.g., relationships, family, achievement) than believers. Further, we found that atheists have lower beliefs in benevolence of the world and other people, controllability of the world and themselves, and a just world, and higher beliefs in randomness (Park et al., 2025). A group often referred to as “spiritual but not religious” has received increasing research attention in recent years (Wixwat & Saucier, 2021); research examining their average levels of meaning in life might shed light on how nonreligious spirituality is associated with living a meaningful life.

Still, philosophical worldviews, humanism, and even deeply held personal principles can provide some of the same core ingredients that make religion so effective: a coherent understanding of the world, a sense of purpose and mattering, a feeling of belonging, and opportunities for transcendence. In fact, people who are not religious can also experience high levels of meaning in life, especially when they are deeply connected to their values and feel that their lives contribute to something beyond themselves (Park et al., 2025). Meaning, in other words, is a universal human need that can be met in diverse and deeply personal ways—religious or otherwise.

Frank Bruni, American journalist and New York Times columnist since 1995.

In relaying his experience as the sole non-religious member of a panel, Frank Bruni (2025) recently captured the potential of non-religious spirituality as a source of meaning in his life:

“Where, absent religion, did I find meaning in life? That question wasn’t put to me in exactly those words. But it was the gist of many of the prompts that came my way, and I struggled to respond to them, maybe because the audience’s skepticism about me was palpable, maybe because the hour was late. . . I find meaning in a catchy melody. I find meaning in an artful turn of phrase. I find it in an entirely unnecessary kindness that I extend to someone or a wholly volitional gesture of courtesy that someone extends to me. I guess I’m saying that I find meaning in beauty — in our instinct and ability to fashion moments of grace that have nothing to do with survival and everything to do with transcendence…I realize how close to God-speak that sounds. But aren’t at least a few of the differences between the overtly religious and the obliquely spiritual matters of metaphor and vocabulary? I believe that this consciousness of ours and these lives we lead are grander than our most basic needs and most urgent desires. That conviction can be wrapped in or uncoupled from an elaborate mythology. In either case, it’s a gateway to joy and a portal to peace.”

Bruni provides a moving perspective on how meaning can be found "absent religion" through beauty, kindness, and moments of grace, and reflects on how this consciousness points towards something "grander" without invoking the divine.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the search for meaning is a deeply human endeavor—one that transcends religious commitments, worldview, or background. Religion has long offered a profound and enduring structure for meeting this need, providing identities, stories, goals and values, relationships, and rituals that help people make sense of their experiences, shape their lives and feel that they matter. But as we’ve seen, people without religious belief are not left adrift. They, too, can and do build meaningful lives—sometimes by weaving together sources like love, learning, beauty, justice, and personal growth into their own unique frameworks of meaning.

What matters most is not whether one is religious or secular, but whether one’s beliefs and goals form a coherent whole that answers life’s biggest questions, offers purpose and direction, and affirms that one’s life is significant. Meaning in life is not, as Maddie had thought, reserved exclusively for the devout—it is open to anyone willing to reflect deeply, live with intention, and connect with something beyond the self. Whether through the language of faith or of values, of God or of grace, the human spirit continues to seek and find meaning in ways as diverse and rich as humanity itself.

Dr. Crystal Park is a researcher and professor of psychology at the University of Connecticut. Her research focuses on stress, coping, and adaptation, particularly on how people’s beliefs, goals, and values affect their ways of perceiving and dealing with stressful events. She has developed a comprehensive model of meaning and meaning making and is an expert in the psychology of religion and spirituality, with over 350 scientific papers and six books on the topic. Dr. Park is a Fellow of the American Psychological Association (APA) and a former president of Division 36 of APA (Psychology of Religion) and recipient of their Early Career Award. In 2014, she received the William James Award from Division 36 in recognition of her contributions to the psychology of religion and spirituality.