Bao Han Tran on Time Perception and Overcoming Social Pain

Bao Han Tran is a Ph.D. student in Experimental Psychology at Texas Christian University, having earned her B.S. from the University of Houston in 2022. Her research draws from existential psychology to examine how our perception of time, both as a sensory experience and as a cognitive orientation, shapes psychological well-being. She is particularly interested in how temporal experience intersects with close relationships, self-identity, group dynamics, and language. Bao Han’s current projects examine how time perception influences the pace of social healing, the relationship between time perspective and authenticity in older adulthood, and how temporal rootedness manifests among individuals with a history of substance use. More broadly, her work asks how our subjective experience of time contributes to individual flourishing and collective resilience. Outside of the lab, Bao Han enjoys discovering new coffee shops, reading widely, and getting lost in a good book.

Bao Han on the web: Lab Website | Personal Website

By Nicholas Kelley, University of Southampton. August 12, 2025

ISSEP: How did you first become interested in existential psychology?

A fundamental interest in real-world meaning and morality, addressed on the one hand via ancient religious beliefs and supernatural ideas and on the other hand via modern psychological science and natural world phenomena.

Bao Han Tran: I think my interest in existential psychology really grew out of my upbringing in the Catholic Church. I was very focused on questions of right and wrong, morality, and trying to live according to those principles. As I matured, though, I found that some of the moral questions I wrestled with weren't fully answered in a way that felt satisfactory to me. I was empathetic and deeply concerned with these moral issues, but there was a sense that something was missing.

When I got to high school and college, I discovered psychology, and it started to answer a lot of those questions about meaning, morality, and human experience that I had been pondering. I also grew to love the research process during that time, which deepened my engagement. During this time, my relationship with religion became more complicated. I transitioned away from being as religious as I once was, which led me to a more nuanced and compassionate understanding of myself and others, including my own struggles with faith. So, my path to existential psychology was shaped by this intersection of religion, morality, and a desire for deeper understanding. Psychology offered a way to explore those questions in a meaningful, scientific way.

ISSEP: You’ve been doing some great research in existential psychology lately. Can you tell us more about your work?

Bao Han Tran: At SPSP I presented a project on how time perception influences recovery from social pain. Social pain, like the kind we feel after rejection, is associated with a range of negative outcomes such as lethargy, emotional numbness, feelings of meaninglessness, and avoidance of self-awareness. This is the state known as "cognitive deconstruction," which slows down how we perceive the passage of time (Twenge et al., 2003).

Interestingly, time perception has been shown to affect the rate of physical healing. When people feel like time is moving faster, their bodies tend to heal more quickly (Aungle & Langer, 2023). Because physical and social pain share some of the same neural pathways (Eisenberger et al., 2012), we wanted to explore whether this pattern would extend to emotional healing. Specifically, we tested whether differences in time perception affected how quickly people recovered from social pain.

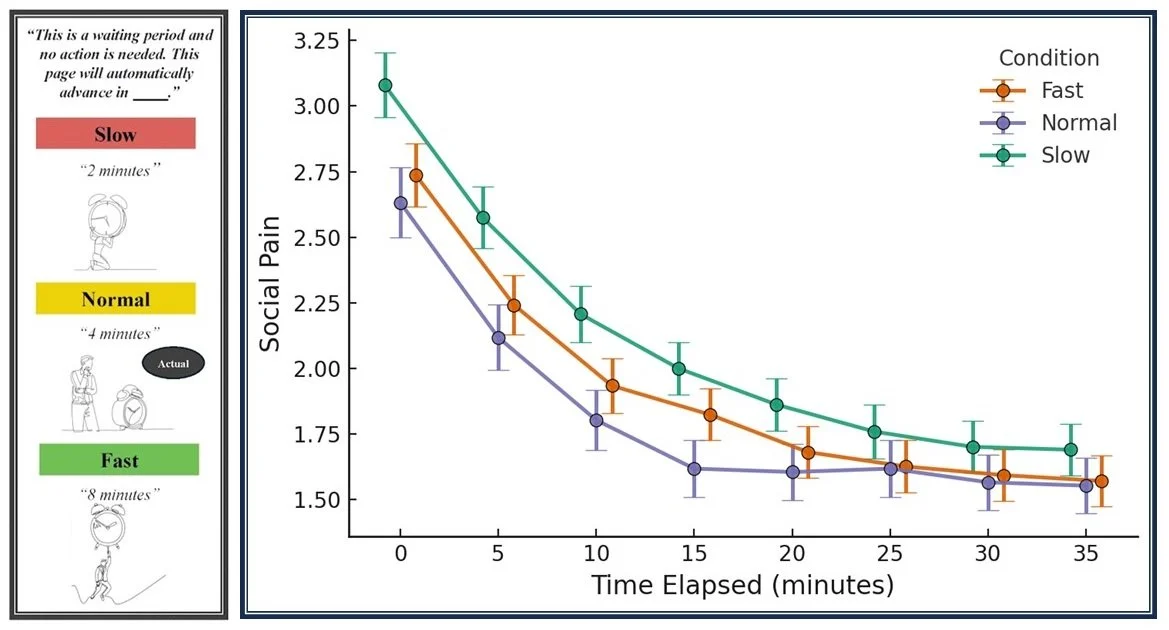

All participants reflected on social rejection for 4 minutes, but were made to feel the time had passed either slowly, normally, or fast. Then, they reported their willingness to re-engage with others and their felt emotional pain after each of 7 five-minute waiting periods. Participants’ emotional pain lasted longer if they perceived slower passage of time while reflecting on their rejection.

In my experiment, participants (N = 261) first wrote about a personal experience of social rejection and the emotions that came with it. Then they were randomly assigned to experienced one of the following time perception conditions: a slow condition where they were told only 2 minutes had passed, a normal condition where they were told 4 minutes had passed, and a fast condition where they were told 8 minutes had passed. In reality, 4 minutes passed for everyone.

After that, we asked participants about their pain from the memory and willingness to re-engage in social interaction immediately and again after each waiting period, for seven cycles. Participants in the slow condition reported a more prolonged recovery from social pain. Although their willingness to re-engage with others did not change among the groups, their felt pain from the memory lasted longer (in real time) in the perceptually slow compared the normal and fast conditions. This suggests that when time feels like it is dragging, emotional pain feels more intense, and healing takes longer. Our findings show that subjective experiences of time can shape emotional recovery and may have important implications for mental health support.

ISSEP: Fascinating! How did you develop your interests in this topic area?

“I’m curious if slowing down time, or changing how we perceive it, might help people reflect more deeply and find meaning, even in difficult or mundane experiences. Maybe that’s part of why stressful or painful moments sometimes stick with us—because they feel longer or more intense, giving us a chance to extract meaning from them.”

Bao Han Tran: Honestly, it’s a really personal journey for me. I am a recovering perfectionist. During college, I used to overschedule myself and constantly try to build the best CV possible. I felt like I had to be productive every minute of the day. I didn’t even realize this would be my area until I graduated. Over time, I went through a lot of self-growth and started questioning why people stress so much about time and productivity. For me, the pressure was internal. Nobody was telling me I didn’t have enough time, but I still felt that way. I realized I needed to live more in the present because I was always focused on the future, thinking, “I need to do this so I can get into graduate school.” Then I began thinking about the health costs of that kind of productivity mindset. Focusing so much on future goals could come at the expense of health, and that raised even more questions I didn’t have answers to.

My own timeline was unusual, in part because of COVID. I started at community college, which felt like a normal pace, then went on a fast track and graduated in three years. But because of the pandemic, I was only physically on campus for about a year, and I took a gap year focused on research and side work. During that time, I often felt like I wasn’t where I was supposed to be and that I should have already been in graduate school. That feeling of falling behind, even when I was working hard, made me think more about how we experience time subjectively, especially when external circumstances disrupt our plans.

I also wonder about how our experience of time, especially when it feels like it’s going too fast, relates to how meaningful things feel. Sometimes, when time seems to slow down, even everyday moments can feel richer or more significant. For example, I love doing things that take time, like reading a physical book or making art, where I can really savour the experience. I’m curious if slowing down time, or changing how we perceive it, might help people reflect more deeply and find meaning, even in difficult or mundane experiences. Maybe that’s part of why stressful or painful moments sometimes stick with us—because they feel longer or more intense, giving us a chance to extract meaning from them. It’s an idea I’d love to explore further, especially how these time perceptions might interact with how people cope with challenges or savour positive experiences.

ISSEP: Do you see your research topic being dealt with in art or culture, and can it help us make sense of important human experiences or cultural or technological trends?

Bao Han Tran: Our experience of time is central to how we understand ourselves and the world around us. The way we perceive the past, present, and future shapes our emotions, behaviors, and how we find meaning in everyday life. My research shows that when time feels slow or fast, it changes how we recover from social pain, how we engage with others, and how meaningful moments feel.

This idea is captured beautifully in the A24 film We Live in Time (2024) with Andrew Garfield and Florence Pugh. It explores what it means to live fully in the present, especially when time feels fragile. It reminds us that time is not just something we measure, but something we feel. On the other hand, the film Click (2006), starring Adam Sandler, offers a different but equally relevant perspective. It shows what happens when we try to fast-forward through life’s painful or boring parts and only dwell in the good ones. Both films speak to a core insight from my research: our perception of time can change how we experience life’s highs and lows.

These cultural moments echo a larger truth. In today’s world, technology often speeds up life. Social media, instant communication, and tools designed to save time can warp our sense of presence. This has real consequences for mental health, relationships, and how we experience meaning. When time is rushed, moments can lose their weight. When time slows, even difficult experiences can feel more profound and transformative. By uncovering how time perception influences emotional healing, my work offers insights for how people might cope with distress, build resilience, and reconnect with others. It helps explain why some events feel unforgettable while others blur into the background. It also gives us a lens for understanding why certain cultural trends, stories, or artworks resonate at a deep emotional level. Studying how we live through time, not just in minutes and hours but in moments of connection and feeling, helps bridge individual psychology with the broader rhythms of culture and change. It offers a way to understand what it means to be human in a fast-moving world.

ISSEP: What do you think are some of the remaining issues or important next steps toward better understanding time perception?

Bao Han Tran: One of the biggest challenges is that time is such an abstract concept. When people reflect on their sense of time, they have to draw on their current life circumstances, their emotions, and their environments. That makes it difficult to study using just quantitative methods. We need more qualitative data to truly capture how people live through time. It is not enough to know they think about it in the abstract, but how they experience it in moments of grief, connection, or transition is important too.

Another step forward is encouraging more researchers to consider how time shows up in their own work. It’s a factor in so many areas: clinical psychology, cognitive science, health, social psychology, and even education. But right now, the field is very fragmented. When I was looking at graduate programs, I searched for labs that focused on time. I didn’t find many. There are a few researchers, like Zimbardo with his time perspective scale, or scholars like Dr. Małgorzata Sobol-Sikorska at the University of Warsaw, who is doing fascinating work on how time perspective shapes health and even dental anxiety. But there is no centralized community yet. That can feel isolating, but it also means there’s room to build something new.

At a deeper level, we need to better understand the mechanisms underlying time perception. One challenge I’ve noticed is the lack of standard methods to measure subjective time perception. For example, participants can be asked to make prospective or retrospective judgments about how much time has passed, but these approaches are limited by heuristics and cognitive biases. What is the best method to control for these if it is even possible? I’m also curious about how subjective time relates to biology. Although we have circadian rhythms and neural systems that track objective time, our lived experience of time often feels very different. How these biological systems interact with our subjective perception remains an open question.

Finally, I’m becoming more interested in how evolutionary psychology fits into this. Ideas from life history theory suggest that people might develop fast or slow orientations to life based on their early environments. That orientation might affect how they experience time, how they manage stress, and even how their immune systems function. There is so much more to explore. Ultimately, I think what’s uniquely human is not just our ability to track time, but our tendency to reflect on it, to revisit and reframe it, and to build meaning through it. That’s what makes time perception such a rich and essential area of study.

ISSEP: You’ve attended and presented research at our Existential Psychology Pre-conferences; how has your experience been with those?

Slowing a moment in time can increase attention to and processing of otherwise brief events, making them more memorable and leading to greater metacognitive integration/coherence, significance, and overall meaning.

Bao Han Tran: This year was actually my first time attending the Existential Preconference in person, and it was such a meaningful experience. I had attended virtually before, but being physically present made it feel much more real and connected. I got to hear talks from scholars I’ve admired and cited for years, and I especially enjoyed the poster session. I met so many people who share overlapping interests in time perception, nostalgia, and relationships. Some of us have already started emailing and brainstorming ideas. I’m hoping to form a collaborative working group on time perception. It felt energizing to meet people who really get excited about the same kinds of questions I’m exploring.

One of the most memorable conversations I had at the conference was about how we psychologically manipulate time to reflect meaning. For example, we often slow down video footage to emphasize important moments. For example, dramatic sports replays or pivotal movie scenes. That slowness signals meaning. Even in wedding photography, there’s a stylistic trend of creating soft, nostalgic images that visually stretch or blur time to capture a feeling rather than just a moment. I’ve started thinking about how we could study this experimentally. What happens if people watch a video that is personally meaningful to them, but it’s slowed down slightly or sped up without them realizing it? Would that affect how meaningful it feels? How might people from different cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds experience time differently in those conditions? These are the kinds of generative questions that come out of a space like the Existential Preconference.

ISSEP: What is one piece of advice you would give to future students who have an interest in following in your footsteps?

Bao Han Tran: I always try to tailor my advice to people who are really anxious, because that's the experience I know best. If you're someone who’s afraid of stepping into something unknown, you're not alone. I live by two quotes: “If you're scared, do it scared,” and “The hardest part is starting.” My undergraduate faculty mentor spoke these words when I was a research assistant, just starting off, and they’ve stuck with me ever since.

Clockwise from top left: Orson Scott Card and the first book in his Ender’s Game series; Trinity River near Dallas, TX.

When I was applying to graduate school, I was surrounded by incredibly smart people and often found myself thinking, “How do I even fit in here?” I had a lot of self-doubt. But I applied anyway. You never know what will resonate or stick. I've had success just putting ideas out there, even when some of them didn’t land or get picked up. You learn by trying. I also have a lot of social anxiety, but I say yes to things as a way to practice. I push through because my ambition is stronger than my fear. It has to be if I want to keep moving forward. So, if you care about something, let that care drive you. Fear doesn’t mean you’re not ready. It just means you’re growing. Keep going, even if it’s scary. Especially if it’s scary.

ISSEP: Can you tell us a little about yourself outside the work/research context?

Bao Han Tran: Outside of research, I enjoy many classic pastimes: reading, making art, listening to music, and spending time with friends. Recently, I finished the first two books of Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game series, which I found both captivating and thought-provoking. They explore what it means to be “human,” who is deserving of compassion, and whether we should respect cultural practices that conflict with our own moral standards. These themes often make me reflect on the current political climate, particularly the persistence of dehumanization and the justification of xenophobia. I’m drawn to books that challenge how I think about these and similar core concepts.

On my daily walks along the Trinity River, I sometimes notice small moments in nature, whether by watching ants or observing the changing seasons, that spark bigger questions about morality, empathy, and our place in the world. In many ways, even outside of research, my mind gravitates toward research-like questions, but in a more personal and reflective way, fueling my curiosity and desire to seek answers.

ISSEP: A lot of us like to listen to music while working, what are you listening to lately?

Bao Han Tran: When I’m working or studying, I usually go for moody, indie, or folk music. Taylor Swift’s Folklore and Evermore are regulars on my playlists, along with Gracie Abrams, and Phoebe Bridgers. They help me slow down and settle into a more reflective state. But if I’m in a time crunch or need to power through a deadline, I switch to chaotic classical music. It’s still piano-driven, but a lot more intense and energizing.

Lately, I’ve also been listening to “Party 4 U” by Charli XCX. I found it through fan edits of couples in movies and books. Those kinds of emotional, time-bending edits are something I absolutely love. I think there’s something really beautiful about how music can shift how we experience time, especially when it’s tied to longing or emotional tension. Other songs that give me a similar feeling are “Ceilings” by Lizzy McAlpine and “Gilded Lily” by Cults. I know these choices date me a little, but I like the idea of looking back and remembering this moment in time.